These Dragonflies Helped an Astronomer Find Ghostly New Galaxies

A Yale scientist set out to capture the insect’s full lifecycle and ended up discovering hidden wonders of the cosmos

As an astrophysicist, Pieter van Dokkum is probably best known for looking at the far edges of the cosmos, where he has discovered new stars and galaxies. But on summer days you are likely to find him standing knee deep in a reedy Connecticut pond, camera at the ready, staring at dragonflies zooming just inches away from his lens.

I’ve known van Dokkum for a few years. He has a wry sense of humor and speaks with the lightly guttural accent of his native Holland. For much of the past decade, he has been coming to this pond outside New Haven, Connecticut, to document its natural wonders. In the dead of winter, we take a walk out to the pond, where he calculates he has spent more than a thousand hours photographing dragonflies. His frequent forays have became so well known among colleagues that early one morning he got a call on his cell phone from Europe as he waited patiently to snap a picture. "You’re standing in the pond, aren’t you?” the caller immediately asked.

Except for the polar regions, dragonflies and their close cousins, damselflies, are found the world over, from deserts to the Himalayas, and of course in many backyards. According to the fossil record, they have been around for some 300 million years and may have been the planet’s first flying animals. At one time they had wingspans of up to two feet. In modern species, the double-pair wings can reach more than seven inches across, allowing them to hoover, swoop, zoom and loop with the dexterity of a helicopter, the acrobatics of a biplane and the speed of a jet.

“They are one of the most successful species around,” says van Dokkum. Yet before he began snapping pictures of them in their many guises and behaviors, nobody had managed to catch the entire dragonfly lifecycle in close-up photography. Fascinated by their aerial displays, their elongated bodies, the bulbous yet oddly humanoid eyes and their gemlike coloration, he set out to make a complete photographic record of their journey through life. The project took him to 50 sites in the United States and Europe, though most of his photography took place around the Connecticut pond. The results are displayed in a forthcoming book, Dragonflies: Magnificent Creatures of Water, Air, and Land (Yale University Press).

“The life cycle of dragonflies is superficially similar to that of butterflies,” explains van Dokkum. They begin life as eggs underwater, then hatch into nymphs that, after a period of feeding, molting and growth, clamber up reeds or other vegetation into the air. Unlike butterflies, the nymphs don’t make a transition through a pupal stage within a cocoon, but exit their shells ready to go through a quick-change metamorphosis into winged adults. A stretch of their new wings, and they’re off in search of food and a mate. “They are ethereal creatures,” van Dokkum says--dragonflies typically live only a few months as adults.

In making a detailed visual record of their behaviors, art and science merged: “You need patience and knowledge to see these events happening,” he says. “I learned over time to predict where and when I would see a particular behavior.” He arrived early before sunrise to capture dewdrops on the gossamer wings of a resting dragonfly, while night visits allowed him to witness the magic of nymphs emerging from the pond and going through metamorphosis in the moonlight.

The book includes photographs of dragonflies making their curious loops that almost always result in snatching unsuspecting prey out of the air. “They are incredibly successful hunters,” he says. Van Dokkum also caught several pairs in the midst of their “mating wheel,” during which their coupled bodies form a ring while flying in tandem. His personal favorites among the 5,500 known dragonfly and damselfly species are the emerald dragonflies, which have exquisitely metallic colors and enormous iridescent green eyes. “They fly continuously,” he says. “They were very difficult to photograph.”

In the astronomy world, van Dokkum works at Yale University, where he specializes in the formation and evolution of galaxies, including our own. Asked why an astronomer who peers out at distant celestial objects would become obsessed with an earthly insect, he says he doesn’t see a contradiction in the two impulses. “I try to capture things you can’t see very well, to make the invisible visible,” he says. “Both use cameras and lenses. And there’s also something beautiful to them; I feel a sense of mystical and emotional connection there.”

The time spent observing dragonflies has actually paid off for van Dokkum’s day job. Dragonfly eyes are composed of 30,000 compound lenses that enable them to spot and capture prey with astounding accuracy. While watching them hunt, it came to him that combining multiple lenses into a single telescopic instrument could reduce light interference and possibly improve his ability to find some of the hardest to see celestial objects.

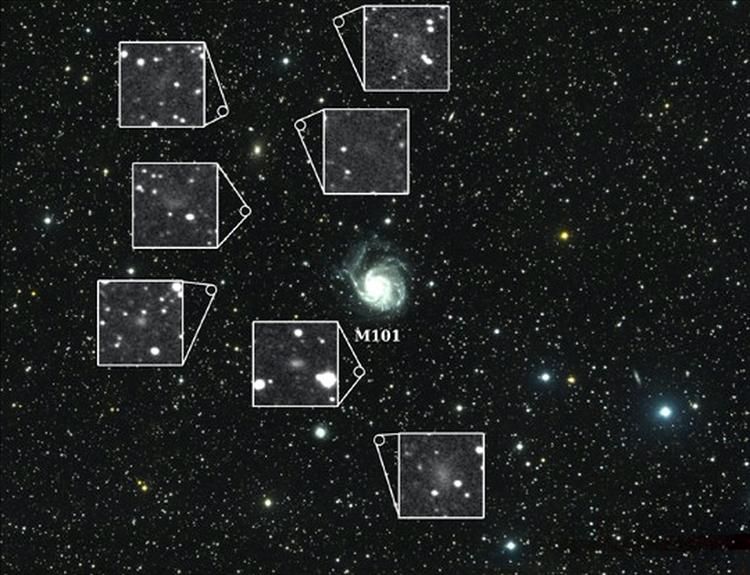

This past summer he and a colleague set up what he named the Dragonfly Telephoto Array in the New Mexico desert. The telescope consists of ten standard telephoto lenses and cameras linked by computer to create a single image. Thanks to the Dragonfly array, he discovered seven previously unseen dwarf galaxies, which may represent an entire new class of galaxies that had been missed even by Hubble. “It’s the same thing of bringing things into focus that had not been seen before,” he says.

During our visit, the pond where van Dokkum took most of his dragonfly photos is frozen and snow covered. But the dragonfly nymphs teeming below the ice will begin to emerge again in the spring and start their dragonfly lives. When they do, he’ll be there waiting, ready to capture the moment.