Piecing Together Eolambia

Paleontologists uncover a new look for one of Cretaceous Utah’s most common dinosaurs, Eolambia

![]()

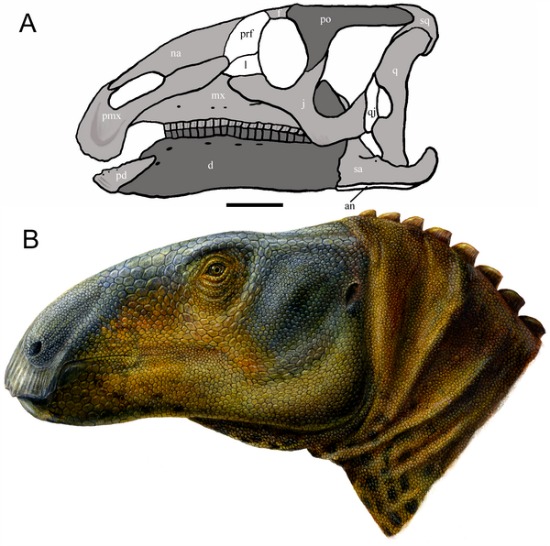

The reconstructed skull of Eolambia–based on a partial adult skull and scaled juvenile elements–and a restoration by artist Lukas Panzarin. From McDonald et al., 2012.

Hadrosaurs were not the most charismatic dinosaurs. Some, such as Parasaurolophus and Lambeosaurus, had ornate, hollow crests jutting through their skulls, but, otherwise, these herbivorous dinosaurs seem rather drab next to their contemporaries. They lacked the garish displays of horns and armor seen among lineages such as the ceratopsians and ankylosaurs, and they cannot compete with the celebrity of the feathery carnivores that preyed upon them. Yet in the habitats where they lived, hadrosaurs were among the most common dinosaurs and essential parts of their ecosystems. What would tyrannosaurs do without ample hadrosaurian prey?

While many hadrosaurs might seem visually unremarkable next to their neighbors, the wealth of these dinosaurs that paleontologists have uncovered represent a huge database of paleobiological information waiting to be tapped for new insights into dino biology and evolution.

In order to draw out dinosaur secrets, though, paleontologists need to properly identify, describe and categorize the fossils they find. We need to know who’s who before their stories can come into focus. On that score, paleontologist Andrew McDonald and colleagues have just published a detailed catalog of Eolambia caroljonesa, an archaic hadrosaur that was once abundant in Cretaceous Utah.

Eolambia is not a new dinosaur. Discovered in the roughly 96-million-year-old rock of the Cedar Mountain Formation, this dinosaur was named by paleontologist James Kirkland–a coauthor on the new paper–in 1998. Now there are multiple skeletons from two different localities representing both sub-adult and adult animals, and those specimens form the basis of the full description.

While the new paper is primarily concerned with the details of the dinosaur’s skeleton, including a provisional skull reconstruction accompanied by an excellent restoration by artist Lukas Panzarin, McDonald and coauthors found a new place for Eolambia in the hadrosaur family tree. When Kirkland announced the dinosaur, he named it Eolambia because it seemed to be at the dawn (“eo”) of the crested lambeosaurine lineage of hadrosaurs. But in the new paper McDonald, Kirkland and collaborators found that Eolambia was actually a more archaic animal–a hadrosauroid that falls outside the hadrosaurid lineage containing the crested forms.

Much like its later relatives, Eolambia would have been a common sight on the mid-Cretaceous landscape. The descriptive paper lists eight isolated animals and two bonebeds containing a total of 16 additional individuals. They lived in an assemblage that was right at the transition between the early and late Cretaceous faunas–tyrannosaurs, deinonychosaurs and ceratopsians have been found in the same part of the formation, as well as Jurassic holdouts like sauropods. How this community fit into the grander scheme of dinosaur evolution in North America is still coming together, though. The Early and Middle parts of the Cretaceous are still poorly known, and paleontologists are just getting acquainted with Eolambia, its kin and contemporaries.

References:

McDonald, A., Bird, J., Kirkland, J., Dodson, P. 2012. Osteology of the basal hadrosauroid Eolambia caroljonesa (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah. PLOS One 7, 10: e45712

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)