Playing Music as a Child Leads to Better Listening as an Adult

A new study indicates that musical instruction for just a few years during childhood can have long-lasting benefits

![]()

A new study indicates that musical instruction for just a few years during childhood can have long-lasting benefits. Photo by Brian Ambrozy

In the fourth grade, at age 9, I joined the school band and started playing the trombone. At the end of sixth grade, at age 12, I quit.

Over the past few years, an inventive team of neuroscientists at Northwestern University has conducted a number of studies that show playing music confers a remarkable range of benefits on the brain—musicians show an increased ability to pick out a speaker’s words in a noisy environment, are better at detecting emotion in speech and stay sharper at processing sounds as they age. All this time, I assumed that I’d stopped far too quickly to experience any of these benefits.

New research, though, should give drop-outs like me hope. According to a study published today in the Journal of Neuroscience, the same researchers found that just one to five years of experience playing music as a child was associated with an improved cognitive ability in processing complex sounds as a young adult.

“We help address a question on every parent’s mind: ‘Will my child benefit if she plays music for a short while but then quits training?’” says Nina Kraus, the study’s co-author. “Based on what we already know about the ways that music helps shape the brain, the study suggests that short-term music lessons may enhance lifelong listening and learning.”

Most previous neurological research on the effects of musical training on the brain has focused on the rare individuals who start off playing music as children and keep at it, continuing through college or even becoming professional musicians. But the vast majority of us stop well before that. After numerous studies looking at the former category, Kraus’ team decided to turn their attention to the latter, to see if the same effects could be found.

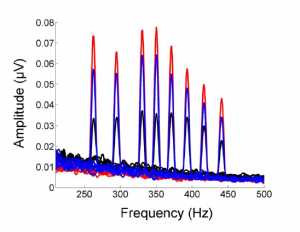

For the study, the research team put to use the same techniques they pioneered in their earlier work: exposing individuals to different musical sounds and carefully measuring the electrical signals emitted by their auditory brainstems with electrodes mounted on the scalp. As they’ve previously found, our brain signals mirror the actual sound waves we hear, so by observing different participants’ signals, they can determine how skilled each person is at hearing and mentally interpreting the sounds.

They split 45 adult participants up into three groups—those with no musical instruction, those with one to five years of instruction and those with six to 11 years of instruction. For both of the groups with experience, the average age at which they started playing an instrument was roughly nine years old, as is typical in American public schools. They then put each of the participants in a soundproof booth, had them put on a pair of headphones, played them a series of complex sounds (made up of multiple tones) and measured the signals emitted by their auditory brainstems.

Musicians with more than six years experience (red) showed the greatest mental response to the tones, but those with one to five years (blue) still did better than those with none (black). Image via Northwestern University/Nina Kraus

The results were striking. Although the signals detected from the most experienced musicians showed the most robust response to the sounds, the participants with just one to five years of experience still showed significantly greater cognitive ability in processing them as compared to the group with no experience. The researchers say that this mental response indicates the ability to pull out the lowest frequency in a complex sound, and their previous work has shown this ability is crucial for both speech and music perception, especially in noisy environments. Thus, playing music for just a few years as a child seems to be linked with better listening skills much later on.

Kraus says that the findings are relevant to public education policies, especially given that funding for music education nationwide is declining rapidly in the face of budget cuts (for example, in 2011, nearly half of California school districts cut or reduced art and music programs). “Our research captures a much larger section of the population, with implications for educational policy makers,” she says. “ earlier research, we infer that a few years of music lessons also confer advantages in how one perceives and attends to sounds in everyday communication situations, such as noisy restaurants.”

They results are also quite relevant, presumably, to parents. If your kids hate playing in the school band, it’s okay to let them quit. The benefits will still be there when they’re grown upas long as they’ve played for a year or two.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)