Pluto May Have Ice Volcanoes at the Bottom of Its Heart

Two southern peaks have depressions that hint they once spewed icy slurry onto the tiny world’s surface

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/8f/188f9b2b-17d3-4a83-b6ff-a7a74dd47973/nh-pluto_crop.jpg)

Colorful, craggy and decorated with a heart, Pluto has been flaunting its weirdness since it first came into focus in July. Now planetary scientists can add ice volcanoes to the tiny world's growing list of unexpected quirks.

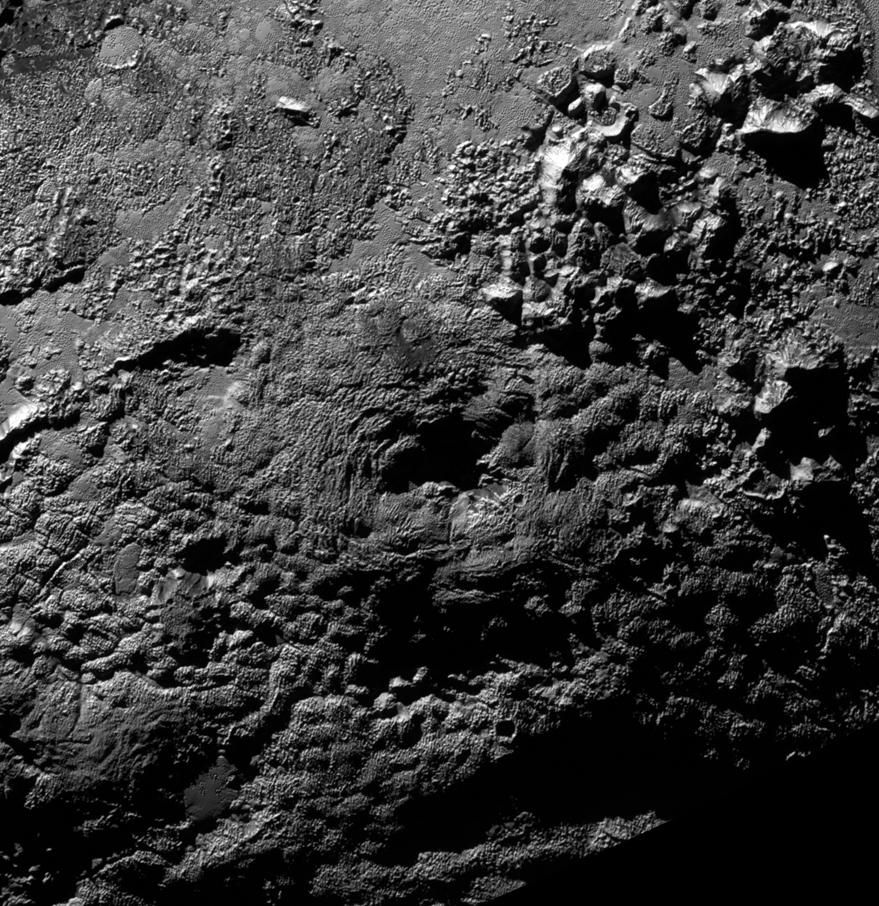

Two mountains near the southern edge of the heart-shaped plains on Pluto appear to be volcanoes that once spewed a slurry of ices onto the surface. These so-called cryovolcanoes support the notion that cold, tiny Pluto is a far more active world than previously thought.

One icy peak, informally named Wright Mons, stands about two miles high. The other, Piccard Mons, is 3.5 miles high. Both are about 100 miles wide and have definite depressions at their tops. According to the team, the formations look a lot like shield volcanoes, akin to the Hawaiian island chain on Earth and Olympus Mons on Mars.

"We see nothing of this scale with a summit depression anywhere else in the outer solar system," Oliver White, a scientist with NASA's Ames Research Center in California, said today during a press briefing. "Whatever they are, they are definitely weird, and volcanoes may be the least weird hypothesis at the moment."

The finding comes from the New Horizons mission to Pluto, which conducted a flyby of the distant world in July. The probe gathered a wealth of data as it zoomed past Pluto, and not all of the information has even made it back to Earth. While the images in hand allowed the team to build 3D maps of Pluto's topography and spot the volcanoes, it's still unclear when these features might have been active and what would have driven their eruptions.

According to White, the team was fortunate to even see Piccard Mons because it sits in the twilight zone, near the day-night border in the New Horizons maps. Without enough of an atmosphere to scatter some light, the dim peak may have gone unnoticed. As it stands, Piccard is a harder mountain for teasing out details.

Mission scientists got a better view of Wright Mons, and they can see some light cratering on its slopes. That at least tells them that the volcanoes are somewhat older than the nearby craterless terrain of Sputnik Planum, the western lobe of the heart feature, which suggests it's been a while since the volcanoes were active.

Since Pluto is relatively small, heat from its initial formation must have vanished quickly. Instead, the team thinks that some radioactive material inside Pluto probably provided the heat needed to drive eruptions. You would not need much, says White--the known ices on Pluto are relatively volatile, and it would not take anywhere near as much energy to get them oozing out of a cryovolcano as we need to drive eruptions of molten rock on Earth.

He adds that finding two volcanoes together suggests that this region may have once hosted a volcanic plain, and more icy peaks may be lurking in the dark of Pluto's night side.

The cryovolcanoes are arguably the coolest revelation in a parade of Pluto results being presented this week at the American Astronomical Society's Division of Planetary Sciences meeting in Maryland.

"It's been four months past the flyby, and we can tell you that New Horizons gets an 'A' for exploration," says project leader Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute. "But I also think we get a couple 'Fs', and one of those is for predictability--Pluto is baffling us."

In addition to the possible volcanoes, the topography maps revealed tall scarps and other so-called expansion features--signs that Pluto may have a subsurface ocean of water that is expanding as it freezes. Other data from New Horizons show that Pluto's atmosphere is much more compact than previously thought, and that it is being stripped away by solar radiation at a rate thousands of times slower than predicted.

Also, studies of Pluto's small moons--Styx, Nix, Kerberos and Hydra--show that they are tilted on their sides and are spinning at wildly faster rates than thought. Hydra, the outermost moon, rotates so fast that a day lasts just 10 hours, and the other moons are not far behind. This dizzying dance is bizarre, because while impacts could have set these small moons spinning, gravitational tugs from Pluto and Charon should slow them down over time.

"We predicted that this system is chaotic," says Mark Showalter, a New Horizons team member at the SETI Institute. "I would describe this system not as chaos but pandemonium."

Now that New Horizons has sped past Pluto, mission members are making preparations for an encounter with another object out in the Kuiper belt. Dubbed 2014 MU69, this small body is thought to be a pristine relic from the birth of our solar system, a raw planetary building block that formed in the cloud of dust and gas leftover from the sun's birth.

The mission team has already pointed the spacecraft at 2014 MU69 and is waiting for news on whether they will have enough funding from NASA to continue the mission. In the meantime, they will continue to analyze the information that is still raining down from the spacecraft and present findings that will no doubt spark hearty debates among planetary scientists.

"New Horizons has put on quite the show for us, starting with the close encounter back in July," says Curt Niebur of NASA headquarters. "Today marks another exciting milestone: It marks the beginning of the process for figuring out what all this wonderful data means in the grand scheme of things."