Pop-Up Relief in Kenya’s Slums

Solar-powered huts built by a Montana-based construction company provide two big needs: water and cellphone power

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/HabiHut-Kenya-water-electricity-631.jpg)

Goats were grazing on a patch of grass littered with plastic garbage when Phylis Mueni passed by. She carried three 20-liter jerrycans that once held vegetable oil, one a bright yellow that matched her oversize T-shirt. Everything else was a wash of browns and reds—the rusted metal of corrugated roofing, the labyrinth of mud houses, the drainage ditch that ran along the gullied path. Mueni is a resident of Korogocho (which means “shoulder-to-shoulder” in Swahili) one of Nairobi’s largest and roughest slums. She was in pursuit of a most basic element: water. No one in places like this has running water. On a good day, locals travel 300 feet to fill up their cans for a few cents. On shortage days, which happen about once a week, the search can take most of the day, and people can end up paying six times the usual price.

Mueni entered a schoolyard through a door banged out of sheet metal and painted yellow that read Kao La Tumaini (Place of Hope.) Inside, most of the small courtyard was taken over by a recent addition to the school, a structure that stood in stark contrast to its surroundings. Made of smooth, white plastic panels and metal, the hexagonal HabiHut water station jutted into the sky at a sharp angle, a solar panel and a single light fixture at its peak and water taps at its base. Fitted with a water tank and filtration system, as well as the solar panels and batteries for cellphone charging, these stations have the potential to serve up to 1,000 people per day. For poor Kenyans, mobile phones have rapidly become a powerful information tool linking them to employment, financial networks and security data. In a country where 40 percent of the population doesn't have access to safe water and only 20 percent has access to grid electricity, kiosks like these are, indeed, a place of hope.

The project is part of a pilot program that brings together Kenyan government and nonprofit organizations, local entrepreneurs and community groups, and American companies large and small. HabiHut is a tiny Montana-based company that emerged from the ashes of a high-end contracting business that went bust in the housing crash. The company created the HabiHut modular kit, and along with local Kenyan nonprofit Umande Trust, is in the process of teaming up with General Electric, which is providing water filtration and solar panel and battery systems as the pilot project expands throughout Kenya. Plans are underway to set up 200 more kiosks, each providing up to 1,600 gallons of clean water per day. If everything goes well, they hope to replicate the model in places like India and Southeast Asia.

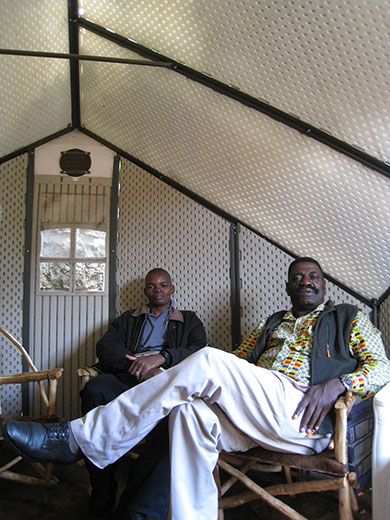

Kenya needed something almost improvisational to get water to people like Phylis Mueni, , and the HabiHut’s mobility and impermeability fit the bill. The structures were initially introduced to Kenya and Haiti as emergency housing; Umande recognized that the huts could be adapted into water stations. “For a permanent water kiosk, you need to get a city permit from the authority,” said Josiah Omotto, managing trustee of Umande. After a long application process, “still nothing happens after months. And you have to use their standard design,” he told me as we sat in his office in Kibera, another massive Nairobi slum, meaning there’s little room for experimentation and improvement. “Let’s be out of this cycle,” he said.

Because HabiHuts are considered impermanent, they dodge Kenyan building regulations. And they’re quick. The modular structures arrive in a four-foot-by-eight-foot package and pop up in a day. When the program is fully implemented, the water can come from either the city system or delivery trucks drawing on a nearby natural source such as a river, and the filters will remove bacterial, viral and protozoal pathogens that are responsible for typhoid, cholera and other water-borne diseases that ravage slum residents. And if a source of water becomes tenuous, which can happen when city pipes break or the mafia-like entities that have their tentacles around water distribution demand bribes or cut off water to create artificial demand, the HabiHuts can be relocated to a more dependable spot. It's like guerrilla warfare for water.

Not that the program is renegade. It attempts to merge a business model with creative engineering to solve the widespread problem of water shortages. The idea is that Umande will cultivate local entrepreneurs and community groups to run the water kiosks for a profit, selling water, cellphone charging services and phone cards. Ronald Omyonga, an architect and consultant on the project, is busy touring the country in search of potential partners that have the ability to invest a small portion of the start-up costs to show their commitment.

As other locals joined Mueni at the Korogocho HabiHut, setting their containers on a simple wooden platform, Kelvin Bai, Umande’s water specialist, stood nearby smiling. “To me, growing up,” he said, “water was the major issue.” He lived in Kibera, where his mother would sometimes walk up to three miles to get water for the family. “When I came of age, I was sent out in search of water too.”

Abdi Mohammed is chairman of the Mwamko Wa Maendeleo Youth Group, which operates the Korogocho site. This area “is a black spot, with a lot of violence,” he said. “It is known for muggings, in broad daylight.” He looked up at the single light on the HabiHut. “That light on the HabiHut is very, very helpful. It is the only one in this area. We find hope in things like this.”

Cellphones are not quite as vital as water, but getting close. In just five years, the number of mobiles went from 1 million to 6.5 million in Kenya, and the East African nation is at the vanguard of using mobile telephony for finance and information technology among the poorest of the poor. Kenyans use mobile phones to secure micro-insurance for their agricultural crops, track the spread of violence during times of civil unrest, and earn income in a country with a 40 percent unemployment rate, using a text-based model akin to Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, which links companies to individuals who can do small tasks for a fee. Kenya is also one of the first nations in the world to implement a comprehensive mobile banking system known as M-Pesa, in which people can pay for everything from bus rides to utility bills to—yes—water at their local HabiHut kiosk with their phones. Umande is also working with Stanford University to create a mobile crowd-sourcing system so settlement residents can easily locate clean, cheap water on shortage days. When people use their phones for such basic services, ensuring that they’re charged becomes crucial.

Inside the HabiHut, a young man from the youth group basked in a warm glow of light coming through the translucent panels. He worked a hand pump on the inside and leaned his head out to make sure the liquid gold was flowing. It poured out in a thick stream into Mueni’s waiting container. Before this kiosk was here, Mueni had to go “Mbali!”—far!—she said, waving her hand over her head in the direction of the next closest traditional water station, which was a third of a mile away. Now, she comes to this little place of hope.

Meera Subramanian wrote about peregrine falcons in New York for Smithsonian.com.