Popular Pesticides Linked to Drops in Bird Populations

This is the latest in a string of studies suggesting that some pesticides impact birds as well as pollinators

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/0e/d00e244c-a42b-42ce-b7be-0647d2ab8eca/spreeuwimg_984222_altenburgedit.jpg)

Let me tell you about the birds and the bees: A family of pesticides called neonicotinoids has been linked with pollinator declines. While their involvement in bee colony collapse is hotly debated, ecologists are wondering: could neonicotinoids impact something further up the food chain?

A study published yesterday in Nature suggests that birds and bees may share a common enemy. Dutch researchers have found a correlation between bird population declines in the Netherlands and higher concentrations of the common neonicotinoid pesticide imidacloprid in surface water.

“There is an alarming trend between declines of local bird populations and imidacloprid in the environment, which needs serious attention to see what we want to do with this pesticide in the future,” says Hans de Kroon, a co-author and plant ecologist at Radboud University in the Netherlands. The researchers posit that the pesticide affects these birds by killing off their bug food supply.

Concerns have been raised about neonicotinoids’ affect on bees since the chemical first emerged on the pesticide scene in the 1990s. What makes them popular is the fact that they’re supposed to only harm insect pests keen to munch on plant leaves. In insects, the pesticide binds to specific receptors in the nervous system, ultimately killing the insect.

Because the chemical has a lower binding affinity to the same type of receptor in mammals, birds, and other larger animals, it’s also supposed to be less toxic and thus less dangerous to those species.

However, neonictoninoids’ harmless reputation is beginning to erode, as studies point to the pesticides having unintended consequences on pollinators, other insects and even some wildlife. For example, a 2013 study associated higher concentrations of neonicotinoids in polluted water to overall insect population drops in the Netherlands—not just drops in those that munch on or pollinate crops. While crops absorb some of the pesticide, the rest can seep into water and soil, where it can linger for almost three years before degrading. It’s here that unintended targets can pick up the pesticide, causing a wider population of insects die.

Given that overall populations of bugs show declines and farmland birds have been disappearing across Europe, de Kroon and his colleagues began to think more broadly. “Many species depend on insects during the breeding season for raising their offspring and for their own wellbeing,” says Caspar Hallmann, another co-author and plant ecologist at Radboud University. “So, if insects fall away from an environment then what about our birds?”

Across the Netherlands, the researchers selected common 15 farmland bird species, including the barn swallow (Hirundo rustica) and the common starling (Sturnus vulgaris), all of which rely on insects as either their sole or primary food source. Thanks to an extensive data set kept by the Dutch Common Breeding Bird Monitoring Scheme, they were able to track the rise and fall of populations across the Netherlands from 2003 to 2010. Surface water quality measurements gave the researchers concentration data for imidacloprid from 2003 to 2009 in canals and waterways across the country. Mapping one data set against the other, they looked for patterns.

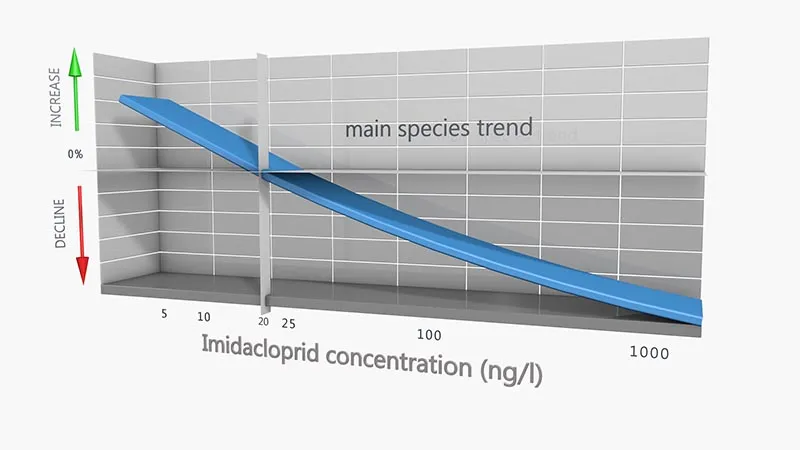

In areas with imidacloprid concentrations higher than 19.43 nanograms per liter, bird populations were in decline. The average rate of decline was 3.5 percent annually—that makes for more than a 30 percent decline over 10 years, notes de Kroon. The higher the imidacloprid concentration the more severely the bird populations dropped.

Pesticide use is hardly the only factor that could influence bird population health—habitat loss, bulb agriculture, greenhouses and other land use trends could all impact insect communities. So, the authors compared trends in those factors, too, but none matched up with population patterns as well as variation in pesticide concentration. “Locally some populations increase, some decline,” says Hallmann. “Imidacloprid [concentration] is by far the best explanatory variable for these trends.”

Just how, then, does the pesticide affect birds? The researchers hypothesize that the mechanism of this effect is through the food chain. Previous studies have shown that a significant blow to birds’ prey can send a population spiraling. “Food levels determine population size of insectivores but also their body condition, breeding success, etc,” says Brigitte Poulin, an ecologist at Tour de Valat Research Center in France unaffiliated with this study. So rather than killing the birds directly, the toxin can work indirectly to malnourish birds.

But birds also might encounter neonicotinoids directly—catching an accidental spraying, eating a pesticide-covered seed, or even accumulating the toxin by eating pesticide laced insects (there’s no field evidence to support this, though). Some insect-eating birds also supplement their diets with seeds outside of breeding season, and a handful of studies have shown that eating seeds doused in neonicotinoids proved lethal to some birds after only a few days. Seeds treated with imidicloprid and other neonicotinoids are commonly used—not just in agriculture and but also in backyard gardening. And birds that drink nectar, such as hummingbirds, may face even different sets of risks and unknowns.

Though this study is the first to link bird population trends to neonicotinoid concentrations, it’s not the first to look beyond bees to birds. Last month, the Task Force on Systemic Pesticides, an international team of scientists convened by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, published a report citing growing evidence of neonicotinoid’s harmful effects on birds, as well as other vertebrates such as fish and lizards.

This might all sound a bit familiar: a promising, popular pesticide kills insects with reverberations through local food webs that ultimately lead to the decline of birds. In the 1960s, ecologists noticed that though dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) was a great mosquito-killer, it had cascading effects on bald eagles and even humans. “We now have a new insecticide that we thought was doing everything right and it appears that it's not—and that is a little bit of repeated history,” de Kroon reflects.

So, are neonicotinoids the new DDT? Yes and no. DDT impacted species through bioaccumulation and by mimicking estrogen, causing cancer. At the moment, there’s no evidence to suggest that either is at play with neonicotinoids.

Nevertheless, it’s a comparison ecologists favor, and neonicotinoids clearly have much more widespread affects on ecosystems than expected, as Dave Goulson, an ecologist at the University of Sussex points out in an editorial in Nature this week. Silent Spring author Rachel Carson “would undoubtedly think that we seem to have learnt little from our past mistakes,” Goulson writes.

Ecologists hope that the mounting evidence against neonicotinoids can spur regulatory action. To better assess environmental impacts, the EU has already instituted a two-year ban on the pesticides, which went into effect in December. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is reexamining neonicotinoids’ environmental impact at the moment and faces exceeding pressure from environmental groups to take them off the market.

Nevertheless, Bayer CropScience, the primarily manufacturer of imidacloprid, was quick to release a statement yesterday pointing out that the research shows a only correlation, rather than proving a “causal link,” between pesticide use and bird population declines. “Neonicotinoids have gone through an extensive risk assessment which has shown that they are safe to the environment when used responsibly according to the label instructions,” the company maintains.

The evidence may be circumstantial, but the Dutch team’s next step will be to pin down exactly how pesticides could be driving these bird trends to get some solid leads in this environmental whodunit.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)