Powerful Solar Flare Paints the Sky With Candy-Colored Auroras

Two back-to-back flares sent clouds of charged particles racing toward Earth, creating auroras that may last through the weekend

Earth just got smacked by the sun—which means it’s a great time to grab your camera. A solar flare that erupted on Tuesday sparked vivid auroral displays on Thursday night for people in northern sites, including Canada, Alaska and Scandinavia. But an even more powerful flare came on its heels, and it is expected to trigger some supercharged auroras this weekend, possibly painting the skies in lower latitudes.

A solar flare is a burst of radiation triggered by the release of magnetic energy from the sun’s upper atmosphere, or corona. Flares are usually linked to dark blemishes on the solar surface called sunspots, which are also driven by magnetic activity.

“The flares usually come from regions where strong magnetic fields have emerged from inside the sun,” says Leon Golub, a scientist with NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) space telescope and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Massachusetts. “Sunspots are formed that way too, so the two things tend to occur together.”

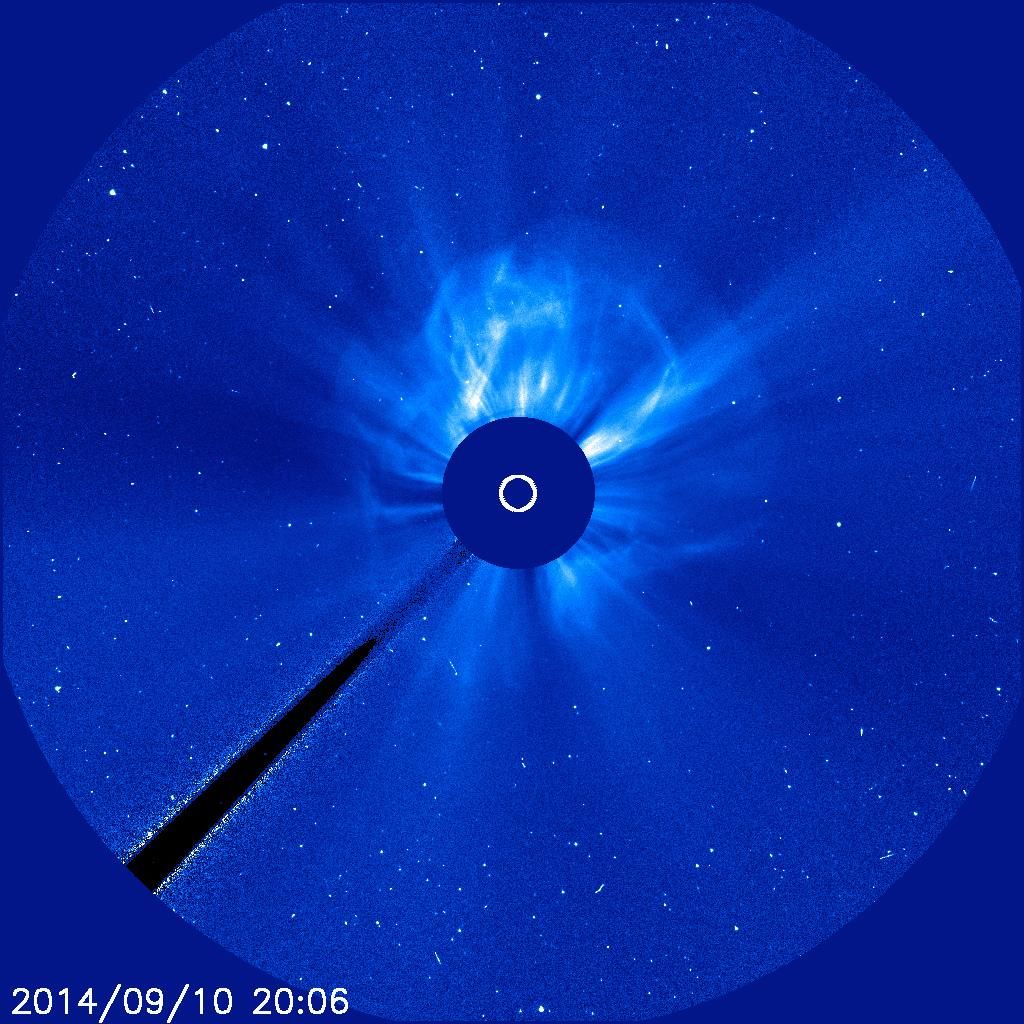

On September 9 and 10, a gaggle of sunspots dubbed Active Region 2158 was aimed toward Earth when the region launched solar flares. This composite video from SDO shows the second burst in multiple wavelengths, which reveal what the sun looks like at different temperature ranges. This helps scientists see what’s happening on the sun’s surface and in the multiple layers of its atmosphere, so they can better understand what drives activity such as flares.

While the Tuesday flare was moderate, the Wednesday event was an X-class solar flare, the most powerful kind. According to Golub, these strong flares almost always trigger coronal mass ejections (CMEs)—clouds of ionized matter hurled from the sun’s corona. When aimed at Earth, a CME can funnel an influx of charged particles along our planet’s magnetic field lines. These particles then interact with molecules in our atmosphere to create multihued auroras. But they can also trigger geomagnetic storms around Earth that can disrupt satellites, jam radio communications and potentially damage the power grid.

Once released from the sun, a CME can take a couple days to reach Earth. Data from sun-monitoring satellites like SDO are helping researchers forecast such solar activity and any resulting geomagnetic storms, so that we can hopefully guard against the worst impacts.

“Our goal is to predict these events in advance and to know which ones will be damaging,” says Golub. “We're closing in on that, and every one we observe brings us closer.”