The Prehistoric Buzz Shark Has a Modern-Day Hero in Artist Ray Troll

How an Alaska-based artist helped solve a mystery that baffled paleontologists for over a century

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/be/43/be4369d4-e496-45d2-a09e-40fbeb0e8939/staab_sculpture.jpg)

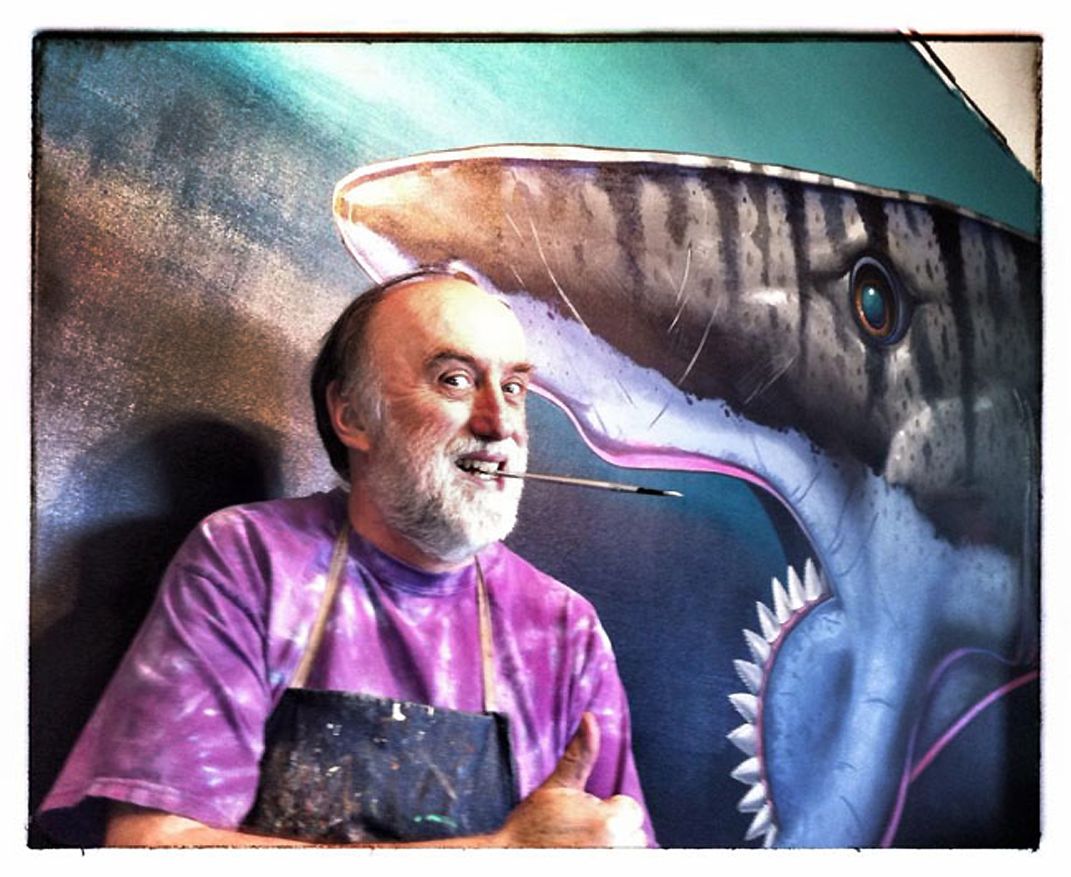

Paleo-artist Ray Troll’s obsession began way back in 1993, when he spotted what he calls a “strange doorstop” in the basement of the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum. “It was a beautiful whorl… I thought it was a big snail,” he says now, recollecting the moment when he visited the museum for a book he was working on.

In reality, his guide explained, the fossilized spiral was the jaw of an ancient shark.

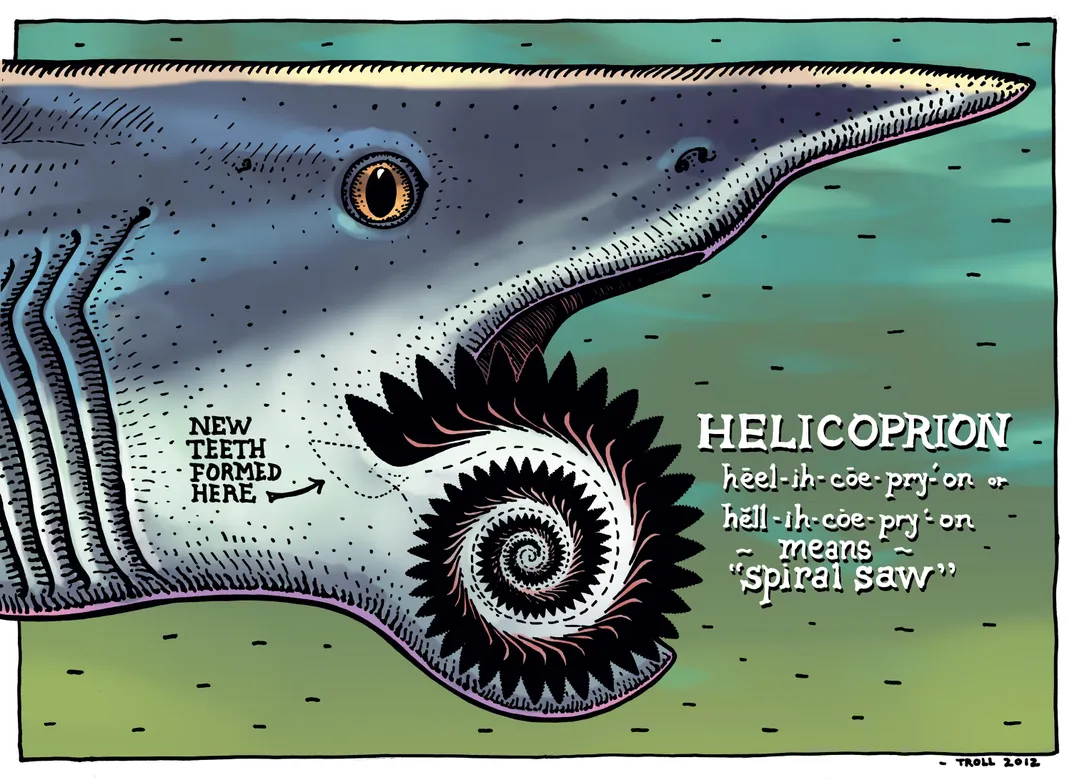

Little did Troll know, this rocky jaw would consume his mind over the next 20 years, just as it had done with scientists before him. The strange tooth “whorl” belonged to the Helicoprion genus, the “buzz sharks” (a moniker Troll introduced in 2012). The bizarre beasts swam Earth’s waters some 270 million years ago, persisting for about 10 million years.

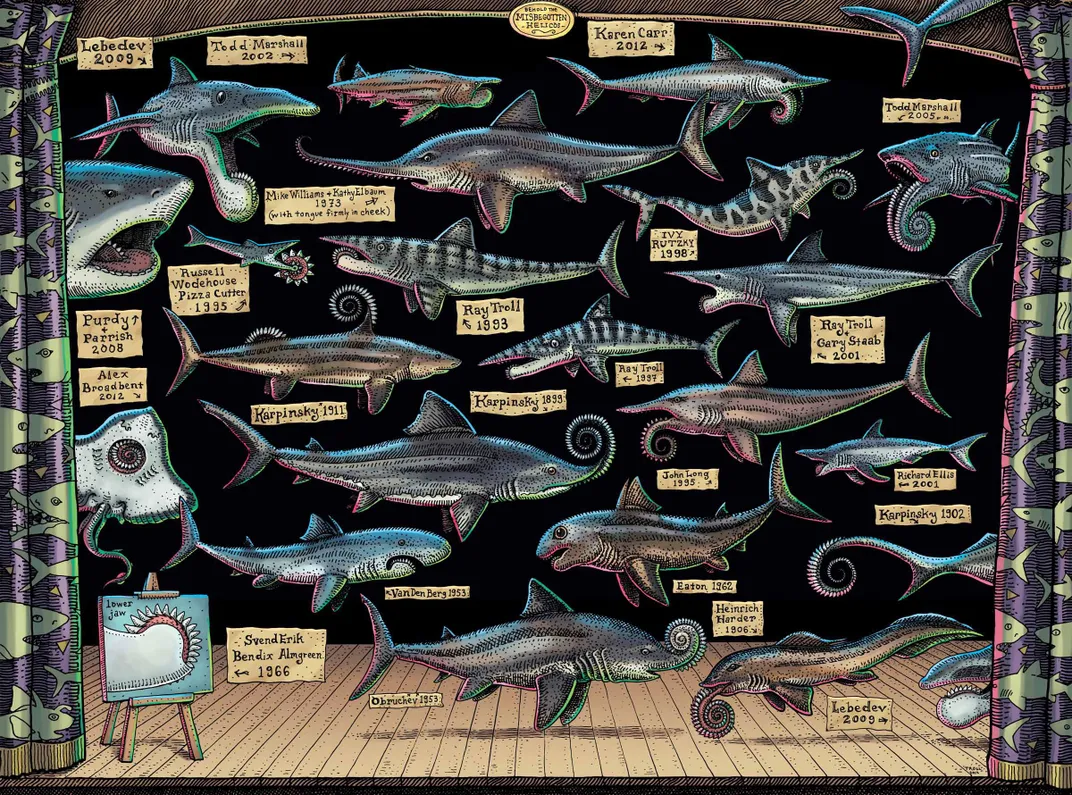

Russian geologist Alexander Karpinsky discovered the first Helicoprion in 1899 in Russia—he imagined the whorl as a fused-together coil of teeth that curled up over the shark’s snout. Throughout the early 1900s an American geologist, Charles Rochester Eastman, made the case that it was instead a defense structure on the creature’s back.

Since these early postulations, no one has been able to perfectly position the more than two-foot-wide spiral of knife-like tips. Smithsonian scientists were even pretty sure that the whorl belonged deep in the shark’s throat. The thought of this century-old fossil enigma was too alluring for the artist to ignore—instantly, Troll was hooked.

About a week after his museum visit, he cold-called the world’s authority at the time on Paleozoic sharks, Rainer Zangerl. Sporting an MFA in studio arts from Washington State University, Troll, now 61, most likely seemed a poor candidate for interpreting paleontological discoveries. But since his first sketch of a dinosaur (“crayons were my first medium”), Troll has demonstrated an irresistible affinity for the extinct and the living, particularly fish.

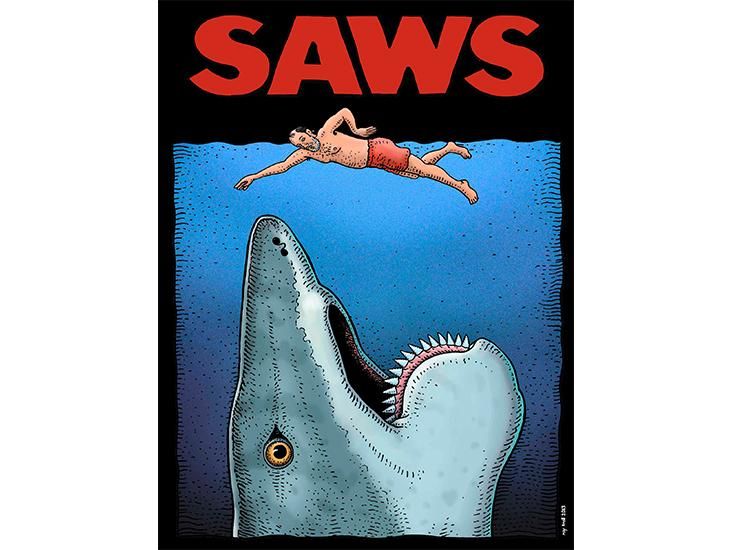

Starting in the 1970s, he began blending his own flavor of surrealism with humor and biology. One 1984 drawing depicts a cluster of fish nearly nipping a bare-bunned human from below. The caption reads: “Bottom Fish.” Another piece portrays two golden orange fish hovering above the ocean, staring at each other in the moonlight: “Snappers In Love.” Perhaps the most popular design, “Spawn Til You Die”, pictures two belly-up salmon and crossbones.

By 1995, his first major touring museum exhibit—“Dancing to the Fossil Record”—was working its way across the country, featuring drawings, fish tanks, fossils and a soundtrack and dance floor. “I just made a career out of shedding light on these animals,” Troll says.

When Troll met with Zangerl, the scientist was “very patient and he mentored me,” Troll recalls. Zangerl introduced him to all sorts of ancient shark species and directed Troll to another expert: Danish scientist Svend Erik Bendix-Almgreen, who had studied Helicoprion extensively and hypothesized decades earlier that the whorl belonged along the beast’s bottom jaw.

Throughout the late ’90s and into the 21st century, Troll’s drawings slowly shifted from a diversity of salmon, snappers and rockfish (printed in magazines, books, t-shirts and as murals commissioned by NOAA and California’s Monterey Bay Aquarium) to a lot of sharks in both natural and surreal settings. “My interest in Paleozoic sharks was at a peak,” he says.

The first time Troll put a Helicoprion to paper was for a book he was working on called Planet Ocean. Thanks to his newfound shark knowledge from “The Helicoprion Masters,” as he refers to Zangerl and Almgreen, Troll became the first person to draw a believable buzz shark. His depiction led to his 1998 appearance on the Discovery Channel’s “Prehistoric Sharks” segment featuring paleontologist Richard Lund.

Troll kept in touch with Almgreen for reference help and by 2001 he was publishing a kid’s alphabet book, Sharkabet, which also turned into a traveling exhibit. It featured a full swath of drawings of the beasts past and present. Helicoprion, of course, was in all of its circular-saw glory, pursuing a thin fish and accompanying the letter “H.”

By 2007, Troll had moved on to fantastical map making with his book Cruisin’ The Fossil Freeway (also a touring exhibit) with author Kirk Johnson, currently the director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Recounting and mapping their 5,000-mile road trip, the book strings together the layered fossil history of the American West and within it, the “ever-elusive fossilized tooth whorls of Helicoprion,” paleo-blogger (and Smithsonian.com contributor) Brian Switek wrote in his review of the book.

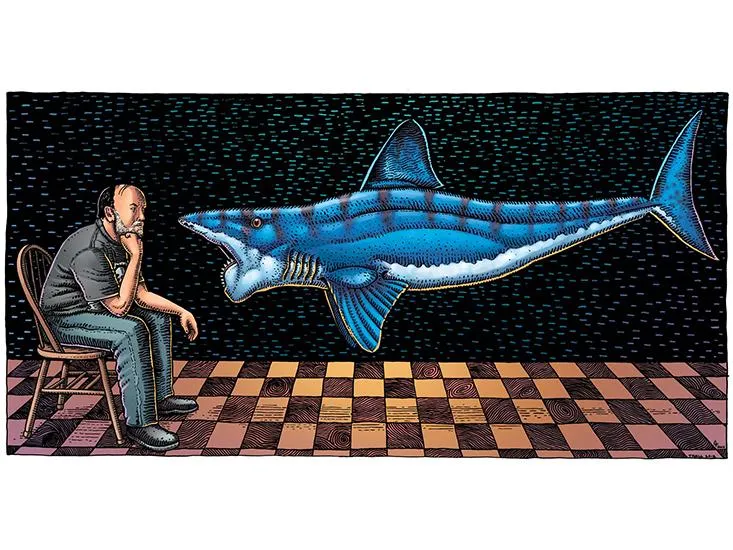

Sure, “there’s a whole host of beasties and creatures that I’m enamored with,” Trolls says: “but Helicoprion became one of my favorite characters in the story of my life.”

Twenty years after his introduction to the fossil, Troll has reviewed the “literally hundreds of drawings” of Helicoprion and turned them into a traveling exhibit of his madness. The show began in 2013 in Idaho, a state rich with Helicoprion fossils, as these sharks once swam in the Paleozoic ocean waters that covered much of the Northern Hemisphere.

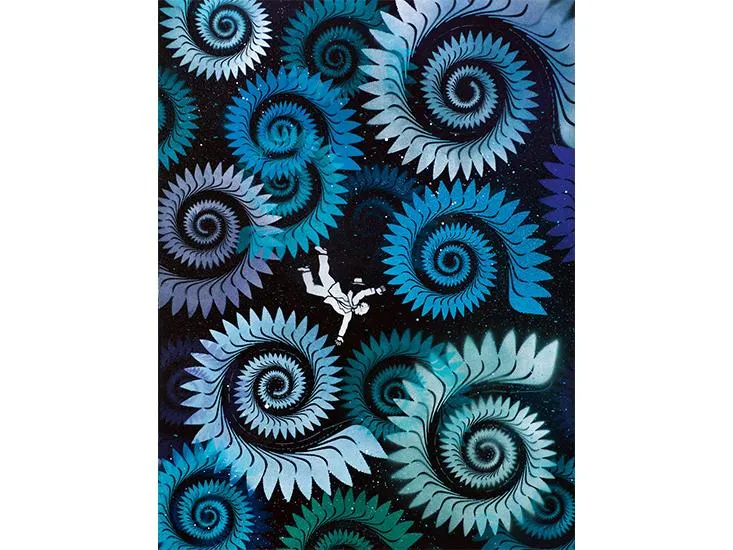

“Unraveling the Mystery of the Buzz Sharks of Idaho” became “The Summer of Sharks” in Alaska and “The Buzz Sharks of Long Ago” in Washington. Its current home lies within the Museum of Natural and Cultural History on the University of Oregon’s campus. The exhibit touts jaw replicas and Troll’s own whimsical whorl depictions, like big yellow spirals that resemble tribal symbols of the sun with scribbled numbers above each tooth. Up to 180 teeth can exist in one whorl, Troll says. His more recent pieces depict a single human silhouette, himself no doubt, tumbling through a skyful of multicolored whorls.

Troll’s passion, however, has served a purpose far beyond the aesthetic charm of a framed picture—it has shaped the scientific community’s knowledge of Helicoprion itself. Back in the mid-1990s, when he wrote and spoke with Almgreen, Troll discovered that the scientist had published his hypothesis about the buzz shark’s physiology in an obscure paper in 1966. This knowledge remained hidden, lost to memory even to prominent paleontologists, until 2010, when an undergraduate student working as an intern at the Idaho Museum of Natural History got in touch with Troll.

Jesse Pruitt had come across the museum’s Helicoprion collection during an introductory tour, and he recognized the fossil from a “Shark Week” episode that had aired on the Discovery Channel a few months before. He asked the collections manager about the whorls. She recalled that Troll had loaned a couple out from the museum for an exhibit “and suggested that I should contact him,” Pruitt says. Right away, “[Troll] told me to find the Almgreen paper and look for Idaho #4, the name of a fossil in the museum’s collections.” At this point, Pruitt’s advisor paleontologist Leif Tapanila became interested as well.

“I hadn't seen [the] original paper before that,” Tapanila says. Idaho #4, the very fossil that Almgreen used to make his own hypothesis, would be integral, Troll assured the duo, “if one wanted new insights and finally establish that the whorl was in the lower jaw.”

Publishing their findings in a landmark 2013 Biology Letters paper, Tapanila’s team used CT scans of Idaho #4 to reveal a view that Almgreen couldn’t see in the ’60s. Inside this fossil, they discovered all the parts of Helicoprion’s upper and lower jaw, which led to their reconstruction of the whorl that “partly confirms” Almgreen’s original hunch, Tapanila writes in the 2013 paper. “Idaho #4 became the Rosetta stone of sorts for deciphering these sharks,” Pruitt says. Indeed, the whorl was located on the lower jaw, just as Almgreen had suggested. But what Almgreen could not see, Tapanila says, is that it was attached to the full length of the shark’s jaw. These teeth “filled up its entire mouth.”

One of the paper’s more astounding findings shows that buzz sharks are not sharks at all. The scans revealed that they actually belong to the closely related ratfish family, ironic considering that one of Troll’s many sea life obsessions over the years happens to be with ratfish. He has one tattooed upon his upper bicep, and the fish inspired the name of his band, “The Ratfish Wranglers.” There's even a ratfish species, Hydrolagus trolli, that was named after him in 2002.

Troll’s comic-like depictions of the long-debunked Helicoprion hypotheses and his best take based on the new research are printed in the paper alongside Tapanila’s study. Since day one, “Troll was part of the science team,” Tapanila says. “He puts the pieces together.”

The most recent illustration shows Helicoprion with its mouth packed full of spiral-sawed teeth, reflecting the 2013 finding, which Tapanila says he’s pretty sure is spot on—“as sure as a scientist is ever willing to say that they’re sure.”

Though he’s played a true role in science, Troll remains unabashedly an artist. Scientists work within strict confines, he says. “They have to be cautious.” They know where Helicoprion fits in the family tree now, but they still need to learn what this ratfish looked like. “No one’s ever seen the body—all we have are the whorls,” Troll says, “and that’s where I come in.”

Troll’s “Buzz Sharks of Long Ago” will be on exhibit at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History for the summer of 2016 and at The Museum of The Earth in Ithaca, New York, the following year.

Editor's Note: The article has been updated to reflect the fact that "Dancing to the Fossil Record" was not Troll's first art exhibit.