Prehistoric Hyena’s Teeth Show Bone-Crushing Carnivore Roamed the Arctic

The only hyena to live in North America, Chasmaporthetes, had the stature of a wolf and the powerful jaws of its modern relatives

:focal(1019x676:1020x677)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/b6/deb6bafc-c7c9-4579-a2ea-29cea960d07e/1.jpg)

Over a million years ago, among the chilly grasslands of the ancient Yukon, Canada’s most northwesterly territory, an unexpected beast roamed: a hyena. More lupine in appearance than its modern relatives, but still adept at crushing bones with its powerful jaws, this "running hyena" was the only species of its family to venture out of Eurasia and spread to the Americas. Paleontologists know the prehistoric carnivore as Chasmaporthetes.

The first Chasmaporthetes fossils were named nearly a century ago from the vicinity of the Grand Canyon, and accordingly, the ancient hyena’s scientific name roughly translates to “the hyena who saw the canyon.” Since that initial discovery, additional fossils have turned up from California to Florida, from northern Mexico to Kansas, and additional species have been unearthed in Africa and Eurasia. But there was always a missing piece to the puzzle. Paleontologists found Chasmaporthetes fossils in Eurasia, and the ancient predator clearly ranged widely through southern North America, but the fossils bridging the gap in a place called Beringia, where Siberia and Alaska were once joined by a land bridge, were seemingly nowhere to be found. A newly analyzed pair of teeth is helping to fill in part of that story.

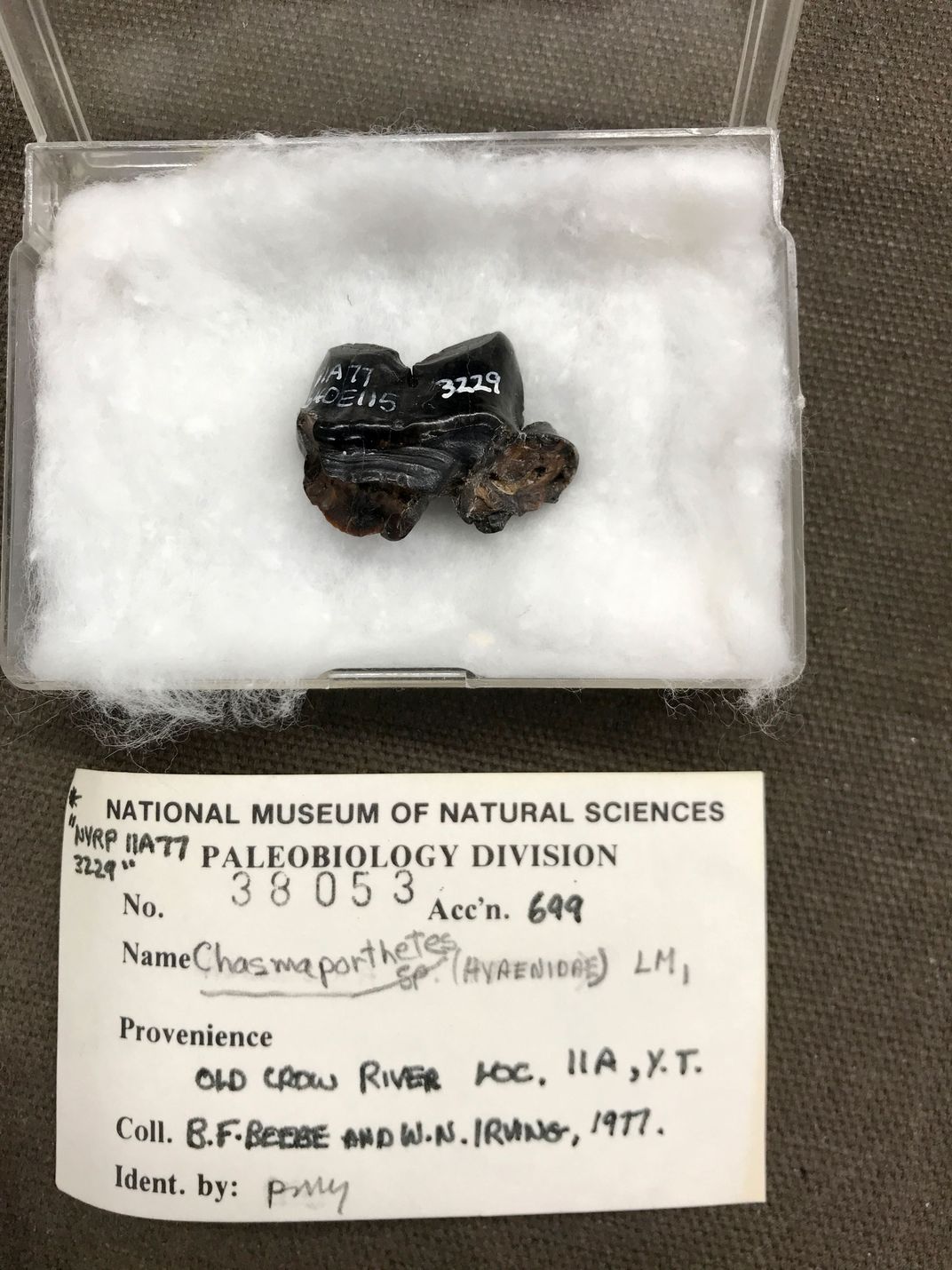

A team of paleontologists led by researchers from the University at Buffalo describe the fossils today in the journal Open Quaternary. The teeth were collected back in the 1970s, found in the Yukon’s Old Crow Basin—a place that has yielded over 50,000 vertebrate fossils representing more than 80 species. Even though the hyena teeth were known in certain paleontology circles, no formal study had ever been published. Whispers of Arctic hyenas piqued the curiosity of University at Buffalo paleontologist Jack Tseng, who over years of discussions with coauthors Lars Werdelin and Grant Zazula eventually tracked down the teeth and positively identified them. “This was classic paleo collection detective work, involving a network of collaborators and collections managers,” Tseng says.

What emerges is a view of the Ice Age that’s a bit different than typical visions of woolly mammoths and Smilodon, or Saber-toothed cats. Even though artistic depictions and museum displays sometimes depict many different Ice Age species together, Chasmaporthetes arrived in the Yukon during a very specific slice of time that would look a bit less familiar to us. “There were no bison, likely no lions, no gray wolves, no muskoxen, no saiga antelope,” says Zazula, a paleontologist at Simon Fraser University. All those animals arrived in North America later. Instead, the hyena was neighbors with giant camels, horses, caribou and steppe mammoths (a different species than the more familiar woolly sort). And despite the moniker “Ice Age,” the time of Chasmaporthetes was on the green side. “There were probably a few stunted spruce trees, with swaths of steppe-tundra grasslands with shrub birch and willows,” Zazula says. Nevertheless, the high latitude of the ancient Yukon still brought protracted chills and short summers, meaning the hyenas “had to have been effective predators in the long, dark, cold Arctic winters.”

From the fragmentary fossil record of the beast, paleontologists see North America’s only hyena as more wolf-like than its modern spotted cousin. “Based on what we know about the skull and limb skeleton of Chasmaporthetes in other fossil localities, we think this hyena was longer-legged, with a much less-sloped back, and probably did not live in groups as large as living spotted hyenas do,” Tseng says.

The two teeth aren’t the oldest Chasmaporthetes fossils in North America, Tseng says, as the oldest finds are about five million years old. But the million-year-old teeth are significant for two other reasons. They not only demonstrate that the hyena ranged over much of North America for millions of years, but they also were found right where paleontologists expected them to pop up. “The Arctic fossils cut that distance gap along the speculated dispersal route right down the middle, putting a dot on the map where hyena paleontologists predicted Chasmaporthetes should have traveled,” Tseng says.

How Chasmaporthetes fits into North America’s ancient ecology is still somewhat hazy. Like other hyenas, this ancient species had bone-crushing jaws that would have allowed it to bust carcasses into splinters. But that doesn’t mean chomping on bones was all the hyena did.

“I think because hyenas are bone crackers, people tend to associate them with scavenging,” Des Moines University paleontologist Julie Meachen says. “But the modern spotted hyena is a fierce predator that gives lions a challenge.” While it’s unlikely that Chasmaporthetes lived in large social groups, as suggested by their sparse distribution in the fossil record, Meachen says that the carnivore was more than capable of hunting live prey.

When Chasmaporthetes arrived in North America in the Pliocene, many of the other “classic” Pleistocene carnivores were not yet present. Gray wolves and lions wouldn’t arrive for tens of thousands of years. The hyena likely lived along cuons—relatives of today’s dholes—and scimitar-toothed cats, Zazula says, so the hyena might have lived during a window when there wasn’t too much competition for prey.

However, Chasmaporthetes did face some competition with another bone crusher. A prehistoric dog, Borophagus, overlapped with the hyena for about three million years in North America. The canid might have dominated southern habitats while Chasmaporthetes largely stayed north until Borophagus, whose name means “gluttonous eater,” went extinct. “They almost certainly were competing with bone-cracking dogs during their co-occurrence in the fossil record,” Meachen says.

The challenging Arctic landscape may have actually been an ideal place for a predator with such abilities. “In harsh environments with low abundance of prey, bone cracking was a necessary and advantageous trait to hyenas because they could gain more calories from being able to eat more of the prey,” Tseng says.

Like many Ice Age mammals, Paleontologists are still wrestling with the question of what exactly wiped out Chasmaporthetes. “Since Chasmaporthetes went extinct before the end-Pleistocene, obviously something other than that event did the deed for them,” Meachen says. The arrival of gray wolves in North America, and the profusion of native dire wolves, may have given the hyena some stiff competition, but what drove Chasmaporthetes to the brink is still an open question. “Overall, I think this is still a mystery,” Meachen says.

The loss of the continent’s bone-crushing hyena was no small matter. Even though wolves can and do crunch bones, none did so to the degree of Chasmaporthetes. The hyena played an important ecological role breaking down large carcasses out on the plains and spreading nutrients throughout their range. The loss of these carnivores, and the lack of a suitable successor, changed the nature of North America—the continent just isn’t the same without hyenas.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)