Puzzle of the Century

Is it the fresh air, the seafood, or genes? Why do so many hardy 100-year-olds live in yes, Nova Scotia?

Maybe its that her face is so smooth and pink or the way she aims her green eyes right into yours, talking fast and crisply articulating each word. Her gestures are as nimble as a hatmaker’s. You would be tempted to say Betty Cooper isn’t a day over 70. She’s 101. “If I couldn’t read, I’d go crazy,” she says, lifting the magazine on her lap. “I like historical novels—you know, Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn and all that kind of stuff. I get a big batch from the Books for Shut-ins every three weeks, and I read them all.”

Betty wears bifocals, and it’s no small thing to see as clearly as she does after watching a century go by. Though her hearing is not what it used to be, a hearing aid makes up for that. Complications from a knee operation more than 30 years ago keep her from walking easily. But she continues to live in her own apartment, in Halifax, Nova Scotia, with assistance from women who drop by to cook meals, run errands and help her get around.

Cooper’s health and independence confound the notion that living a very long life entails more pain and suffering than it’s worth. “I do have a problem remembering,” she allows. “I go to say someone’s name and it escapes me. Then five minutes later, I remember it.” Of course, lots of people half her age have that complaint.

Betty Cooper is a diamond-quality centenarian, whose body and and brain appear to be made of a special material that has scarcely worn down. But just being a Nova Scotian may have something to do with it. At least that’s the suspicion of medical researchers who plan to study Cooper and others in Nova Scotia to learn more about the reasons for their very long—and hardy—lives. In parts of Nova Scotia, centenarians are up to 3 times more common than they are in the United States as a whole, and up to 16 times more common than they are in the world population.

Why? Nova Scotians have their own theories. “We’re by the sea, and we get a lot of fresh air,” says Grace Mead, 98, of Halifax. “I’ve always been one for fresh air.” “

I was a very careful young girl,” says Hildred Shupe, 102, of Lunenburg. “I never went around with men.” “I mind my own business,” says Cora Romans, 100, of Halifax. “

The Lord just expanded my life, I guess,” says Elizabeth Slauenwhite, 99, of Lunenburg. “I’m in His hands, and He looked after me.”

Delima Rose d’Entremont, a tiny, brown-eyed woman of 103, of Yarmouth, says the piano helped keep her going. “I won two medals in music when I was younger, and I taught piano all my life,” she says, sitting straight in her wheelchair and mimicking herself at the keys. She occasionally performs for friends at her nursing home, Villa St. Joseph-du-Lac.

Cooper grew up on a farm in IndianHarborLake, on the province’s eastern shore, and remembers meals that few followers of today’s nonfat regimens would dare contemplate. “I ate the right stuff when I was growing up,” she explains. “Lots of buttermilk and curds. And cream—in moderation. And when I think of the homemade bread and butter, and the toast with cups of cocoa,” she says, trailing off in a high-calorie rhapsody. Then she adds: “I never smoked. And I never drank to excess. But I don’t know if that made the difference.”

In some ways, Nova Scotia is an unlikely longevity hot spot; a healthful lifestyle is hardly the provincial norm. Physicians say that despite abundances of brisk sea air, fresh fish and lobster and locally grown vegetables and fruits, Nova Scotians as a group do not take exceptionally good care of themselves. “The traditional diet is not that nutritious,” says Dr. Chris MacKnight, a geriatrician at Dalhousie University in Halifax who is studying the centenarians. “It’s a lot of fried food.” Studies show that obesity and smoking levels are high and exercise levels low. Also, the two historically most important industries—fishing and logging— are dangerous, and extract a toll. “In fact,” Mac- Knight says, “we have one of the lowest average life expectancies in all of Canada.”

Yet the province’s cluster of centenarians has begged for a scientific explanation ever since it came to light several years ago. Dr. Thomas Perls, who conducts research on centenarians at the BostonMedicalCenter, noticed that people in his study often spoke of very old relatives in Nova Scotia. (To be sure, the two regions have historically close ties; a century ago, young Nova Scotians sought their fortunes in what they called “the Boston States.”) At a gerontology meeting, Perls talked to one of MacKnight’s Dalhousie colleagues, who reported seeing a centenarian’s obituary in a Halifax newspaper nearly every week. “That was amazing,” Perls recalls. “Down here, I see obituaries for centenarians maybe once every five or six weeks.” Perls says he became convinced that “Nova Scotians had something up their sleeve” that enabled them to reach such advanced ages. “Someone had to look into it.”

MacKnight and researcher Margaret Miedzyblocki began by analyzing Canadian census data. They found that the province has about 21 centenarians per 100,000 people (the United States has about 18; the world, 3). More important, MacKnight and Miedzyblocki narrowed the quest to two areas along the southwestern coast where 100-year-olds were extraordinarily common, with up to 50 centenarians per 100,000 people. One concentration is in Yarmouth, a town of 8,000, and the other is in Lunenburg, a town of 2,600.

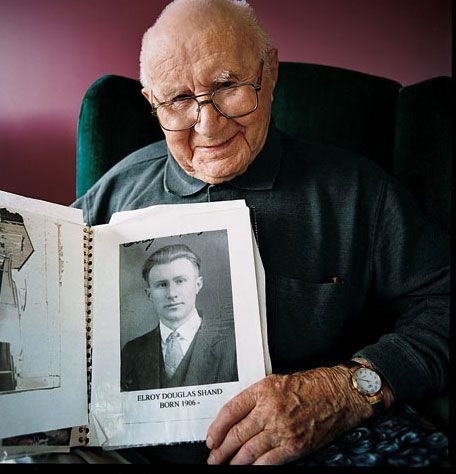

To the researchers, the notable feature was not that Yarmouth and Lunenburg were started by people from different countries. Rather, the key was what the two towns have in common: each is a world of its own, populated to a significant degree by descendants of original settlers. And as the researchers learned, longevity tends to run in families. Elroy Shand, a 96-year-old in Yarmouth, says he has a 94- year-old aunt and had two uncles who lived into their 90s. Delima Rose d’Entremont’s mother died at 95. Betty Cooper’s father died at 98. Says MacKnight: “It’s very possible that the 100-year-olds in Nova Scotia have some genetic factor that has protected them—even from all the bad effects of the local environment.”

Only a three-hour ferry ride from Bar Harbor, Maine, Nova Scotia extends like a long foot into the Atlantic, connected to New Brunswick by a thin ankle. Almost all the stormy weather that roars up the Eastern Seaboard crashes into Nova Scotia. In winter, powerful northeasters batter the province with snow and freezing rain. The windswept shoreline, the vast expanse of ocean beyond, and frequent low hovering clouds make the place feel remote.

Unlike most Nova Scotians, whose ancestors were English, Irish and Scottish, Lunenburg residents largely trace their heritage to Germany. In the mid-1700s, the province’s British government moved to counteract the threat posed by French settlers, the Acadians, who practiced Catholicism and resisted British rule. The provincial government enticed Protestants in southwestern Germany to immigrate to Nova Scotia by offering them tax-free land grants, surmising they would not sympathize with either the unruly Acadians or the American revolutionaries in the colonies to the south.

Settling predominantly along the south shore of Nova Scotia, the Germans eventually gave up on farming because the soil is so rocky. They turned to fishing and shipbuilding. For generations, they kept mostly to themselves, marrying within the community and hewing to tradition. Lunenburg has so retained its original shipbuilding, seafaring character that the United Nations has named it a World Heritage Site.

Grace Levy, of Lunenburg, is a petite 95-year-old woman with blue eyes, shining white hair and impossibly smooth skin. She has two sisters, both of whom are still living at ages 82 and 89, and five brothers, four of whom drowned in separate fishing accidents. She left school at age 13 to do housework for other families in Lunenburg. The hardships seem not to have dampened her spirit—or health. “My Dad said you’ve gotta work,” she recalls. “He was a kind of a hard taskmaster. He didn’t mind using a piece of rope on our back if we did the least little thing. But Mom was so good and kind.”

Grace married a man from nearby Tancook. Although the two were not blood relatives, their ancestries so overlapped they had the same last name. “My name has always been Levy,” she says with a smile that flashes white teeth. “I had a brother named Harvey Levy and I married a Harvey Levy.”

The town of Yarmouth was settled by New Englanders, but areas just to the south and north were settled by the French, whose plight is dramatized in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem Evangeline. It tells the story of lovers from Nova Scotia’s northern “forest primeval” who were separated during the brutal Acadian expulsion of 1755, when the English governor, fed up with the French peasants’ refusal to swear allegiance to Britain, banished them to the American colonies and Louisiana. Later, large numbers of Acadians returned to Nova Scotia and settled the coastline from Yarmouth north to Digby.

After their rough treatment by the English, the Acadians were not inclined to mix with the rest of the province. Today, many people in the Yarmouth area still speak French and display the blue, white and red Acadian flag. Local radio stations play Acadian dance music, a country-French sound not unlike Louisiana zydeco.

“The Yarmouth area would have been settled by only 20 or 30 families,” MacKnight says. “Many of the people who live there now are their descendants.” The question is, he says, did one of the original ancestors bring a gene or genes that predisposed them to extreme longevity, which have been passed down through the generations?

In Boston, Perls and his colleagues, who have been studying centenarianism for almost a decade, gathered promising evidence to support the notion of a genetic basis for extreme longevity: a woman with a centenarian sibling is at least eight times more likely to live 100 years than a woman without such a sibling; likewise, a man with a centenarian sibling is 17 times more likely to reach 100 than a man without one. “Without the appropriate genetic variations, I think it’s extremely difficult to get to 100,” Perls says. “Taking better care of yourself might add a decade, but what matters is what you’re packin’ in your chassis.”

Additional evidence comes from recent studies on DNA. Drs. Louis M. Kunkel and Annibale A. Puca of Children’s Hospital in Boston—molecular geneticists working with Perls— examined DNA from 137 sets of centenarian siblings. Human beings have 23 pairs of chromosomes (the spindly structures holding DNA strands), and the researchers discovered that many of the centenarians had similarities in their DNA along the same stretch of chromosome No. 4. To Perls and colleagues, that suggested that a gene or group of genes located there contributed to the centenarians’ longevity. The researchers are so determined to find one or more such genes that they formed a biotechnology company in 2001 to track them down: Centagenetix, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Scientists suspect there may be a handful of age-defying genes, and the competition to pinpoint and understand them is heated. Medical researchers and drug company scientists reason that if they can figure out exactly what those genes do, they may be able to develop drugs or other treatments to enhance or mimic their action. To skeptics, that might sound like the same old futile quest for a fountain of youth. But proponents of the research are buoyed by a little-appreciated fact of life for many of the super old: they’re healthier than you might think.

That, too, has been borne out in Nova Scotia. “I’m forgetful, I can’t help it,” says 96-year-old Doris Smith of Lunenburg. “But I’ve never had an ache nor a pain.”

“I can’t remember being sick, not a real sickness,” Hildred Shupe says. “But my legs are beginning to get kind of wobbly now. I don’t expect to live to be 200.”

Alice Strike, who served in the Royal Air Corps in World War I and lives in a veteran’s healthcare facility in Halifax, doesn’t recall ever being in a hospital before. She is 106.

Centenarians often are healthier and livelier than many people in their 70s or 80s, according to research by Perls. He says that 40 percent of centenarians avoid chronic illnesses until they’re 85 or older, and another 20 percent until they’re over 100. “We used to think that the older you were the sicker you were,” Perls says. “The fact is, the older you are, the healthier you’ve been.”

He speculates that longevity-enabling genes may work via several possible mechanisms, such as protecting against chronic diseases and slowing down the aging process. Then again, those processes may amount to much the same thing. “If you slow down the rate of aging, you naturally decrease susceptibility to illnesses like Alzheimer’s, stroke, heart disease and various cancers,” he says.

Clues to how such genes might operate come from a centenarian study being conducted by Dr. Nir Barzilai, a gerontologist and endocrinologist at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx. Barzilai has found that his research subjects—more than 200 Ashkenazi Jewish centenarians and their children—have abnormally high blood levels of highdensity lipoprotein, or HDL, a.k.a. the “good” cholesterol. The average woman has an HDL level of 55, he says, whereas the grown children of his centenarians have levels up to 140.

He believes that a gene or genes are responsible for the extremely high HDL levels, which may have helped the very old people in his studies maintain their sharp minds and clear memories. He says their high HDL levels, which are presumably controlled by genes, might protect them from heart disease; HDL clears fat from coronary arteries, among other things.

Other researchers say that longevity-enabling genes might protect people in much the same manner as caloric restriction, the only treatment or dietary strategy shown experimentally to extend life. Studies with laboratory rats have found that those fed an extremely low-calorie diet live at least 33 percent longer than rats that eat their fill. The restricted animals also seem to avoid ailments connected with aging, such as diabetes, hypertension, cataracts and cancer. Another possibility is that longevity-enabling genes limit the activities of free radicals—unpaired electrons known to corrode human tissue. Medical researchers have suggested that free radicals spur atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease, for instance. “Free radicals are a key mechanism in aging,” Perls says. “I wouldn’t be surprised if something to do with freeradical damage pops up in our genetic studies.”

If Macknight receives funding to pursue the research, he and his associates plan to interview Nova Scotian centenarians about their histories as well as examine them and draw blood samples for genetic analysis. He hopes to work with Perls to compare the Nova Scotians’ genetic material to that from Perls’ New England subjects, with an eye for similarities or differences that might betray the presence of longevity-enabling genes.

Like all students of the extremely old, MacKnight is interested in their habits and practices. “We’re trying to look at frailty,” MacKnight says, “or, what makes some 100-year-old people seem like they’re 60 and some seem like they’re 150. What are the differences between those who live in their own homes and cook their own breakfast and those who are blind and deaf and mostly demented and bed-bound? And can we develop some kind of intervention for people in their 50s and 60s to keep them from becoming frail?”

Not all centenarians—not even all of those in Nova Scotia— seem as young as Betty Cooper. And though it could be that the difference between the frail and the strong is determined largely by genes, researchers say it is also true that some people who reach 100 in fine shape have been especially prudent. Among centenarians, smoking and obesity are rare. Other qualities that are common to many centenarians include staying mentally engaged, having a measure of financial security (though not necessarily wealth) and remaining involved with loved ones. And though healthy nonagenarians and centenarians often say they’ve led physically active lives—“I did a lot of hard labor,” says 90-year-old Arthur Hebb, of Lunenburg County, who eagerly reads the newspaper every day—Perls and other researchers haven’t definitively answered that question.

Nor do researchers fully understand all the centenarian data, such as why the great majority are women. In the United States, women older than 100 outnumber men by more than four to one. But men at 100 are more likely than women the same age to be in good health and clearheaded. Perls and his colleague Margery Hutter Silver, a neuropsychologist, have found that about 70 percent of centenarian women show signs of dementia, compared with only 30 percent of the men. Asurprisingly high proportion of the women—14 percent—have never married. In contrast, almost all centenarian men are, or have been, married.

Whether they’ve survived so long because they’re resilient, or they’re resilient because they’ve survived so long, centenarians are often possessed of exceptional psychological strength. “They’re gregarious and full of good humor,” Perls says. “Their families and friends genuinely like to be with them, because they’re basically very happy, optimistic people.” Agenial attitude makes it easier for people to handle stress, he adds: “It isn’t that centenarians have never suffered any traumatic experiences. They’ve been through wars, they’ve seen most of their friends die, even some of their own children. But they get through.”

Paradoxically, that centenarians have lived such long and eventful lives makes it all the more difficult to pinpoint any one advantage they may have shared. No matter how much researchers learn about longevity-enabling genes, no matter how well they discern the biological protections that centenarians have in common, the very old will always be an exceptionally diverse group. Each one will have a story to tell— as unique as it is long.

“I started fishing when I was 14,” says Shand, of Yarmouth. “Then I built fishing boats for 35 years.” He uses a wheelchair because a stroke 18 years ago left him with some disability in his right leg. He is broad-chested, robust—and sharp. “I don’t think hard work ever hurt anybody.”

“We had a lot of meat and a lot of fish and fowl,” says Elizabeth Slauenwhite, 99, of Lunenburg. There were also “vegetables and fruit,” she adds. “And sweets galore.”