Rebuilding Greensburg Green

Everyone assumed this Kansas town was destined to fade away. What would it take to reverse its course?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Greenburg-SIPs-Home-Ext-631.jpg)

The sirens started blaring at 9:15 p.m., May 4, 2007. School supervisor Darin Headrick was returning from his son's track meet and decided to get to the safety of his friends' basement nearby, which was also a good excuse for a visit with them. "Usually you get a lot of wind and rain and hail," Headrick says. "And then a little tornado touches down in a couple places. It's not a big deal." But when they felt their ears pop with a sudden change of air pressure—ten times worse than what you feel in an airplane, according to Headrick, "we looked at each other and went: 'Oh no, this isn't good.'"

Amid the sound of shattering glass, they ran to a corner bedroom in the basement, shut the door in the darkness, and tried to cover the children on the floor. "From the time we shut the door until the house was gone was probably thirty seconds. There was nothing but storm and sky above." After the tornado passed, Headrick climbed up the rubble to peek out from the top of the basement. "When the lightning flashed we could see little rope tornados," he says, "just a couple skinny ones on the east side of town that were pretty close."

Then he and a few neighbors heard a woman next door yelling: "I'm in here! Help my baby! Please get my baby!" That house had had no basement. The woman had hidden in a closet with her baby as rafters splintered, bricks tossed, and the family car flew overhead, spattering the baby with its transmission fluid. The walls had collapsed over them.

Hedrick and the others rushed over and shined their flashlight on a little foot; they pulled away more boards and bricks until they could lift out the infant.

"And the baby wasn't crying," Headrick recalls, "just big eyes looking up like: 'man, where you been?'" They were relieved to figure out that the red all over the child wasn't blood, just transmission fluid; the mother was bruised but able to walk away with them.

"We just thought it was these five or six houses on the south end of town that got hit, because it was dark and raining and we couldn't see anything." It wasn't until they and other people started walking into town that they realized ... there was no town.

Typical tornados cover about 75 yards of ground at a time. The monster that chugged north along Main Street was 1.7 miles wide at its base, smashing or blowing away everything between the east and west edges of the 2-mile-wide town.

Twelve people died from the town of 1,400. About 95 percent of the homes were destroyed. Headrick's school, the hospital and the John Deere dealership were gone.

The next night, a smaller storm passed through the region. People still in town met in the basement of the courthouse, the only structure that still offered some protection. Gathering together with the mayor and city officials to talk about Greensburg's survival was not exactly a novel experience for these folks. Like most small Midwestern towns, Greensburg had been losing jobs, entertainment, and population—especially young people, with the school population cut in half in recent decades. According to Headrick, "we were probably destined to the same outcome every other small rural town is, and that is, you're going to dry up and blow away." Why bother rebuilding? "We thought: What can we do that gives our community the best chance to survive in the long term? What would make people want to move to our community?"

No one is sure who first voiced the green idea, because it occurred to many people simultaneously. They could leave to start over elsewhere, they could rebuild as before only to watch their town slowly die—or, as Bob Dixson, who has since become mayor, says, "we could rebuild in a green, energy-efficient manner that would leave a legacy to future generations." As the conversation gained momentum, the people became excited with their unique opportunity to start from scratch, to live up to their town's name—and perhaps to run an experiment that could lead others into greenness by proving its value.

When President Bush visited a few days later, he stood on the debris of the John Deere dealership and asked the co-owner: "What are you going to do?" Mike Estes answered that they were going to rebuild.

Governor Kathleen Sebelius heard that Greensburg was planning to rebuild green. At a Topeka Statehouse news conference, she announced, "we have an opportunity of having the greenest town in rural America." The leaders of Greensburg decided to do one better: They wanted the greenest town in America, rural or urban.

A reporter trying to make sense of this sudden enthusiasm for greenness soon learns that nearly everyone in Greensburg makes the same two points. First, greenness didn't start with city slickers. As Mayor Dixson puts it: "In rural America, we were always taught that if you take care of the land, the land will care of you. Our ancestors knew about solar, about wind, and geothermal with their root cellars to store their crops through the winter. They used windmills to pump water for their cattle. They used water to cool their eggs and their milk. And then they pumped it up above, and the sun heated it and they had a hot shower at night. We've been aware of the concepts in rural America. We knew that you had to be good stewards of the land and the resources. It's just that now we have such advanced technology to take advantage of."

Daniel Wallach, a relative newcomer to the community, had long been passionate about green technologies. When he brought a concept paper to a town meeting a week after the tornado, he found that the people needed no convincing. "These are people who live off the land," says Wallach. "Ranchers and farmers are the original recyclers—they don't waste anything. They innovate and are very ingenious in their responses to problem solving, and all of that is very green."

But couldn't Greensburg have done all this before the tornado? Sure, the seeds of greenness were there all along, but what caused them to sprout now, in particular? That evokes the second motive people keep bringing up: their belief in a higher purpose. They say their search for meaning in the face of disaster has led to their resolution to be better stewards of this world.

"I think it's more than coincidental that this town's name is green," maintains Mike Estes. "I think there's some providential irony here that God had in mind, because that is bringing our town back."

Such sentiments go a long way toward explaining why most Greensburgians show so much resolve. FEMA made it clear from the outset that it could offer advice and financing to replace what was lost, but it could pay nothing toward the extra costs involved in rebuilding green. Tax incentives were minor compared to initial outlays. In large tent meetings attended by 400 of the townspeople at once, the leaders committed to going green regardless.

An architecture and design firm in Kansas City called BNIM showed town leaders what would be required to rebuild according to the U.S. Green Building Council's specifications. And Daniel Wallach helped map out the broader vision: "if we can be that place where people come to see the latest and greatest, we think that that's going to provide the economic base we need, both in terms of tourism and ultimately green businesses locating in Greensburg. I see the town itself being like an expo or science museum, where people come to see the latest and see how it all works."

Twenty-one months later, 900 people have returned so far. Most of them have moved out of the temporary trailers, called FEMA-ville, and most have become experts at rebuilding green. Mike Estes gazes out beyond his rebuilt John Deere building to view the rest of town—which still looks like a disaster zone from most angles, a landscape of tree stumps. Yet, he says, "It's pretty incredible progress that's been made. A lot of that can be credited to going green. It's giving us the momentum that we didn't have before."

And last week, Mayor Dixson sat in the gallery as a guest of first lady Michelle Obama during President Obama's first address to Congress. The President pointed to Greensburg residents "as a global example of how clean energy can power an entire community."

The town is becoming a showcase for a series of firsts in applying energy-efficient standards. It recently became the first city in the United States to light all its streets with LED streetlights. The new lamps focus their beams downward, reducing the amount of light usually lost to the sky and allowing people to see the stars once again. They are also projected to save 70 percent in energy and maintenance costs over the old sodium vapor lights, lessening Greensburg's carbon footprint by about 40 tons of carbon dioxide per year.

Greensburg's 5.4.7 Arts Center, named for the date of the town's destruction, is the first building in Kansas to earn a LEED Platinum certification—which is no small feat. Developed by the U.S. Green Building Council, LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification is based on six categories: sustainable sites, water efficiency, energy and atmosphere, materials and resources, indoor environmental quality, and innovation and design. The rating system qualifies buildings according to levels of simple certification, Silver, Gold, and at the top, Platinum.

Designed and built by graduate students of the University of Kansas School of Architecture, the 5.4.7 Arts Center is powered by three wind turbines, eight solar panels, and three geothermal, 200-foot-deep wells. At that depth the temperature is around 55 degrees Fahrenheit, which cools water that is then pumped up to chill the air in summer. In winter, relatively warm below-ground temperatures warm the water. Either way, less energy is required than in conventional heating and cooling. The tempered-glass-covered building also demonstrates passive solar design; it is oriented to take full advantage of heat from the southern sun in winter.

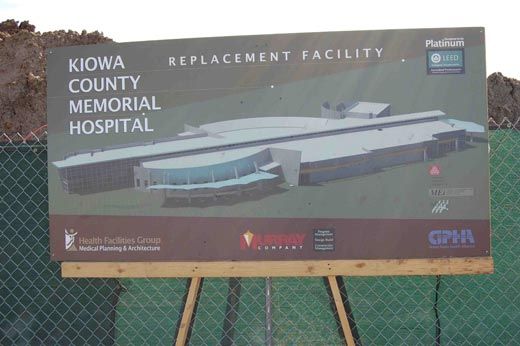

And that was just the beginning. Greensburg's new city hall, hospital, and school are all now being built with the goal of achieving LEED Platinum standards. A wind farm is being planned on the south side of town.

Daniel Wallach founded a nonprofit called Greensburg Greentown to attract outside companies to try out their most promising technologies in Greensburg. "Given the small scale of our town, it really lends itself to being a platform for even small companies that have good ideas—a lot like a trade show—that's what we want to be for these companies."

Among other projects, Greensburg Greentown is organizing the building of up to 12 "eco homes," each modeling a different design. Wallach calls them "a science museum in twelve parts: the only science museum that you can spend the night in." People thinking about building green, he says, can come and experience a variety of energy efficient features, green building styles, sizes and price ranges. "So before they invest in their new home, they get a real clear sense of the kinds of wall systems and technologies that they want to integrate into their house—and see them in action." One of the twelve homes has been built, an award-winning solar design donated by the University of Colorado. The second, shaped like a silo, is halfway through construction.

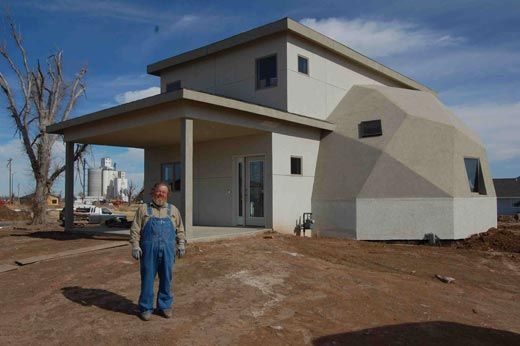

A number of proud homeowners have undertaken green designs on their own. Scott Eller invites John Wickland, a volunteer project manager for Greensburg Greentown, to tour the interior of his eye-catching domed home.

"This whole house is built out of 'structurally insulated panels' (SIPs), which are solid styrofoam laminated to oriented strand board on both sides," explains Eller. A builder in Lawrence, Kansas, found them to be the most efficient way to fit these 8 x 40 panels into dome shapes. They are well insulated and fit together tightly, preventing heat loss. Even better, given concerns about high winds and tornados, "these have survived what they call the 205-mph two-by-four test, which they shoot out of a cannon, and when it hits these, it just bounces off," Eller says.

Much of going green is also about the little things, and Wickland encourages Eller to take some dual-flush toilets off his hands. Wickland’s own living room is congested with large boxes of water-saving plumbing manifolds. An Australian company donated 400 toilets, stored in a warehouse nearby, that together could save 2.6 million gallons of water a year.

Bob and Anne Dixson invite Wickland over to see their new home, which is partly surrounded by a fence made out of recycled milk jugs and wheat straw. "It looks like wood," says the mayor, "but you never have to paint it, and it doesn't rot." Inside, they have built and wired the house with a "planned retro-fit" in mind. "When we can afford it," says Anne, "we'll be able to put solar on the south part of the house and retrofit that. Technology is changing so fast right now, and the prices are coming down all the time."

Mennonite Housing, a volunteer organization, has built ten new green houses in Greensburg and plans to build as many as 40 more. Most people are choosing to scale down the size of their homes, but otherwise, as Community Development Director Mike Gurnee points out, "you can have a green house and it can look like a traditional Cape Cod or a ranch house. It can be very sustainable without looking like it came from Star Wars."

The National Renewable Energy Lab (NREL), part of the Department of Energy, is advising people on how to design green and energy-saving features in their new homes. NREL has tested 100 recently built homes in town and found that, on average, they consumed 40 percent less energy than required by code. Community Development Director Mike Gurnee notes that, "with some of the houses, now that they're getting their utility bills, they see that the increased cost of construction is being made up rapidly with the smaller cost for utilities. They remember that in their prior house, their heating bill was $300, and now it's under $100."

Some energy-saving features, like geothermal heating systems, are just too expensive for most homeowners. "If we could really have started from scratch," says Gurnee, "if we could have erased property lines, I'd have liked to have tried geothermal or wind turbine or solar system on a block and have the cost shared by all the houses." That's not something that's been done on a large scale anywhere else in the United States. But, according to Gurnee, when the town expands and a developer subdivides new lots, "I want to make sure that there's a provision in our subdivision regulations so that the lots can be situated so that alternative energy sources can be shared among people on the block."

The first retail food store to rebuild was a Quik Shop/Dillons, which was designed as a national prototype to implement energy-saving features including extensive skylighting, efficient coolers and motion sensors that light up refrigerated cases only when people are near.

This month the LEED Platinum-targeted Business Incubator Building will open on Main Street, with funding provided by SunChips, the U.S.D.A., and actor Leonardo DiCaprio. The building will offer temporary, low-rent office space for ten small and emerging businesses being encouraged to return to the community.

The new John Deere dealership not only has a couple of its own wind turbines, but has begun a new business, BTI Wind Energy, to sell them internationally. The building combines skylights with mirrored reflectors to direct light as needed. Fluorescents are staged to come on partially or fully according to need on darker days, and the entire showroom makes use of motion detectors to use lights only when people are present. "You can imagine in a building this size what kind of energy we can save by doing that," says Mike Estes.

After the tornado, school superintendent Headrick had just a few months to get temporary facilities in place for the next school year. He also had to come up with long-range plans to make it worthwhile for families to return. He succeeded on both counts. Today, while providing for a growing student body in trailers, he is also supervising the design of a new school that he hopes will achieve LEED Platinum certification.

The new school will feature natural daylighting, meaning that most rooms will receive enough illumination from windows and skylights that artificial lights will seldom need to be turned on. All the heating and cooling will be done with geo-thermal heat pumps. "There are 97 geo-thermal wells we have to drill," says Headrick.

He hopes to generate all the school's electricity from wind power. As for water reclamation: "we'll have water cisterns both below ground and above ground. Any water that falls on our building will be captured and transported through roof lines. And we'll use that rain water that runs off to do any irrigation that takes place on the facility."

Do Greensburg's young people care about clean energy and recycling? Charlotte Coggins, a high school junior, says, "a lot of people think it's way nerdy, it looks dumb. They've been raised that way."

"My family wasn't against it," says another junior, Levi Smith. "My dad always thought wind generators and recycling made sense. But we never really did it—until after the tornado." A few in the community still ridicule alternative energy, seeing it as a radical political issue. "Those negative feelings are dying fast," says Smith.

Taylor Schmidt, a senior in the school's Green Club, agrees: "It's really encouraging that every day more kids are learning about it and figuring out: 'Oh, this really makes sense.' Every day the next generation is becoming more excited about green, and everything it entails, whether it be alternative energy, conservation, recycling—they get it, and they choose to be educated. This affects every single person on earth, every single life, now and to come."

Greensburg gets it. Old and young, they have been on a faster track in their green education than perhaps any other people on earth. "In the midst of all the devastation," says Bob Dixson with a slight quaver in his voice, "we have been blessed with a tremendous opportunity, an opportunity to rebuild sustainable, to rebuild green. It brought us together as a community, where we fellowship together and we plan together about the future. So we've been very blessed, and we know we have a responsibility to leave this world better than we found it."

And that's how a tornado became a twist of destiny for Greensburg, ensuring that a town expected to "dry up and blow away" met only half its fate.

Fred Heeren is a science journalist who has been writing a book about paleontology for so many years that he says he can include personal recollections from the Stone Age.