The Return of the Great American Jaguar

The story of tracking a legendary feline named El Jefe through the Arizona mountains

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4f/0b/4f0b33a9-cf00-4c3c-ba18-231f0cd3b2c9/oct2016_e06_jaguar.jpg)

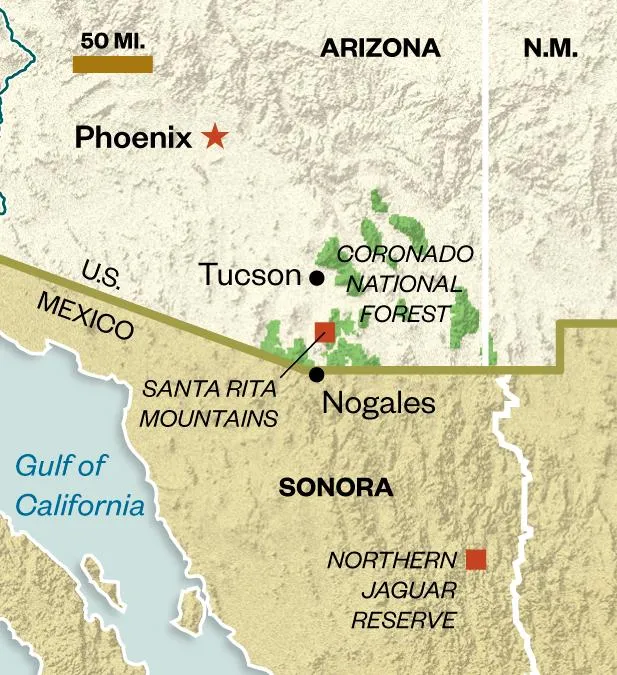

The jaguar known as El Jefe—The Boss—was almost certainly born in the Sierra Madre of northwest Mexico. Chris Bugbee, a wildlife biologist who knows El Jefe better than anyone, guesses that his birthplace was in the 70-square-mile Northern Jaguar Reserve in the state of Sonora. A team of American and Mexican conservationists do their best to protect the dwindling jaguar population there, and it’s within range of the Arizona border, where El Jefe made his fateful crossing into U.S. territory.

The gorgeous leopard-like rosettes were there in his fur at birth. Each jaguar has its own arrangement of these patterns, making individuals easy to identify. El Jefe has a heart-shaped rosette on his right hip and a question mark over the left side of his rib cage. Like all newborn jaguar cubs, he came into the world blind, deaf and helpless, and gradually acquired his sight and hearing over the first few weeks. By three months, the cubs have been weaned from milk to meat, but for the most part stay in the den. “It’s a lot of waiting around for mom to get back from a hunting trip,” says Bugbee.

By six months, the cubs are emerging under maternal supervision. Aletris Neils, a fellow biologist and Bugbee’s wife, studied a jaguar mother at the reserve in Sonora. “She would always stash her cubs on a high ridge while she hunted down in the canyons,” says Neils. “When she made a kill, she would carry the meat uphill to her cubs, rather than invite them down into possible danger.” Neils thinks El Jefe’s mother may have done the same thing, and that might partially explain his liking for high slopes and ridges as an adult, although all cats seem to enjoy a vantage point with a view.

At a year and a half, the young jaguars start making walkabouts by themselves. They leave and come back again, making trial runs. Neils compares them to human teenagers who come home with dirty laundry expecting a meal. For young male jaguars, it soon becomes impossible to return home. Bigger, stronger, older males will challenge them if they try. The young males have to disperse into new territory, and every few years, one of them will walk north from Mexico into Arizona.

We associate these sleek, swaggering, immensely powerful cats with Latin American jungles, where their populations are highest, but jaguars used to live all across the American Southwest, with reports of sightings from Southern California to the Texas-Louisiana border. They were hunted out for sport and their beautiful pelts and because they posed a threat to cattle. They were trapped and poisoned by semi-professional hunters who were paid a bounty by the federal government. The last recorded female jaguar in the United States was shot dead in Arizona in 1963.

El Jefe is the fourth documented male jaguar to make the border crossing in the last 20 years. Scenting the air for prey and threats and water, prowling through the night with the rocky ground under his cushioned footpads, conscious of the need for stealth and a safe place to sleep in the daytime, hyperaware of sounds and movement, this young cat could never have known, or cared, that he was walking into a political firestorm.

El Jefe, as he was named by excited local schoolchildren, found his way to good jaguar habitat in the Santa Rita Mountains near Tucson, and there he took up residence. In theory, jaguars and jaguar habitat enjoy legal protection in the United States under the Endangered Species Act. That theory is now being put to the test, because a Canadian mining company, Hudbay Minerals Inc., intends to build a gigantic open-pit copper mine in El Jefe’s home territory. If the project goes ahead, the Rosemont Mine will be the third-largest copper mine in the U.S., with a dollar value estimated in the tens of billions.

For the environmentalists battling the mine, El Jefe has become a vital tool in the courts, and a rallying symbol in the battle to sway public opinion. In Tucson, a craft beer has been named after him, and a mural attests to his popularity. On the other side of the political spectrum, El Jefe has been demonized as a Mexican intruder and a menace to rural families, even though jaguar attacks on humans are incredibly rare.

Supporters of the mine are outraged that one lone Mexican jaguar could hold up such a beneficial project, promising at least 400 jobs and a $701 million annual boost to the local economy over 20 years. Those figures are considered outrageously inflated by opponents of the mine. They predict that most mining jobs would go to existing Hudbay employees, with the bulk of the copper being sold to China, and the profits banked in Canada.

Meanwhile, El Jefe sleeps away the days under shade trees, rock outcroppings and in caves. He comes out to hunt in the star-studded Arizona nights, stalking his prey with precise micromovements, and then charging with overwhelming force and crushing their skulls in his jaws. White-tailed deer are abundant, and smaller, slower animals make easy meals. Following discreetly in the jaguar’s footsteps, Chris Bugbee often comes across the remains of luckless skunks. El Jefe eats everything except the rear end, which contains the noisome scent glands, and the fluffy tail.

**********

The dog known as Mayke is a 65-pound Belgian Malinois with long pointed ears and an affectionate disposition. She was born in Germany, where the breed is often used in aggressive police work, and shipped off to the U.S. Border Patrol.

Her new handlers trained her to detect drugs and explosives. She flunked out. Mayke is a highly intelligent dog with an excellent nose, but she scares easily and hates loud noises. Faced with a big, rumbling 18-wheel truck with hissing air brakes at a highway checkpoint, her tail would tuck and she would tremble. The Border Patrol gave up on her in early 2012.

At that time, Bugbee had settled in Tucson, after completing his master’s degree on alligators at the University of Florida. Neils, who had studied black bears in Florida, was doing her PhD at the University of Arizona, hence the move to Tucson. While Neils was at school, Bugbee was training dogs not to attack rattlesnakes. He heard about Mayke from a Border Patrol dog trainer, and dreamed up an entirely new profession for her. He would turn her into the world’s first jaguar scent detection dog, and use her to track the movements of a young male jaguar who had shown up in Arizona.

A Border Patrol helicopter pilot had reported seeing a jaguar in the Santa Rita Mountains in June 2011, but the first documented sighting of El Jefe was in the nearby Whetstone Mountains in November 2011. A mountain lion hunter named Donnie Fenn and his 10-year-old daughter were riding with their hounds, 25 miles north of the Mexican border. The hounds treed a big cat, and when Fenn arrived on the scene, he was thrilled to see that it was a jaguar.

El Jefe was 2 years old and weighed about 120 pounds, but he looked so menacing and powerful that Fenn guessed his weight at 200 pounds. He stood there taking photographs, awestruck by the jaguar’s “sheer aggressiveness” and “unreal” roaring. He was used to mountain lions (also known as pumas or cougars), which vocalize aggression by snarling, but jaguars roar and growl like African lions. After the jaguar descended from the tree, the hounds gave chase, sustaining minor injuries as El Jefe swatted at them before Fenn called his dogs off. When the hounds backed away, the cat was able to make his retreat.

To train Mayke for her new profession, Bugbee procured some jaguar scat from a zoo, and put it inside a short length of PVC pipe drilled with holes. He added a smear of scat from an ocelot, another rare and endangered spotted cat that turns up in southern Arizona. “That pipe was Mayke’s toy, and for two weeks we played fetch with it, so she’d learn the smells,” says Bugbee, a tall, strong, dark-haired man in his mid-30s, with striking green eyes.

Then he started hiding the toy, so Mayke would use her nose to find it. He trained her to bark when she found it. The next stage was to remove the jaguar scat, and hide it in the desert scrub behind the Bugbee-Neils house on the edge of Tucson. When Mayke found the scat and barked, Chris gave her the toy as a reward. “Mayke won’t bark for anything but jaguar or ocelot scat,” he says. “We do drills twice a week to keep it fresh in her mind.”

**********

While Bugbee was training Mayke, he started working as a field technician for the University of Arizona’s Jaguar Survey and Monitoring Project. It was overseen by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and funded with $771,000 of “mitigation money” from the Department of Homeland Security. The idea was to do something for wildlife, and wildlife advocates, after a new security wall was built along sections of the Mexican border. The wall has shut down many wildlife migration routes, but jaguars, ocelots and other species are still able to cross the border through rugged areas where no wall has been built.

Bugbee began by placing and monitoring motion-activated trail cameras in the backcountry of the Santa Rita Mountains. Then he got clearance to use Mayke, though the chances of finding jaguar scat in the mountain range seemed incredibly remote, even to Bugbee himself. “In arid country like this, scat only holds its scent for three days,” he says. It took several months and many hard steep miles, but finally, Mayke found some fresh scat under a manzanita bush and barked.

Bugbee didn’t praise her, or reward her with the toy, in case she was mistaken. He collected the scat and took it to the lab for genetic testing. Sure enough, it was jaguar. From its discreet placement under a bush far from any game trails, he learned that El Jefe was still cautious and unsure of himself in this new territory—“he definitely wasn’t advertising his presence.”

**********

In a four-wheel-drive truck borrowed from his father-in-law, with camping supplies in the bed and Mayke curled up on the back seat, Bugbee turns south from Interstate 10 toward the small town of Sonoita, Arizona. For the first time, he’s agreed to take a journalist into some of El Jefe’s favorite haunts.

The landscape is reminiscent of Kenya. Mountain ranges climb up into the sky from lion-colored plains and rolling grasslands. Thorny trees line the dry watercourses. The biggest mountains in sight are the Santa Ritas, rising to 9,400 feet and mantled with pine forest at higher elevations. Outside southern Arizona, says Bugbee, these unique “Sky Island” mountain ranges are relatively little known. Ranges like the Santa Ritas, marooned from each other in a sea of desert and grasslands, used to be the main strongholds of the Chiricahua Apaches, under legendary chiefs like Cochise and Geronimo.

“When the Apaches were here, there were grizzly bears, wolves, mountain lions, jaguars and ocelots in the Sky Islands,” says Bugbee. “The grizzlies and wolves are gone. The mountain lions are still here, and the jaguars and ocelots keep showing up. I think Arizona should prepare to receive these animals, because the species are migrating north, but that’s not congruent with open-pit mining and a border wall.”

He turns into the Santa Rita foothills on a rough, rocky dirt road, passing cactuses and mesquite trees, and ocotillo plants with long thorny wands tipped with scarlet flowers. Cattle huddle in patches of shade, having grazed the land around them into dust. Despite the overgrazing by privately owned cattle in this national forest, Bugbee says, the native wildlife is doing remarkably well.

“El Jefe found plenty to eat here,” he says. “He was 120 pounds when he arrived. Now he’s a big adult male in his prime. He’s grown into his name.”

Bugbee has spent four years trailing, studying and dreaming about El Jefe. Thanks to Mayke, he has come across very fresh scat, but he seldom finds a track, because El Jefe prefers to walk on rocks whenever possible. His skunk-eating is unusual for a jaguar, and he’s highly inquisitive. “When I put up a camera and come back to check it a few days later, he’s often the first photograph on the card,” says Bugbee. “Sometimes he’s there at the camera just a few minutes after we leave.” The jaguar has undoubtedly watched the man and dog in his territory, but in four years of mounting obsession, Bugbee has never set eyes on El Jefe.

“Obviously I would love to see him, but I’ve never pushed hard to get close,” he says. “I don’t want to disturb him, or affect his behavior. And I like my dog. I don’t want to see him grab Mayke in his jaws and end her life right in front of me.” On one occasion, he’s almost certain that Mayke saw El Jefe. “She froze in her tracks, then stood behind me with her tail tucked. She was terrified. It had to be him.”

The road gets steeper and rougher. Crawling and jouncing in four-wheel-drive, we pass through a patchy forest of junipers, oaks and pinyon pines, with slashing canyons falling away on either side, and the pine-clad peaks high above us. Bugbee parks on a small bench of level ground, pulls on a daypack with water and food, and clips a radio collar on the excited Mayke. We’re going to check some cameras in remote canyons, and look for scat and other signs of El Jefe’s presence.

“We’ll go fast and quiet,” says Bugbee. “Mayke will keep the bears away. The mountain lions shouldn’t bother us. The only humans I’ve ever seen out here are Mexican drug-packers. If we run into them, we’ll be calm, confident, not too hostile, not too friendly.”

He sets off boulder-hopping down a canyon. Mayke scrambles and disturbs four deer that bound away with white tails lifted. A troop of coatimundis studies us, then scatters. These bowlegged, long-snouted, raccoon-like animals are yet another species whose northern range extends into southern Arizona.

After an hour of hiking in 100-degree heat, we reach the first motion-activated camera. In the last ten days it has taken 70 photographs. Thumbing through the files, Bugbee notes squirrels, a bobcat, a gray fox and two men with big heavily laden backpacks. Mayke lies down in the shade and pants like a speeding train.

Another half-hour, and a rattlesnake encounter, brings us to the second camera. It has recorded images of a black bear, a bobcat, three different mountain lions and two more drug-packers. But no spotted cats. It’s been more than five months since the last photograph of El Jefe, and although such gaps in the record are not uncommon, Bugbee is starting to get concerned. “There’s no way of knowing where he is, or if he’s alive,” he says. “I’d love to get a radio collar on him, but you can’t even mention that idea in Arizona. It’s radioactive.”

**********

In 2009, an elderly jaguar known as Macho B—estimated to be 16, equivalent roughly in age to a 90-year-old man—was illegally baited, snared, tranquilized and radio-collared by biologist Emil McCain, a contractor working for the Arizona Game and Fish Department (AZGFD). Macho B injured himself trying to break out of the snare. The tranquilizer dose was wrong. Twelve days later, the dying, disoriented jaguar was captured and euthanized. He had been the only known jaguar in the U.S.

AZGFD then claimed that Macho B had been snared accidentally in a mountain lion and bear study. When that was exposed as a lie, USFWS investigators went after the whistle-blower, a research assistant named Janay Brun, who, under orders from McCain, had illegally baited the snare. McCain claimed he had been encouraged to catch and radio-collar the jaguar by his superiors—a charge denied by USFWS. Brun and McCain were prosecuted. As a result of this ugly, tragic saga, the idea of radio-collaring another jaguar in Arizona is anathema both to environmentalists and wildlife officials.

That night, with clouds scudding across the moon, Bugbee lights a cigar and tells his own story of intrigue and betrayal. Something about jaguars, he says, seems to bring out the worst in agencies and institutions that should be protecting them.

During his three years with the Jaguar Survey and Monitoring Project, Bugbee was able to get dozens of photographs and video clips of El Jefe. Mayke sniffed out 13 verified scat samples. When the project funding ran out in the summer of 2015, Bugbee wanted to continue his research. He approached the U.S. Forest Service, AZGFD and USFWS for funding, but all three agencies turned him down. Next he went to the Center for Biological Diversity, an environmental organization based in Tucson.

The Center, as it’s known, is spearheaded by a team of attorneys who file lawsuits under the Endangered Species Act. The organization also has a long adversarial relationship with the regional office of the USFWS. Randy Serraglio, the Center’s jaguar expert, contends that the agency demonstrates “a recurring pattern of caving in to political interests.”

It took several lawsuits filed by the Center, from 1994 to 2010, for the agency to grudgingly list jaguars as an endangered species in the U.S., and designate “critical habitat” for them in the Santa Ritas and other nearby mountain ranges. USFWS argued that the occasional lone wandering male jaguar did not constitute a viable population worth protecting, and that the species was not endangered on the other side of the border.

Kierán Suckling, the founder and executive director of the Center, agreed to fund Bugbee’s continuing research through donor-funded Conservation CATalyst, an organization Bugbee and Neils founded to promote awareness of big cats and advocate for protection. Neils started and Serraglio led a publicity campaign that championed El Jefe as the main reason to stop the mine.

Neils began making presentations in local schools about El Jefe and jaguars in the Southwest, and Bugbee headed back into the Santa Ritas with Mayke and a new set of cameras. Although funded by the Center, he was still operating under the university’s research permit and driving a loaner field vehicle from the university. By now, he knew many of El Jefe’s preferred watering holes, hunting areas and routes of travel, and he was able to record stunning video footage of the big, stocky jaguar crossing a rocky stream and swaggering toward the camera. El Jefe has a big, wide mouth and he keeps his muzzle open, drinking in the scented air and brushing it across his palate and nasal passages.

“I got amazing video on the U of A cameras, too, but it was all locked away in the vaults, none of it made public,” says Bugbee. “Nobody wanted to do any advocacy for jaguars, or say a word against this mine going into the best jaguar habitat we’ve got—not the university, not the wildlife agencies. El Jefe was like a dirty little secret they wanted to keep quiet. It didn’t sit right with me. It kept me up at night.”

For months, Bugbee and Neils kept their own video footage under wraps. They knew it was a powerful publicity weapon against the mine, but they worried that some hunter or mine supporter might see the footage and go into the mountains to kill El Jefe. In February 2016, they decided to risk going public.

In conjunction with the Center, Conservation CATalyst released an edited 41-second video clip of El Jefe, with the information that he was the only jaguar in the United States, and that his life was threatened by a huge open-pit copper mine. “That’s when all hell broke loose,” says Bugbee.

The video went viral; it reached an audience of 23 million people on one science Facebook page alone (“I F---ing Love Science”). It was broadcast in 800 television news stories, with a viewership of 21 million in the U.S. Worldwide, the Center estimates that 100 million people saw the video. There was a massive outpouring of support for El Jefe.

“My phone rang for two days straight,” says Bugbee. “‘Good Morning America’ called, the BBC. I heard from friends in Vietnam, Australia, Sumatra who had seen the video. It was very positive for jaguars, and it produced a very negative reaction from U.S. Fish and Wildlife and the University of Arizona.”

A regional supervisor at USFWS called Neils and told her to stop the jaguar outreach program in the schools and return educational materials borrowed from the agency. Bugbee says he was threatened with legal action for harassing an endangered species. The University of Arizona removed his name from the research permit and took away his field vehicle. When the final report for the Jaguar Survey and Monitoring Project was made public, after a long delay and a Freedom of Information Act request from a Tucson journalist, Bugbee saw that his name had been removed as one of its authors, even though he had written most of the draft.

Melanie Culver, who led the project at the University of Arizona, had met with Bugbee in September 2015. “We told him he could not release project photos, or videos, through the Center,” she says. “It has to go through U.S. Fish and Wildlife. He went ahead and released the video through the Center.”

The implication of her statement seems clear enough. The university is under contract with USFWS to produce unbiased scientific research on jaguars and ocelots. Bugbee, acting against her specific instructions, tainted the university’s neutrality by linking the research to an advocacy group.

Steve Spangle, USFWS field supervisor for the Southwest Region’s Arizona Ecological Services office, says Bugbee violated the terms of the research permit. “It was a stipulation that any images released must be approved by us, and cropped if necessary so that landmarks can’t be recognized,” he says. “That video is not cropped. That was our biggest concern, that it was endangering the animal.”

**********

The coffee pot is simmering on the campfire as the sun comes up. The air is hot, parched and still. Mayke gets up stiff and hobbling, but soon limbers up when we start hiking. Bugbee wants to visit one of his favorite ridges.

It’s a long, hard scramble up a steep scree slope, followed by a plunging descent into a canyon, and then a longer climb up a steeper scree slope. This is how El Jefe travels through the mountains, as Bugbee learned the hard way. “To get my cameras in the right place, I had to stop thinking like a human, and start thinking like a jaguar,” he says. “Humans travel in the canyons, because it’s easier, but he’ll just blast up the canyon wall and over the ridge, taking the most direct route.”

Scrabbling up the loose scree, bushwhacking through lacerating thickets of oak and manzanita, we disturb two rattlesnakes who coil and buzz. Piles of fresh bear scat are littered around. Overhead, red-tailed hawks and golden eagles soar across a vast blue sky. Finally we reach a high slope under a rock outcropping that looks like a castle. “The first time we came here, Mayke found five of his scats,” says Bugbee. “I backed off and stayed away.”

Mayke leads us to the bleaching bones of a torn-apart bear carcass. Bugbee picks up the skull. The front is crushed, and the back is punctured in four places, perhaps by jaguar teeth. “This is a really interesting find,” he says. “It looks like a jaguar kill, but there are no records of jaguars killing black bears.” Then Bugbee finds some whitish dried-up scat, far too old to hold a scent. “It looks like jaguar scat,” he says, “and those look like bear hairs in the scat.”

He puts the scat and the skull into zip-lock bags and outlines a likely scenario. “A young adult bear is foraging around, El Jefe explodes from ambush, knocks him on his ass, crushes his skull, and then feeds on him. But we need to test the scat. It could be mountain lion. Those hairs might not be bear.”

From this high vantage point, El Jefe could see all the way south into Mexico; the northern ranges of the Sierra Madre cordillera are a blue silhouette on the horizon. Jaguars have a highly developed spatial memory, so El Jefe knows where he came from, and that other jaguars are there, including females.

Below us to the northeast is the proposed site of the Rosemont Mine. If its permits are approved, the mile-wide, half-mile-deep pit will be dynamited in the foothills. Trucks generating 50 round-trip shipments a day will haul off the copper concentrate. More than a billion tons of waste rock will be placed in engineered structures at least one mile away from the mountains, right by the only two places in the nation where jaguar and ocelot have been photographed in the same location.

A USFWS study indicates that 12 endangered and threatened species would be affected by the mine, including the Chiricahua leopard frog, the Southwestern willow flycatcher, three fish species and the northern Mexican garter snake. “The mine will pump out millions of gallons of water, drying up springs and creeks, contaminating groundwater,” says Bugbee. “In arid country like this, that’s the most devastating thing of all.”

**********

In April 2016, the USFWS issued its long-awaited “final biological opinion” on the Rosemont Mine. Overturning its own scientists, who stated that the mine would kill or harm El Jefe and other endangered species, the agency found no reason under the Endangered Species Act to prevent construction.

Steve Spangle, the regional supervisor, says Hudbay has offered “substantial conservation measures” to mitigate the impact of the mine, including the purchase and preservation for wildlife of 4,800 acres near the mine. Hudbay’s director of communications, Scott Brubacher, stresses that mining in the U.S. is tightly regulated to minimize environmental impact. “We present a proposal to the regulatory agencies,” he says. “They’re the ones that decide if the mine is built.”

Patrick Merrin, a Hudbay vice president, points out that copper is an essential component in electronics, electrical transmission and everyday life. “The average American child born today will use 1,700 pounds of copper in a lifetime,” he says. “Where’s it going to come from?”

Jaguars and other endangered animals will be negatively affected by the mine, Steve Spangle acknowledges, but it won’t put the survival of their species in jeopardy. “There are viable populations in other locations,” he says. “If there’s a jaguar in the Santa Ritas and they start building the mine, he’ll probably be displaced and go south.”

Spangle also wants to correct a widespread misapprehension about his agency. “We don’t approve mines. We just review projects for compliance with the Endangered Species Act. We used the best available science and computer models to make this determination on the Rosemont Mine.”

Bugbee is disappointed but not surprised by U.S. Fish and Wildlife’s decision; in the last seven years, examining more than 6,000 projects across the nation for their impact on wildlife, the agency has not ruled against any of them. Randy Serraglio, from the Center for Biological Diversity, has filed notice to sue, challenging the final biological opinion on the Rosemont Mine. “The land has been designated as critical jaguar habitat, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife has a legal obligation under the Endangered Species Act to protect it,” he says. If USFWS prevails in the courts, the mine will then need a water permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and a final permit from the U.S. Forest Service. (As this article went to press, the Los Angeles regional office of the Corps recommended denial of the project; a final decision has not been made.)

If the permits are approved, it seems certain that the mine will be built, but not any time soon. The global copper industry is a boom-and-bust business, and at present it’s going through a bad slump. “Sooner or later, the price of copper will pick up again, and if the permits are there, Hudbay or some other company is going to dig that fortune out of the ground, with a devastating impact on wildlife,” says Serraglio.

**********

The Bugbee-Neils house on the edge of Tucson is home to five dogs, three cats, 40 baby tortoises, various chickens and turkeys, a prairie dog, a cockatoo and a roomful of snakes. Bugbee was a herpetologist until he fell under El Jefe’s spell.

Removing the bear skull from its zip-lock bag, he shows it to Neils, an expert on black bears from her years studying them in Florida. “This was a young adult female about 230 pounds,” she says. Bugbee then removes the suspected jaguar scat, spritzes it with water, and reseals it in the plastic bag. He waits for an hour and then hides the moistened scat among the cactuses in the front yard. Then he fetches Mayke from her kennel and gives her the command, “Find the scat! Find the scat!”

Mayke systematically searches the yard, zigzagging back and forth with her nose to the ground, until a breeze gets up and wafts the scent toward her. She trots directly to the scat, sniffs it, sits down, looks at Bugbee and barks twice.

“It’s jaguar!” exclaims Neils. The hairs in the scat are later confirmed in the lab as black bear. This is the first recorded predation by a jaguar on a black bear, and as Neils points out, it occurred where the northern limit of the jaguar’s range reached the southern limit of the black bear’s range. “It was north against south, and south won.”

Bugbee sits down at his laptop, and finds the last photographs and videos of El Jefe. Where is he now? He could have been shot, or killed by a vehicle. An injury could have lessened his hunting powers, leading to death by starvation. He could be in another Sky Island mountain range. There have been rumors and several unconfirmed sightings of a jaguar in the Patagonia Mountains, not far from the Santa Ritas. It could be El Jefe, or the next young dispersing male from Mexico.

“I think he’s gone back to Mexico,” says Bugbee. “Take a look at this.” He clicks open the last photograph of El Jefe, and zooms in to show his swollen testicles. “They are huge, as big as his paws, and in the last video, he’s acting antsy, like he can’t stand it anymore. He has everything he needs in the Santa Ritas except a female.”

Macho B would disappear into Mexico for long periods of time, presumably to mate. Once he was gone for eight months, and then returned to his old haunts in southern Arizona. El Jefe might be doing the same thing and show up again in the Santa Ritas any day now. “Without a radio collar, we simply don’t know,” says Bugbee. “I hope he comes back, just for personal reasons. It would make me very happy indeed.”

Editor's note, November 21, 2016: An earlier version of this story said that trucks "generating anywhere from 55 to 88 round-trip shipments a day will haul off the ore” from the proposed Rosemont Mine. In fact, copper concentrate will be hauled off in 50 daily shipments. We also said that “more than a billion tons of toxic mine waste will be dumped against the mountains.” In fact, the waste rock will be placed in engineered structures at least one mile away from the mountain. Both storm water runoff and ground water at the site must meet Arizona water quality standards.

Related Reads

An Indomitable Beast: The Remarkable Journey of the Jaguar

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/24/90/249097ea-960d-4688-9d09-8c1ae9663753/oct2016_e17_jaguar.jpg)