Rising Seas Endanger Wetland Wildlife

For scientists in a remote corner of coastal North Carolina, ignoring global warming is not an option

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/planting-salt-tolerant-trees-631.jpg)

When a buttermilk moon rises over Alligator River, listen for red wolves. It’s the only spot in the world where they still howl in the wild. Finer boned than gray wolves, with foxier coloring and a floating gait, they once roamed North America from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico. By the mid-1970s, because of overhunting and habitat loss, just a few survived. Biologists captured 17 and bred them in captivity, and in 1987 released four pairs in North Carolina’s Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge.

Today more than 100 red wolves inhabit the refuge and the surrounding peninsula—the world’s first successful wolf reintroduction, eight years ahead of the better-known gray wolf project in Yellowstone National Park. The densely vegetated Carolina refuge is perfect for red wolves: full of prey such as white-tailed deer and raccoons and practically devoid of people.

Perfect, except it may all be underwater soon.

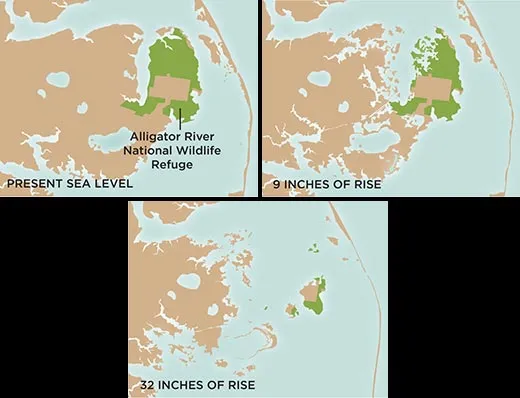

Coastal North Carolina is more vulnerable than almost anywhere else in the United States to sea-level rise associated with climate change, and the 154,000-acre Alligator River refuge could be one of the first areas to go under. A stone’s throw from Roanoke Island, where the first English colony in North America was established in the 1580s, it’s a vibrant green mosaic of forest, piney swamp and salt marsh. I’ve seen a ten-foot alligator dreaming on a raft of weeds, hundreds of swallowtail butterflies rising up in giddy yellow spirals and scores of sunbathing turtles. The refuge has one of the highest concentrations of black bears on the East Coast. It is home to bobcats and otter and a haven for birds, from great blue herons to warblers to tundra swans. Most of it lies only about a foot above sea level.

Scientists at Alligator River are now engaged in a pioneering effort to help the ecosystem survive. Their idea is to help shift the entire habitat—shrubby bogs, red wolves, bears and all—gradually inland, while using simple wetland-restoration techniques to guard against higher tides and catastrophic storms. At a time when many coastal U.S. communities are paralyzed by debate and hard choices, such decisive action is unusual, if not unique.

“We’re on the front line here,” says Brian Boutin, a Nature Conservancy biologist leading the Alligator River adaptation project. “We’re going to fight [sea-level rise] regardless. But it matters whether we fight smart or fight dumb.”

Sea level has been increasing since the peak of the last ice age 20,000 years ago, when the glaciers began melting. The rise happens in fits and starts; in the Middle Ages, for instance, a 300-year warming period sped it up slightly; starting in the 1600s, the “Little Ice Age” slowed it down for centuries. But scientists believe that the rate of rise was essentially the same for several thousand years: about one millimeter per year.

Since the Industrial Revolution, however, the burning of fossil fuels has increased the amount of carbon dioxide and other gases in the atmosphere, which trap the earth’s reflected heat—the now familiar scenario called the greenhouse effect, the cause of global warming. The rate of sea-level rise around the world has tripled over the past century to an average of about three millimeters a year, just over a tenth of an inch, because of both melting glaciers and the expansion of water as it warms.

In 2007, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicted seven inches to two feet of global sea-level rise by 2100. Some scientists, however, think it will be more like six feet. Such wildly varying predictions are the result of huge unknowns. How much of the gargantuan ice sheets in Greenland and West Antarctica will melt? How will human populations affect greenhouse gas emissions? Will ocean currents change? Will the water rise steadily or in spurts?

Making matters worse, the mid-Atlantic region lies on a section of the earth’s crust that is sinking one or two millimeters a year. In the last ice age, the continental plate on which the region sits bulged upward like a balloon as massive glaciers weighed down the plate’s other end, in what is now the Great Lakes region. Ever since the glaciers began to melt, the mid-Atlantic has been falling back into place. The inexorable drop compounds the effects of sea-level rise.

Taking all the data into account, a panel of North Carolina scientists told the state this past spring to prepare for a three-foot rise by 2100, though some regional experts think that estimate is low. (The only places in North America more imperiled are the Mississippi River delta, the Florida Keys and the Everglades.)

Moreover, as the ocean surface warms, some experts predict that stronger storms will hit the Atlantic Seaboard. A major hurricane could bring extreme tides and crashing waves, which can make short work of a wetland. In 2003, scientists in Louisiana predicted that the state stood to lose 700 square miles of wetlands by 2050. Two years later, during hurricanes Katrina and Rita, 217 square miles vanished practically overnight.

Already at Alligator River, salty water from the surrounding estuaries is washing farther inland, poisoning the soil, Boutin says. The salt invasion triggers a cascade of ecological change. The pond pines turn brown and the dying forest is overrun by shrubs, which themselves wither into a dead gray haze. A salt marsh takes over, until it, too, is transformed, first into little jigsaw pieces of land and finally into open water.

Boutin says his team has a decade or less to act. “If we don’t stop the damage now, it’s all going to start crumbling,” he says. “We don’t want the transition to open water to happen so quickly that the species that depend on the land don’t have enough time.” Sea walls and other traditional engineering techniques aren’t an option, he says, because sheltering one portion of coast can speed erosion in another or choke the surrounding wetlands.

Healthy wetlands can keep up with normal sea-level fluctuation. They trap sediment and make their own soil by collecting organic matter from decomposing marsh plants. Wetlands thereby increase their elevation and can even slowly migrate inland as the water rises. But the wetlands can’t adapt if the seawater moves in faster than they can make soil.

The Alligator River project aims to buy time for the ecosystem to retreat intact. Boutin and co-workers hope to create migration corridors—passages for wildlife—connecting the refuge with inland conservation areas. But the relocation of plants and animals must be gradual, Boutin says, lest there be a “catastrophic loss of biodiversity.”

Boutin drives me in a pickup truck to the edge of a vast marsh full of salt meadow hay and black needle rush. Small waves smack the shore. In the distance, across Croatan Sound, we can see the low-slung island of Roanoke. This is Point Peter, the project’s testing ground.

Like many East Coast swamps, Alligator River is crisscrossed with man-made drainage ditches. Workers will plug some of those ditches or outfit them with gates, to keep the saltwater back at least awhile.

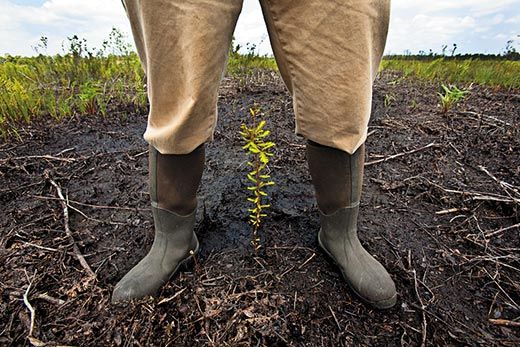

There are 40 acres of newly planted saplings—native bald cypress and black gum, which are salt- and flood-tolerant—intended to keep the forest in place a bit longer as the sea level rises. Wolves, bears and other animals depend on the forest, and “we’re holding the line to allow them to use the corridors” to get to higher ground, Boutin says.

Out in the water, white poles stake the outline of an artificial reef that is scheduled to be built soon. Made of limestone rock poured from a barge, the reef will attract oysters and shield the marsh edge from violent waves. This living buffer will also cleanse the water and create habitats for other marine animals, increasing the marsh’s resilience. In other places, the scientists will restore aquatic plants and remove invasive grasses.

The biologists are evaluating their efforts by counting oysters and fish, testing water quality and, with aerial photography, assessing erosion. If successful, the project will be replicated elsewhere in the refuge, and maybe, the scientists hope, up and down the East Coast.

“The next generation may say ‘Wow, they did it all wrong,’” says Dennis Stewart, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist working on the project. But, he adds, “I would rather future generations look back and say, ‘Well, they tried to do something,’ rather than ‘They just sat around.’ We got tired of talking and decided to do something about this.”

One spring day, David Rabon, the USFWS red wolf recovery coordinator, takes me along with his tracking team to look for new pups belonging to a group called the Milltail Pack. The shady forest, crocheted with spider webs, is remarkably peaceful, the sunlit leaves like green stained glass. I hang back until a sharp whistle cracks the silence: the trackers have found the den, a cozy nook beneath a fallen tree, in which seven velveteen beings squirm and mewl toothlessly. Fourth-generation wild wolves, they are about 6 days old.

Their den will probably be submerged one day. The land that was the red wolves’ second chance at wildness will likely become a windblown bay. But if the climate adaptation project succeeds, and future generations of red wolves reach higher ground a few miles to the west, packs may once again prowl a verdant coastline, perhaps even a place reminiscent of Alligator River.

Abigail Tucker is a staff writer. Lynda Richardson shot Venus flytraps for Smithsonian.

Editor's note: An earlier version of this article misidentified a tree as a bald Cyprus. This version has been corrected.