Robotics Can Get Girls Into STEM, but Some Still Need Convincing

The lack of women leaders in STEM creates “a catch-22 death spiral.” Robotics teams try to change that

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/97/6e/976e9d3f-c5a7-4a03-8c85-36e6baec2bbe/girlsrobot.jpg)

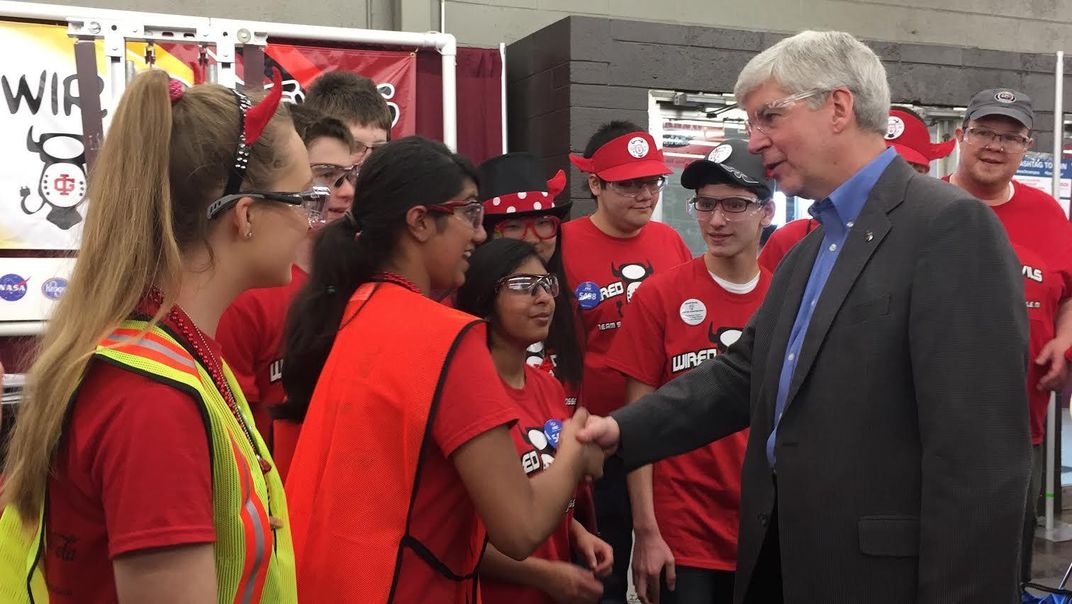

When her high school in Grosse Ile, Michigan, started a co-ed robotics team dubbed The Wired Devils, Maya Pandya thought she’d give it a try. The 17-year-old already excelled in math and science, and had considered going into engineering as a career. But while the team was part of a larger initiative meant to “inspire young people’s interest and participation in science and technology,” her first interactions with other team members left her frustrated.

“When I first walked in, the guys on the team acted like I didn’t really want to do engineering,” says Maya, who will be a senior next year. “It felt like they assumed things automatically. Once I pushed people out of that mindset, they accepted me and started listening to my ideas.”

It wasn’t until the last few weeks of the team’s 6-week build session, when students came together to construct a robot for an upcoming competition, that things seemed to click. Maya recalls working on her team’s robot one day, and realized that hours had passed. “I was enjoying it so much that time just flew by,” she says. “It was that moment that I realized I could actually go into robotics.”

Maya is part of a growing number of girls who are trying out robotics—through school clubs or regional organizations, and in co-ed or all girls teams—and finding out that they have a knack for it. FIRST (For Inspiration & Recognition of Science & Technology), the nonprofit that helped spark the girls-in-robotics moment and is behind The Wired Devils, now boasts more than 3,100 teams nationwide and over 78,000 student-aged participants.

Robotics advocates say these programs provide a way for school-age girls to get exposure to the field while also discovering their passion for STEM-based careers—a priority that’s been on the national agenda for the past several years, in part thanks to President Obama’s push for increased participation by women and minorities in STEM careers.

“There's a push overall for kids to be into robotics because, from a talent pool standpoint, the U.S. isn't putting out enough people to stay ahead in math, science, or any of the STEM fields,” says Jenny Young, founder of the Brooklyn Robot Foundry, a robot-based after-school program that strives “to empower kids through building.” “Girls are half the population, and there really isn't any reason why girls shouldn't see how fun and exciting and rewarding engineering can be.”

Others say the rise of girls in robotics reflects a natural transition as the gender divide begins to narrow. “I have seen a shift in society over the last year of basically ‘girl power’ and the removal of gender barriers,” says Sarah Brooks, program manager for the National Robotics League, a student robot-building program run by the National Tooling & Machining Association. “It has allowed more girls to feel confident in these types of roles—and it has allowed the boys to be confident that the girls are there.”

Of course, robotics isn’t just about STEM training. It's also a lot of fun. “Robotics are amazing,” says Maya’s younger sister Keena, 15, who has also been bitten by the robotics bug. “At first I only joined the club because my sister was involved. But once I got into it and I started seeing the design process, the build process, the programming and how everything came together, I found out that this is a field that I could possibly go into.”

Arushi Bandi, an incoming high school senior at Pine-Richland High School, says that robotics programs helped her get key mentorship from other girls. Bandi, who is 16, is a member of Girls of Steel, a girls-only high school robotics team run by Carnegie Mellon University. Thanks to advice from older team members, Bandi realized that she was interested in majoring in computer science—a marriage of subjects and interests she was already drawn to—when she attends college. Before, she hadn’t even known the field existed.

Yet while the raw numbers of girls (and boys) participating in robotics is increasing, a gaping gender disparity is still apparent. In Michigan there has been an “uptick” in female robotics participation, but the percentages are less than inspiring. During the 2012-2013 school year, 528 of the 3,851 students enrolled in these programs were female (14 percent), while in 2014-2015, 812 out of 5,361 were female (15 percent), according to statistics compiled by the Michigan Department of Education.

With the White House STEM push and programs like FIRST, there isn't necessarily the same lack of opportunities for young women to get into robotics and STEM careers as there once was. The problem, it appears, is often the lack of suitable role models. “I think the challenge is getting women into those fields,” says Bandi. “And, after that, future generations will naturally transition into them.”

Terah Lyons, a policy advisor in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, agrees. Lyons points to the striking decline in the number of undergraduate degrees earned by women in engineering, math/statistics and—most dramatically—computer science over the past few years. Degrees earned by women have dropped from 28 percent in 2000 to just 18 percent in 2012, the National Science Foundation reported in its 2014 Science and Engineering Indicators Report.

“It’s tough to envision yourself as a leader in a field if you don’t see leaders that resemble you,” says Lyons. “The fact that there aren’t sufficient female role models is a catch-22 death spiral in a way, because it discourages women to go into these STEM fields and, further, women in future generations aren’t encouraged to study the subjects and the decline sort of happens from there.”

As Maya's experience shows, girls interested in entering robotics still face cultural barriers—which the girls themselves are often very aware of. “In our society, a lot of the toys for boys are more focused on building,” says Maya. “Girls really don't have that. When girls join robotics, they get exposed to all of these things.”

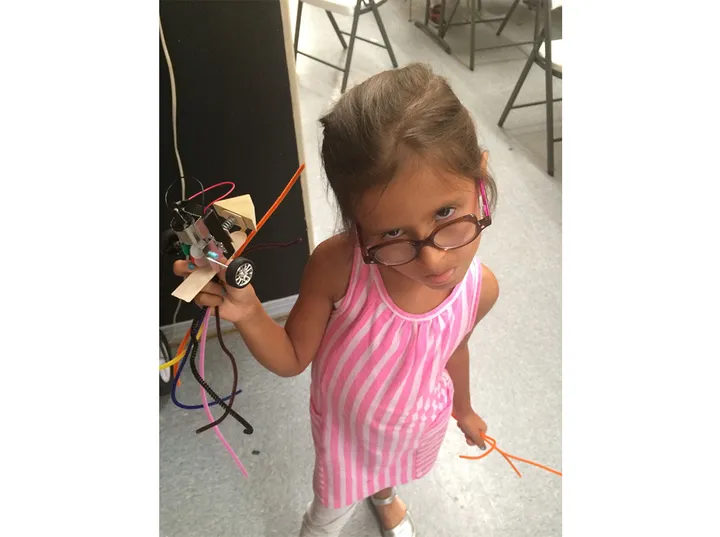

Young, a mechanical engineer, says making robots fun will help pull more kids into the fold, particularly young girls who may not be engaged the same way as their male peers. She strives counter the societal stereotyping that “robots are just for boys” by teaching simple circuits to build basic robots, but letting the kids decide what to do next. Some of her students build fuzzy pink kitties that “wiggle and wobble,” while others craft more boxy, classically-shaped robots—it’s up to them.

This fall, young girls around the country will watch as our country’s first female presidential nominee campaigns for the highest position in the United States. But the numbers show that overcoming the gender hurdle and encouraging women to go into science and math will still require time and dramatic societal reprogramming. “We need to tell the younger girls who are interested in these fields that they’re good at it,” says Young. “If girls and robotics could be mainstream, that would be the sweetest day ever.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kristen_A._Schmitt.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kristen_A._Schmitt.jpg)