The Science Behind Florida’s Sinkhole Epidemic

Reports of these ground-chasms have been swelling in the past few years. Geology helps explain why

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1e/f9/1ef91709-a3fb-43f8-bc02-07cfea34a574/ca77w9.jpg)

There are many good reasons why The Villages is known as “Disney for Seniors.”

The largest retirement community in the world, The Villages is also one of America’s safest and most leisurely places to live. Sumter County, populated almost entirely by Villagers, is 62nd among 67 counties in Florida for violent crime—likely because the median age is 66.6, the oldest of any U.S. county. The ubiquity of gates, guard booths and mandatory visitor I.D. cards lends to the low crime. Vehicular deaths are very low, which makes sense given that Villagers commute in golf carts more than cars. The Villages is also located in the safest area of Florida for hurricanes.

But Villagers are increasingly fearful of a growing, surreal threat: the ground suddenly opening up and swallowing them whole.

“Everybody is worried,” a 10-year resident of the Village of Calumet Grove told me this March, pointing to a saucer-sized hole at his curb where sinkhole specialists drilled to check for weak spots. A month earlier, in mid-February, seven sinkholes opened across the street and into a golf course, forming a zig-zag crack across the facade of one house and causing four homes to evacuate. One is now condemned. A town hall that week attracted five times more Villagers than usual. “It’s not a good time to sell,” the elderly neighbor says, with a weary laugh. (He asked me not to use his name.)

In contrast to its otherwise serene status, The Villages is a hotbed of sinkholes. They occur more frequently in Florida than any other state, though this week we've seen them appear on Maryland roads and even in front of the White House. And The Villages is smack in the middle of Sinkhole Alley—a swath of counties in Central Florida that carry the greatest risk. (A German bakery near The Villages even sells a popular pastry called the Sinkhole.)

Typically sinkholes are no more than a headache for property owners, but when tragedy does strike, it’s the stuff of nightmares. Among the six recorded deaths from sinkholes in Florida history is Jeffrey Bush, who was sleeping in his bedroom when a sinkhole sucked him 20 feet underground. His body was never recovered.

The number of reported sinkholes in The Villages has spiked in recent years. An official with The Villages Public Safety Department told the Orlando Sentinel that residents had reported “several” sinkholes in 2016, though none affecting homes—an assessment matched by the archives of Villages-News. Ditto for 2015; in 2014 three sinkholes affected six homes.

In 2017, by stark contrast, at least 32 sinkholes were reported by that independent news site. At least eight homes were affected, plus a country club, a busy intersection, a Lowe's home improvement store, and the local American Legion post, the largest in the world. (The Daily Sun, a large newspaper owned by The Villages’ developer, reported on none of them except the one at the busy intersection, only to say the hole was “later determined not likely” a sinkhole.) In just the first three months of 2018, at least 11 sinkholes were reported by Villages-News, affecting eight homes—all before sinkhole season even started, in early spring. Four more sinkholes sprang up this week.

That there’s such a thing as “sinkhole season,” just as there’s a “tornado season” and “hurricane season,” speaks to the many factors that contribute to the threat. Underlying all of them is the fact that Florida is built on a bedrock of carbonate, primarily limestone. That rock dissolves relatively easily in rainwater, which becomes acidic as it seeps through the soil. The resulting terrain, called “karst,” is honeycombed with cavities. When a cavity becomes too big to support its ceiling, it suddenly gives way, collapsing the clay and sand above to leave a cavernous hole at the surface.

The main trigger for sinkholes is water—too much of it, or too little. The normally moist soil of Florida has a stabilizing effect on karst. But during a drought, cavities that were supported by groundwater empty out and become unstable. During a heavy rainstorm, the weight of pooled water can strain the soil, and the sudden influx of groundwater can wash out cavities. Central Florida was in a severe drought at the beginning of 2017, followed by the intense rainfall of Hurricane Irma that hit The Villages in September—and a deluge after a drought is the optimal condition for a sinkhole outbreak.

But those major events from Mother Nature in 2017 don’t account for the spate of sinkholes this year already. The weather in Sumter County has been pretty typical. So what’s going on?

Man-made development, it turns out, is the most persistent factor for increased sinkholes. Earth-moving equipment scrapes away protective layers of soil; parking lots and paved roads divert rainwater to new infiltration points; the weight of new buildings presses down on weak spots; buried infrastructure can lead to leaking pipes; and, perhaps most of all, the pumping of groundwater disrupts the delicate water table that keeps the karst stable. “Our preliminary research indicates that the risk of sinkholes is 11 times greater in developed areas than undeveloped ones,” says George Veni, the executive director of the National Cave and Karst Research Institute who conducted a field study in Sinkhole Alley.

And The Villages has been in development overdrive. It was the fastest growing metropolitan area in the US. four years in a row (2013-16), and it’s still in the top 10. In his 2008 book Leisureville, journalist Andrew Blechman reported that The Villages would “finish its build-out—an industry term for the point when a project is complete—in the very near future,” peaking at “110,000 residents.” Yet a decade later, the population has sped past 125,000. Last year The Villages reported a 93 percent boom in housing construction and a new purchase of land that will yield up to 20,000 homes. Another land deal for 8,000 new homes is nearing completion.

Those new homes will bring more golf courses, and The Villages already has 49 of them (#2 per capita among all U.S. counties). The retention ponds built on those courses can leak into the karst and trigger sinkholes. Irrigating those 49 courses and the tens of thousands of lawns in The Villages is also a significant risk factor. In his 2016 book Oh, Florida, veteran reporter Craig Pittman reveals how his friend who worked at the Daily Sun said the staff was never to write two things: 1) anything complimentary of Barack Obama, and 2) “The numerous sinkholes that open up because of all the water being pumped from the aquifer to keep lawns and golf courses green.”

In a scathing column, Orlando Sentinel’s Lauren Ritchie notes how the fledgling community in 1991 had a water permit to use 65 millions gallons a year, but by 2017 that rate reached “a stunning 12.4 billion gallons a year.” The local aquifer in Sumter County is also threatened by a controversial plan by a bottling company to pump nearly a half-million gallons of water a day—and double that rate during peak months. Despite the protests of Villagers worried that a falling water table will spur sinkholes, pumping will begin soon.

.....

The Villages shouldn't be singled out when it comes to sinkholes. Marion and Lake, the two counties that The Villages pokes into, are #4 and #10, respectively, on RiskMeter’s 2011 list of the most sinkhole-prone counties in Florida. Number one is Pasco, which abuts Sumter to the south. Last summer a 260-foot-wide sinkhole yawned underneath a Pasco neighborhood, consuming two homes and condemning seven more, making it the county’s largest in 30 years. That massive chasm rivaled the epic Winter Park sinkhole in Orange County—#8 for RiskMeter, an online tool providing hazard analysis for insurers.

Citrus, directly to the west of Sumter, is both #6 for RiskMeter and the fourth “grayest” county in the U.S., based on the percentage of residents over age 65. Pasco and Marion are also among the top 10 counties nationwide with both a high concentration and high number of older people.

In Ocala, near The Villages, a sinkhole in a fast-food lot swallowed a car and forced the elderly couple inside to crawl out. A man simply standing in the grass in The Villages slipped through a trapdoor of a five-foot hole. In the Village of Glenbrook, a retired couple found a sinkhole literally on their doorstep. Another Villager reported a “prowler” to 911 only to discover a dark void instead. In the nearby city of Apopka, half a couple’s home collapsed and “nearly 50 years of memories sank with it.”

I spoke with geologist and sinkhole expert David Wilshaw on the same day he was returning from a trip to The Villages to inspect a suspected sinkhole. It turned out to be a false alarm—the small depression was caused by a leaking irrigation line—but the shaken resident told Wilshaw she hadn’t slept the whole night, afraid the ground would gobble her up. Injuries from sinkholes are rare, but “perception is everything,” says Wilshaw, “particularly with the elderly population. They’re also fearful they may lose their best investment”—their house—“and lose it during their retirement years,” when they’re most vulnerable.

Central to that fear factor is how unpredictable sinkholes are. They usually form without warning, and it’s difficult to detect weak spots in the ground. “Drilling exploration holes in The Villages is a challenge,” says Wilshaw, “since rock will be 5 feet down in some places and 100 feet down if you move 20 feet to the side.” Wilshaw, who runs his own company specializing in assessing sinkhole risk, is often hired to survey sites using ground penetrating radar (GPR), which is the best way to detect cavities. But he says many homebuilders “will do absolutely nothing and instead rely on the end user” to check for cavities, since Florida law doesn’t require it. “It’s a little bit of the Wild West,” he says.

Can anything besides GPR help predict sinkholes? NASA technology has shown potential: Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) detects subtle changes in ground elevation over time when the sensor is flown repeatedly over an area susceptible to sinkholes, especially the slow-forming ones called “cover-subsidence.” When that use for InSAR emerged in 2014, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) reached out to NASA for help, but when I checked in with a DEP spokesperson, she said that’s not happening anytime soon.

Even when a site is surveyed and deemed safe from sinkholes, one can still form a few years later, given the precarious nature of karst. “It’s best to just cross your fingers and buy insurance," says Wilshaw. But homeowners insurance only covers “catastrophic ground collapse”—when a sinkhole makes a home uninhabitable. Any damage just short of that must be covered by sinkhole insurance, whose deductible in Florida is typically 10 percent of the home’s value.

“Not all homes qualify for [that] broader coverage, which is admittedly a scary proposition in Florida,” according to a front-page article in the May 2018 issue of The Bulletin, published by the Property Owners’ Association (POA) of The Villages. (The group isn’t affiliated with the developer).

Even when a sinkhole is repaired (“remediated” is the technical term), it will sometimes reopen. Perhaps the most dramatic sinkhole to ever hit The Villages, in Buttonwood—just look at this photo—lurched open several months after remediation began. So did the sinkhole that killed Jeffrey Bush.

.....

Conspicuously absent from RiskMeter’s top 10 list is Sumter County. That 2011 list, though, was based on sinkhole insurance claims, and scads of them were falsely reported in the years before 2011, when Florida lawmakers overhauled the abused system. A much better gauge of sinkhole risk followed two years later (just as The Villages was starting its four-year growth streak): The 2013 Hazard Mitigation Plan, created by the Florida Division of Emergency Management (DEM), which assigned Sumter a “medium” risk for sinkholes. Only eight other counties were given a higher level of risk.

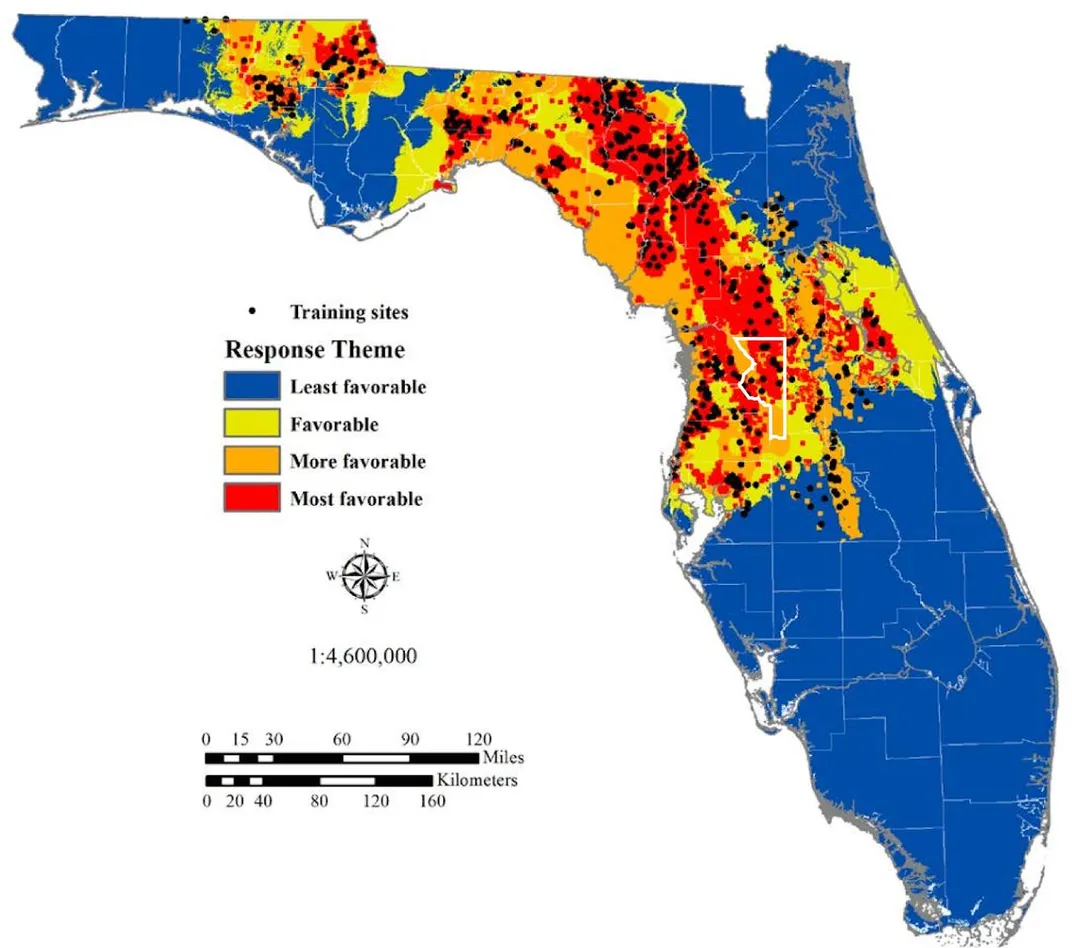

But as DEM acknowledged, that 2013 assessment was “imprecise and poorly substantiated by available geologic data” because it was primarily based on citizen reports of sinkholes unverified by geologists. Enter Clint Kromhout of the Florida Geological Survey: In 2013, he and his team secured more than $1 million in federal funds to travel around Florida verifying those sinkholes and create a predictive map showing which areas have the most “relative vulnerability.” Among the many reporters Kromhout spoke to during the three-year study was Tampa Bay Times’ James L. Rosica, who noted, “The goal for the scale of the state map is at least the county level, but Kromhout said he hopes they will be able to get to a neighborhood-by-neighborhood detail.”

Veni, the karst expert I interviewed, calls Kromhout’s 2017 report “the most detailed, comprehensive analysis of sinkhole risk that I’m aware of.” (Kromhout declined to be interviewed for this story, as did a representative for The Villages.) Its long sought-after predictive map was included in the 2018 Hazard Mitigation Plan that came out in February.

That’s as detailed as the map gets. As the Sinkhole Report states, “Most importantly, the favorability map is not of sufficient detail to provide site specific information regarding sinkhole formation.” The Villages is primarily located in the northern part of Sumter County, which is almost entirely in the red zone.

How helpful is the Sinkhole Report? “I don’t think it is the prediction model that some hoped for (it would be very difficult to create one), but it does advance the science,” says Robert Brinkmann, a geology professor at Hofstra University who wrote Florida Sinkholes: Science and Policy and owns a house in Sinkhole Alley.

“The real challenge here is that the state doesn’t really fund much sinkhole research, particularly since real estate remains one of the driving economic engines in the state,” Brinkmann adds. “The federal government has not really funded any significant studies on the topic except for this modest one. Millions in federal dollars go every year to tsunamis, earthquakes, volcanoes and hurricanes, but little if any goes to studying sinkholes. Certainly [the former] are horrible, but they are one-time dramatic events. Sinkholes are a constant threat and much of the damage happens slowly over time. The annual property damage from sinkholes is staggering”—$300 million is a conservative estimate.

That damage could escalate as climate change intensifies. “As sea level rises in response to climate change, groundwater levels in near-coastal areas will also rise and result in increased flooding of sinkholes,” predicts Veni. “Studies on the potential degree of such flooding and its triggering new sinkhole collapses are just beginning.” He's in the preliminary stages of just such a study with a colleague in Florida.

Some Villagers are tempted to throw in the towel. “When we moved [to the Village of Glenbrook] in 2012 we thought we would be here for the rest of our days,” wrote a member of the "Talk of the Villages" web forum on March 5 after a sinkhole forced his neighbors to evacuate, but “now we’re considering moving again which is the last thing I wanted to do.” (Less than two months later, another eight families would evacuate their homes when a dozen sinkholes appeared in an Ocala neighborhood not far from Glenbrook, making national news.) Another Villager added ominously: “I am dreading when the rainy season starts”—May 27, on average for the area.

But the rainy season came early this year: On May 20, after a week of persistent rain, four sinkholes struck Calumet Grove, the Village that suffered seven sinkholes in February. Thunderstorms are expected to continue thanks to a sub-tropical storm system forming off the coast. One of the residents forced from his home in February, 80-year-old Frank Neumann, spoke to Villages-News. “Prior to Monday’s sinkhole activity, Neumann said he was hoping to have his home repaired and stay in the neighborhood he’s lived in for 14 years—largely because of the friendships he and his wife have formed there,” according to the site. “But as he stood in his front yard looking at the second wave of destruction to strike his property in 95 days, he said he wasn’t so sure that remaining in The Villages was a good idea.”