The Science of Good Chocolate

Meet the sensory scientist who is decoding the terroir of chocolate—and working to safeguard the cacao plant that gives us the sweet dark treat

:focal(2762x1824:2763x1825)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6e/20/6e20cc92-5911-4135-af6d-a7aaac3fba0e/ekt3g9.jpg)

While walking through a dense thatch of cacao trees in Gran Couva, Trinidad, food technologist Darin Sukha crushes a dried cacao leaf in one palm and a fresh one in the other. He inhales deeply, then lifts the leaves toward my nose and asks, “What do you find here?”

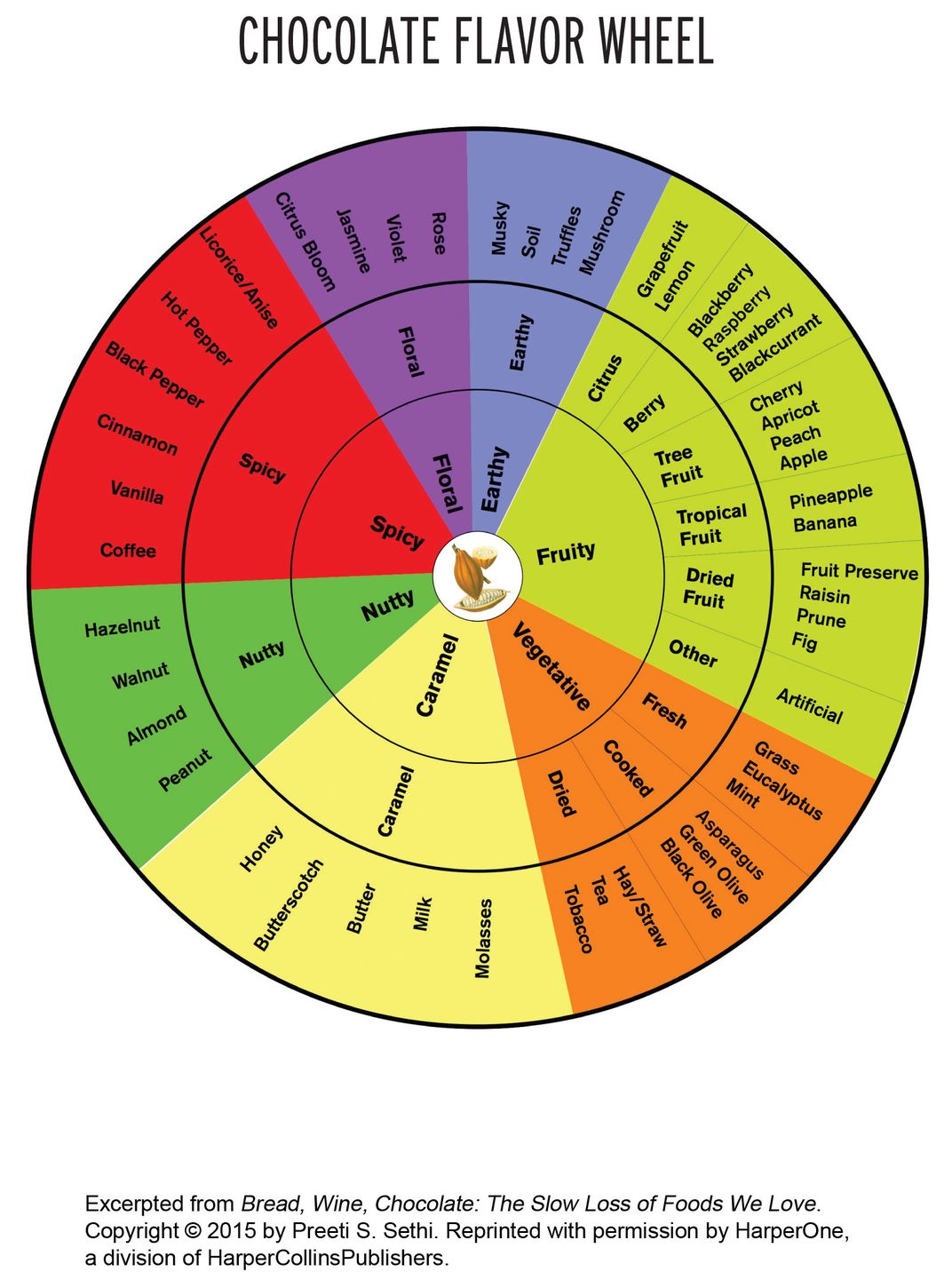

Sukha studies the nuances of smell and taste in the cacao plant, whose pulp-covered seeds, once processed, become cocoa and chocolate. He wants to understand—and relay to chocolate eaters—not only the biological characteristics of the plant, but also the sensorial ones. These references help illuminate a wide variety of flavors inherent in cacao, that, when properly nurtured, will carry over into the final product.

The smell of the dried leaf contains traces of baled hay, while the fresh one offers up bright and vegetal aromas. Both can be found in chocolate. By continuously reaching for more flavor experiences, Sukha says, we can find greater depth in chocolate, a substance that is far more complex than most people realize. “A good piece of chocolate is like a good piece of music. It contains something memorable that stays on your mind for the entire day.”

Most of us don’t recognize this nuance because we grew up on confections characterized by sweetness and one dominant chocolatey note—consistency we expect when reaching for a Hershey's or a handful of M&M’s. But cocoa beans hold a symphony of flavors, from roasted hazelnuts and fresh violets to tart cherries and green apples. These hints exist, to some degree, in all cocoa, but are highlighted in more specialized craft chocolates.

The flavors found within these bars are the result of a range of factors, from soil and climate to microbial activity during the fermentation process. Collectively, these elements make up chocolate’s terroir, something Sukha has been exploring for nearly a quarter-century.

This taste of place is built on the foundational ingredient cacao, a pod-shaped fruit that was domesticated 3,600 years ago. For most of its history, the plant was grouped into three categories loosely based on historical and visual characteristics, but in 2008, a team of geneticists expanded the groupings of cacao to 10. “And every single one of those cocoa beans has a genetic flavor potential,” Sukha says.

Once harvested, the pulp-covered cacao seeds are fermented. Before this process, the seeds are bitter and taste nothing like chocolate. As I describe in Bread, Wine, Chocolate: The Slow Loss of Foods We Love:

Cacao ferments for anywhere from three to eight days, usually heaped under banana leaves or jute sacks, or enclosed in wooden boxes and trays or wicker baskets. The beans are, in essence, cooking, as the pulp around the seeds gets gobbled up by the yeasts that are present in the air and on the surfaces the pulp comes in contact with. [They] convert the sugar in the cacao pulp to ethanol, while bacteria generate lactic acid (the acid that sours milk) and acetic acid (the kind that turns grape juice into wine, then vinegar). The goal is to ensure the cacao is fully cooked so that the astringency and off-flavors that emerge when lactic and acetic acids are formed are eliminated.

BREAD WINE CHOCOLATE

Award-winning journalist Simran Sethi explores the history and cultural importance of our most beloved tastes, paying homage to the ingredients that give us daily pleasure, while providing a thoughtful wake-up call to the homogenization that is threatening the diversity of our food supply.

Through fermentation, the cellular structure of the seed changes and aroma compounds start to develop. Sukha says this process is the biggest driver of flavor. “It’s like adopting a baby, where you can make [a great] impact on the expression of genetic potential.” But by the time a chocolate maker receives cocoa beans, “it can be likened to adopting a teenager, where the personality has been expressed already. All you can do in terms of change is make small tweaks.”

These “tweaks” are roasting, milling and adding ingredients, such as sugar and milk powder, to the cocoa mass.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f1/26/f126b9a9-daa2-4083-8744-6c1defddf1bb/darin_sukha_explaining_fermentation_courtesy_of_darin_sukha.jpg)

“Let’s use an example of a bean that has a very delicate floral note. If that’s the genetic flavor potential, and I don’t ferment those beans properly to reveal [the floral quality], then it will never be expressed. … You have to handle the cocoa understanding what exists.”

Sukha served as lead author of the 2014 paper “The Impact of Processing Location and Growing Environment on Flavor in Cocoa,” the first study to systematically explore how terroir impacts flavor in chocolate. Through years of research, the sensory scientist discovered that fruity flavors in cocoa and chocolate are strongly related to how the beans are fermented, while floral flavors are more closely tied to the genetics of the crop.

As a research fellow at the Cocoa Research Centre (CRC) at the University of the West Indies in St. Augustine, Trinidad, Sukha is not only a chocolate expert, but one of its guardians of biodiversity. The CRC, where Sukha is the head of the Flavour and Quality Section, oversees the largest and most diverse collection of cacao plants in the world. Varieties from the upper Amazon, where the crop originated, through the entire equatorial band where the plants flourish are all grown at a field station known as the International Cocoa Genebank.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/32/9a3240ed-e0c3-4cc8-abb2-4143dbc5fb49/cacao_grown_as_part_of_the_cocoa_research_centre_collection_credit_simran_sethi.jpg)

The collection maintained by the CRC not only holds endless flavor possibilities, but, more importantly, a treasure trove of potential solutions to the challenges facing the crop. Disease and climate change increase the economic hardships facing the six million, mostly smallholder farmers who depend on cocoa for their livelihoods. The wide range of trees grown at the CRC includes varieties that might be more tolerant to drought or resistant to a particular pest. They give scientists the ability to breed traits into the crop to address agricultural challenges today—or in the future.

Sukha is also part of a select global team developing international standards for cocoa quality and sensory analysis. The varieties of cocoa that the group is bringing to the fore are defined as “fine or flavor”—celebrated for genetic diversity and flavors that are intended to be drawn out of the cocoa and highlighted in chocolate.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2b/6d/2b6d59d5-7658-4a09-bad6-1f2e8e7737a9/ecuadorean-cocoa-farmer-alberto-bautista-credit-simran-sethi-.jpg)

In order to sustain the future of chocolate, Sukha says, we have to better value the people who create it. “Our work must come back to what can we do to empower the cocoa producers who wake up every morning and go to their fields.” Otherwise, these farmers—many of whom live in extreme poverty—will turn to other crops or find alternate ways to earn a living.

And that would be a gastronomic loss for the world. “There’s so much behind a good piece of chocolate,” Sukha says. “There’s a backstory … the genetics, the sense of place, the terroir, the tradition, culture and history.”

By having these stories “told and understood and celebrated,” he hopes the market for more diverse chocolates will grow—and the farmers behind the bar will be “fully recognized and rewarded.” Without that compensation and support, the amazing flavors that we’re only just discovering could disappear.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.