A Science Lecture Accidentally Sparked a Global Craze for Yogurt

More than a century ago, a biologist’s remarks set people searching for yogurt as a cure for old age

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e5/6a/e56afd9a-2dcc-45d2-9e02-729c19f7b1bb/istock_000077034147_large.jpg)

In the spring of 1905, Parisians rushed in droves to a newly opened shop off a resplendent grand boulevard near Théâtre du Vaudeville. They weren’t heading there to buy croissants or Camembert, but for pots of yogurt that they believed could prevent aging. At that time, a mania for yogurt was rapidly unfolding on both sides of the Atlantic, and its source was unexpected—a Russian-born biologist who would go on to receive a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Elie Metchnikoff, of the Pasteur Institute, had inadvertently launched the yogurt rush when he claimed in a public lecture, “Old Age,” on June 8, 1904, that aging was caused by harmful bacteria inhabiting the intestines. He urged his audience to boil fruit and vegetables and otherwise prevent noxious bacteria from entering the body. Moreover, he argued, beneficial bacteria had to be cultivated in the intestines, and this was best done by eating yogurt or other types of sour milk.

Metchnikoff and his assistants had shown that sour milk didn’t spoil because of its acidity: In their experiments, microbes converted milk sugar into lactic acid, which, in turn, killed rot-causing germs in a laboratory dish. He speculated that if these microbes produced the same acidity in the human intestine, they might halt the “intestinal putrefaction” he believed precipitated aging. The best candidate, to his mind, was the so-called Bulgarian bacillus, a bacterium found in yogurt from Bulgaria.

“Interestingly, this microbe is found in the sour milk consumed in large amounts by the Bulgarians in a region well-known for the longevity of its inhabitants,” he said in his lecture, delivered in Paris. “There is therefore reason to suppose that introducing Bulgarian sour milk into the diet can reduce the harmful effect of the intestinal flora.”

The following day, the lecture was front-page news and the talk of Paris. Metchnikoff had presented his ideas as a hypothesis, but all his caveats were edited out of euphoric press reports. “Those of you, pretty ladies and brilliant gentlemen, who don’t want to age or die, here’s the precious recipe: eat yaghourt!” suggested the popular French daily Le Temps.

The message soon spread beyond the French borders. In England, Pall Mall Magazine ran an interview with Metchnikoff under the headline “Can Old Age Be Cured?” And in the United States, the Chicago Daily Tribune announced in an article headlined “Sour Milk Is Elixir: Secret of Long Life Discovered by Prof. Metchnikoff,” that “any one desiring to attain a ripe old age is recommended by Prof. Metchnikoff to follow the examples of the Bulgarians who are noted for their longevity, and who consume large quantities of this cheap and easily obtained beverage.”

Soon, ads in Le Figaro invited the public “to taste the delicious Bulgarian curdled milk that the illustrious Professor Metchnikoff has recommended for suppressing the disastrous effects of old age,” sending Parisians to that shop near Théâtre du Vaudeville.

Unable to answer the barrages of letters asking him for information about the new elixir of youth, Metchnikoff published a brochure in the fall of 1905, in which he tried to counter the sensational claims. “Clearly, we do not look upon the milk microbes as an elixir of longevity or a remedy against aging,” he wrote. “This question will be resolved only in a more or less distant future.”

It was too late. The cautionary statement couldn’t quench the soaring thirst for sour milk. Being cheap and safe, it had a compelling advantage over other historic life-extension methods, such as gold-containing powders swallowed by a Chinese emperor in search of immortality or the blood transfusions attempted for rejuvenation in the court of Louis XIV.

Preserving milk by souring has been practiced since antiquity in many warm regions of the world. The taste and texture of the end product depend on the bacteria used, and, if the cultures contain yeast that ferments part of the milk sugar into alcohol, sour milk can even be alcoholic. In the late 19th century, ads occasionally touted such fermented products as koumiss, a drink from the steppes of Central Asia made from mares’ milk, as nourishment for people with tuberculosis and other wasting diseases. Most western Europeans and Americans, though, encountered such milks only during exotic travels. “If a man cannot reconcile himself to sour milk, he is not fit for the Caucasus,” a British mountaineer warned in an 1896 book about the region.

But Metchnikoff’s lecture sparked an extraordinary demand for milk-souring bacterial cultures. Doctors from around the world telegraphed the Pasteur Institute or even personally traveled to Paris in search of the sour stuff. Among the latter was an American with a bushy mustache who ran a sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan, in which he advocated his own version of healthy living based on a vegetarian diet, exercise and sexual abstinence—John Harvey Kellogg, of cornflakes fame. Impressed by the pitcher of sour milk he saw on Metchnikoff’s desk, Kellogg later made sure each of his own patients received a pint of yogurt, writing in his book Autointoxication that Metchnikoff had “placed the whole world under obligation to him in his discovery that the flora of the human intestine needs changing.”

Doctors everywhere started prescribing sour milk—also referred to as “butter-milk,” “Oriental curdled milk” or “yoghourt” in various variants of spelling—for anything from gonorrhea to gum disease. They gave it to patients to help prevent gout, rheumatism and the clogging of arteries. A medical review in Great Britain titled “On the Use of Soured Milk in the Treatment of Some Forms of Chronic Ill-Health” even recommended giving patients sour milk in preparation for surgery, as a disinfectant of the digestive tract.

And as with every remedy, doctors warned about side effects. “It may be well to direct the attention of those who wish to try this sour-milk treatment to the fact that they should assure themselves beforehand that they are fit subjects for it, and they should therefore consult a medical man,” the Lancet cautioned. The British Medical Journal chimed in, “Yoghourt can be used for an indefinite time without harmful results if the dose be not too large, [2.2 pounds] a day should not customarily be exceeded.”

Physicians did occasionally level severe criticism on the promise of life extension that fueled the ongoing hysteria among the general public. Foods and Their Adulteration, an authoritative book published in Philadelphia, added to its 1907 edition a new section, “Sour Milk and Longevity,” in which the author, Harvey W. Wiley, tried to dispel yogurt’s longevity mystique. Excessive claims, he wrote, “only serve to bring the whole subject of the use of sour milk into deserved contempt.” But the easy recipe for longevity was too alluring to be abandoned quickly.

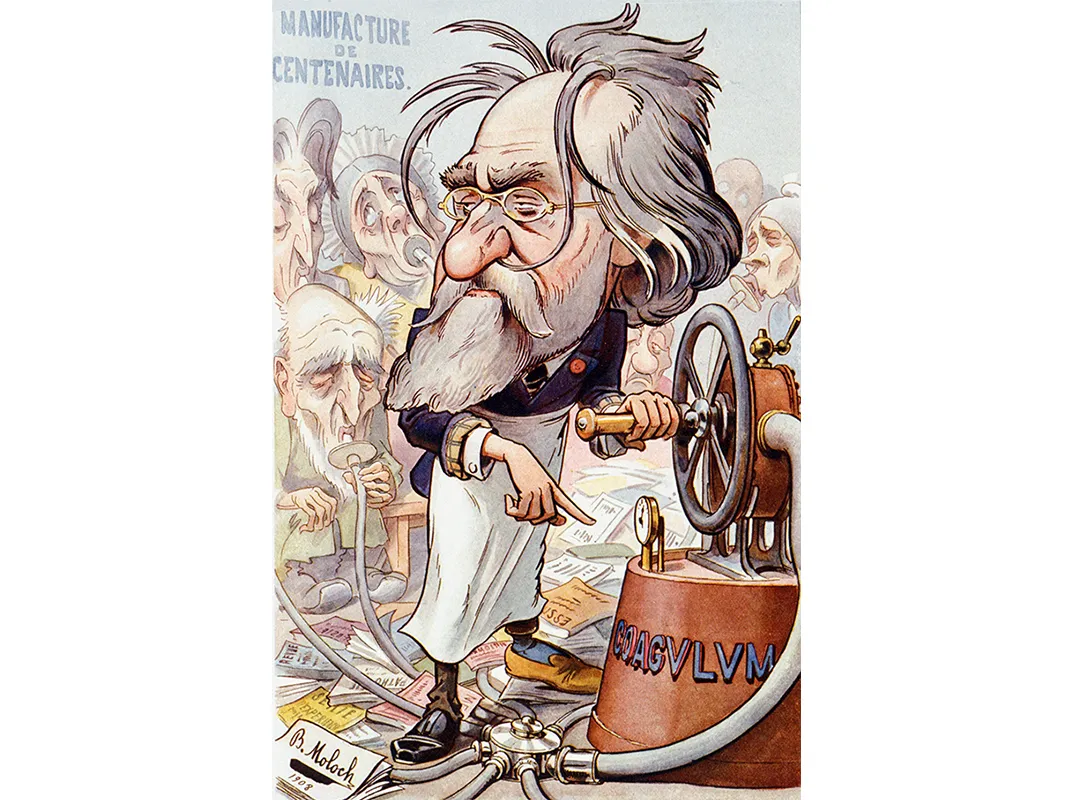

When Metchnikoff received a Nobel Prize in 1908—for pioneering research on immunity he had conducted for some two decades before taking on aging—yogurt’s appeal only grew. Besides, Metchnikoff further ignited everyone’s imagination by arguing in his writings that if science found a way to “cure” aging, people could live 150 years. “In mundane circles,” reported the Paris correspondent of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, later renamed the New England Journal of Medicine, Metchnikoff’s theories “have had a succès fou, and as they fitted in exactly with their wishes, which were to remain young and beautiful on the female side, and vigorous on the male, everybody in this town has since then been taking Metchnikoff’s milk with a fervor proportionate to the scientific authority of its promoter.”

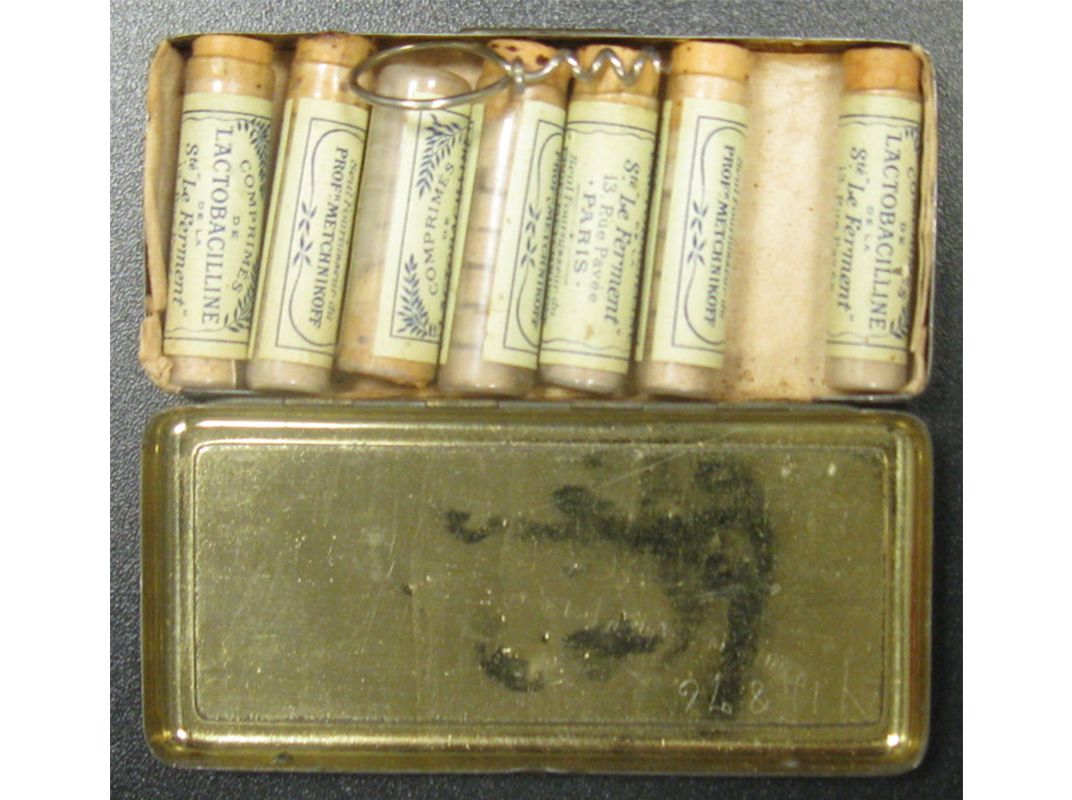

By then, milk-souring bacteria had sprouted into an international business. Drugstores throughout Europe and the United States were offering yogurt itself or Bulgarian cultures in the form of tablets, powders and bouillons—precursors of today’s probiotics. These were to be consumed as is or used to make sour milk at home in jars or in special, new incubators marketed under such brand names as Sauerin, Lactobator or Lactogenerator.

Inevitably, the yogurt craze became embedded in popular culture. Perhaps the epitome was the pantomime Jack and the Beanstalk, a spoof on the fairy tale, presented by a London theater in December, 1910. According to a rave review in the Times of London, it featured a king who was prescribed the “sour-milk cure” for his gout, as well as “a Metchnikoff cow” that gave sour milk.

When Metchnikoff died in 1916, though, at the not-so-old age of 71, yogurt’s image as a fountain of youth was permanently tarnished.

In 1919, a small business called Danone (later Dannon in the United States) latched onto yogurt’s less glamorous reputation for helping digestion and started selling sour milk in clay pots through pharmacies as a remedy for children with intestinal problems. In the United States, yogurt continued to be regarded largely as an ethnic or fad food for decades. But U.S. sales started to rise in the 1960s, when counter-culture folks adopted yogurt as one of their back-to-basics foods, and dieters started embracing the new, low-fat yogurts. And sales have been growing ever since.

Most contemporary scientists ridiculed the connection Metchnikoff made between aging and intestinal microbes; for almost a hundred years, no one picked up the topic. But in the past few years, a number of scientific studies have revealed that the intestinal flora—or the microbiome, as it is now known—does affect lifespan in worms and flies. It is as yet unknown whether this effect applies to mammals, including humans, but the impact of the microbiome on aging has suddenly turned into a topic of serious research. So Metchnikoff’s ideas about aging weren’t crazy after all, only a century ahead of their time.

Adapted from Immunity: How Elie Metchnikoff Changed the Course of Modern Medicine by Luba Vikhanski.