This Scientist Seeks Out the Secret History of Other Worlds

Maria Zuber has spent her career enabling discoveries beyond Earth. She says the best is yet to come

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/45/e245c091-72de-4176-9cc7-ef08e3856b3d/zuber-560.jpg)

Many a man, woman and child have stared out into the glittering night, pondering what truths lie yet undiscovered in the vastness of the firmament. Mostly, though, that ends when the outdoors gets too cold or insect-infested, and men, women and children abandon stargazing for the comforts of home.

But neither temperature nor mosquitoes have ever dampened for Maria Zuber curiosity. It’s a pursuit impossible for her to ignore even if she wanted to, an urge she only half-jokingly attributes to a "genetic predilection" to explore space.

At 58 years old, that drive has led Zuber to accumulate a staggering roster of professional responsibilities and accomplishments, many of them never before achieved by a woman. Count them: first woman to run a NASA planetary spacecraft mission; first woman to lead a science department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; and one of the first two women to receive NASA’s Distinguished Public Service Medal for her contributions to science (in 2004, along with Neil deGrasse Tyson).* She still runs an active research lab at MIT—and somehow squeezes out time each week to review submissions for the journal Science.

“Colleagues who follow her exploits would be left gasping for breath, wondering when she’d meet her limits,” laughs Sean Solomon, director of the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University, who has known and worked with Zuber since she was a geophysics graduate student at Brown University. Despite taking on ever more ambitious, complicated projects, Solomon says Zuber is the embodiment of grace under pressure.

Zuber demurs, and says that’s all beside the point. “You don’t know that something is doable unless you give it a try,” she says. “I think if I had one quality to attribute it to, it’s that I haven’t been afraid to fail. I just think the worst thing would be to not have tried and then always wonder what might have been.”

With her recent appointment to the board of the National Science Foundation and still fulfilling her duties as MIT’s vice president for research, Solomon wonders whether Zuber may finally be reaching the maximum trajectory of what she can do all at once. Then he checks himself: “But, none of us are entirely sure she can’t take on more.”

All of this because Zuber was compelled to follow her passion for looking at the sky and the earth.

As a child, Zuber spent many nights in the fields around rural Summit Hill, Pennsylvania with her coal-miner grandfather, peering at the heavens through a telescope he scrimped out of his wages to be able to buy. Her mother, a housewife and part-time reading aide, and father, a police officer, would sometimes shake their heads at her “obsession,” which included building her own telescopes by the age of 7 years old.

So it was only natural that she would go to on to pursue astronomy—and an extra geology degree knocked out during her senior year—at the University of Pennsylvania, followed by graduate and doctoral work at Brown.

She arrived at planetary science—specifically, the geology and physics of worlds other than Earth—thanks to a series of events that could almost be called serendipitous. But that’s not quite fair to Zuber, who seems to be exceptionally tuned into gaps in science unlocked by recent advances.

To wit: While still in college, in a bar, she watched crisply detailed images of Jupiter broadcast home by Voyager as it plunged deeper into the outer solar system, and found herself enticed by the possibilities of an emerging field of study.

“We were looking at things we’d never seen before. Discoveries were assured,” she says. “A lot of science tends to look at a very well-focused problem, but in planetary science, you can ask really big-picture questions. I feel so fortunate that I was born at the right time to be able to make really fundamental contributions to science.”

Part of that contribution has been in creating the gear needed to make new measurements and observations. Throughout her career, if the tools she needed didn’t exist, she’s helped produce them; if adequate data for her planetary models weren’t there, she’s worked to go and fetch it.

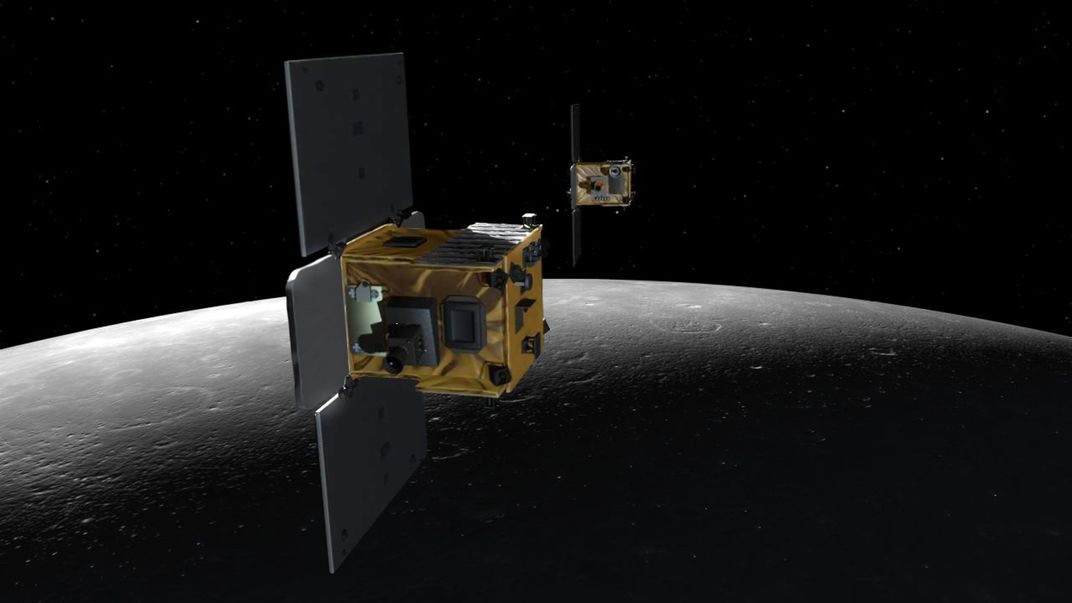

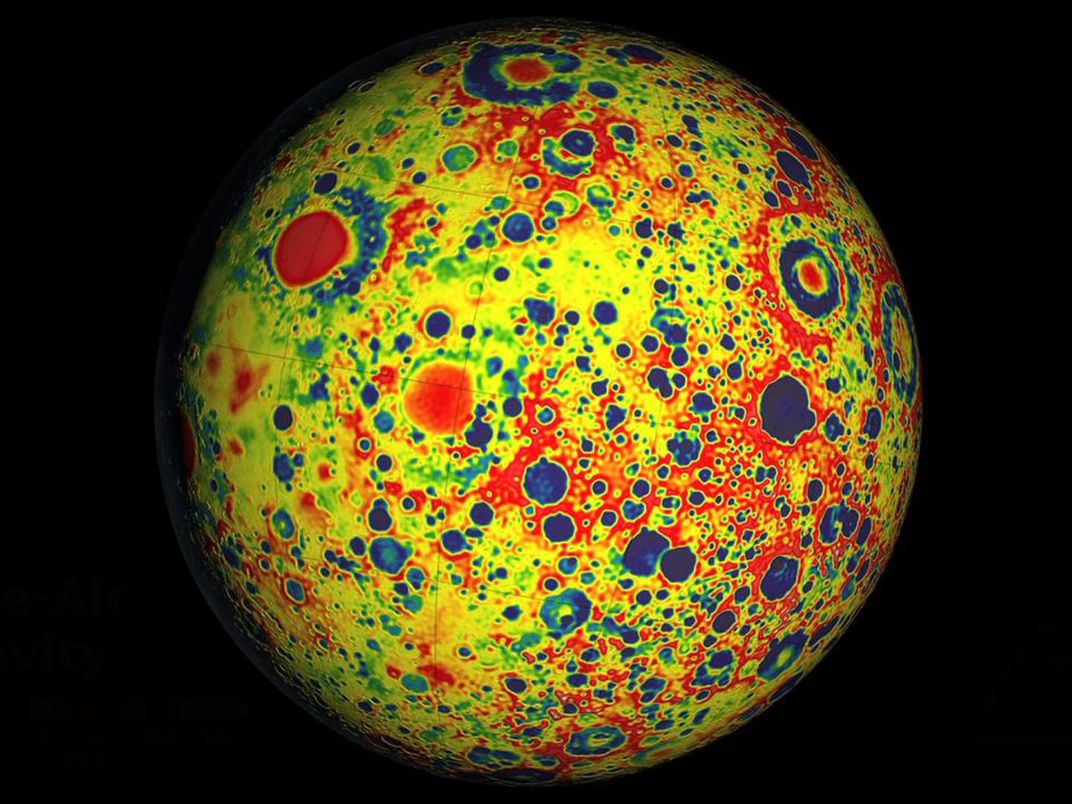

Zuber is best known for her work on NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory mission, or GRAIL, the operation she led in 2011 and 2012 to send a pair of low-flying probes to chart the gravity field of the moon. Dubbed Ebb and Flow, lasers onboard the twin spacecraft measured variances—to within a tenth of a micron—in altitude and distance as they flew over the mountains, craters, plains and subterranean features of the moon. The result: a high-resolution map of the moon’s gravitational field.

But she came to lasers only because a radar mapping instrument mission she’d been working on as a postdoc at Goddard Space Flight Center was scrapped after the Challenger shuttle disaster, as she described in a recounting of her career arc for an MIT oral history project in 2011.

Looking for a possible replacement, it occurred to her that the billions of dollars the Reagan administration was putting into research for its “Star Wars” laser defense initiatives must have something useful to glean. So she got her security clearance, familiarized herself with current laser technology, then worked to water it down to civilian status. Included as part of a cheaper, more efficient mapping mission proposal, it blew all the other, radar-based, planetary mapping proposals out of the water.

“She’s easy to work with, but very hard to compete against,” Solomon says. “Maria sets very high goals. If anyone is working in a similar area, or proposing a competing mission or experiment, all of her competitive juices come into play. She really, really wants to do the best.”

Zuber has been studying planets with the help of lasers ever since.

Though GRAIL was arguably a high point in her career, she has also been an active participant in other missions to the moon as well as to Mercury, Mars, and the asteroids Ceres, Vesta and Eros.

Some of the best contributions to planetary science can come as a byproduct of the intended investigation, she says. GRAIL’s primary mission, for example, was to investigate the structure and organization of the lunar interior, from crust to core.

But as the data started returning and Zuber and her team were able begin analyzing how the moon is built from the inside out, they were able to piece together some previously unknown facets of the lunar architecture.

“Most of the focus has been on the surface, because that’s most accessible,” Zuber says. “The moon is our closest relative, and like with people, it’s not what’s on the outside of a person that makes you special but what’s inside. By not understanding the interior structure of the moon, we had a terribly misunderstood member of the family. We don’t want the solar system to be a dysfunctional family.”

Though it was well-known that the moon’s many craters, pits and pockmarks were created through eons of collisions with errant space debris, what wasn’t known was the extent of the annihilation of the crust caused by those impacts. Rather than mere surface scars, the destruction of the surface extended deep within the moon’s crust—evidence preserved from the solar system’s earliest days.

“The lunar crust wasn’t just broken in places, it was absolutely pulverized,” Zuber says.

Earth, too, would have been getting banged up around the same time, when the first life was possibly forming in the planet’s young oceans. “Goodness knows how many times life tried to get started and something came in and whacked it. It’s a much, much more extreme environment than we even thought,” she says.

The extent to which the lunar crust was broken up also gives insights into how any nascent life on Mars may have fared—with evidence that water does exist on the red planet, the breakup of the upper crust may have allowed a great deal of water to sink tens of kilometers below the surface, potentially taking any life along with it.

“If life developed—and that’s a huge if—but if it did, drilling beneath the surface will be a good place to look,” Zuber says. “There’s such a low probability of finding it, but the stakes are so high that you’ve got to look.”

The intrigue of finding possible life on Mars notwithstanding, the real value of understanding how the inner planets got demolished during the early epochs of the solar system ultimately helps scientists understand the behavior of our own planet in ways that aren’t obvious from a terrestrial vantage point. The study of multiple systems that share a common origin, at least, provides more data to compare for study of plate tectonics on Earth.

Despite great strides in the study of the movement of Earth’s great continental plates, it’s still not enough to predict earthquakes or other volcanic activity to any real degree. “The realization of how complex the Earth is a long-standing question. And it isn’t like scientists haven’t been trying,” Zuber says.

The GRAIL project has its final team meeting in August in Woods Hole, Mass., signaling the official end of the mission. But as Zuber assumes her duties heading up the National Science Board, she expresses nothing but appreciation for the support her family and colleagues have provided to enable her ascent.

“I don’t deserve credit for doing anything on my own,” Zuber insists. “Everything I’ve accomplished has been based on working with really talented colleagues and students.”

That doesn’t mean the end of her efforts to contribute to the exploration of space. Far from it, as she’s involved in putting together another mission proposal for NASA, which is looking to map the surface and interior of a metallic asteroid or the remnant of a planetary core. She’s also hopeful that her role on the National Science Board will help enable others like her to make their own great strides—men and women alike.

“There are still lots of incredible discoveries to be made,” Zuber says. “I would like to see as many things going to space and measuring something as possible, because I can’t stand not knowing what’s up there.”

Editor's note, August 16, 2016: An earlier version of this story misstated that Zuber was the first female chair of the National Science Board.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)