Scientists Use Cadaver Hands to Study the Dangers of Pumpkin Carving

A rigorous experiment compared pumpkin-carving tools to determine the safest way to carve a pumpkin

![]()

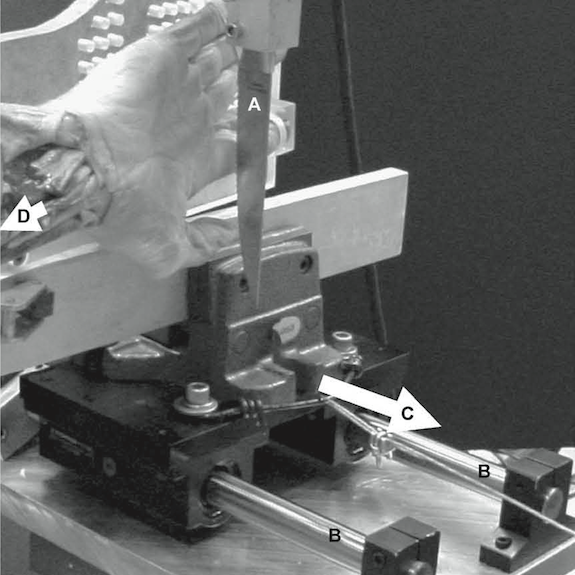

Yes, that’s a dead human hand in this experimental setup to test the safety of various pumpkin-cutting tools. Image via Preventive Medicine

What was a group of orthopedic physicians doing with a hydraulic press, a set of kitchen knives, a set of pumpkin carving tools and a dead human hand? Well, if the headline didn’t give it away, then the approaching holiday might give you a hint about their exceedingly creepy experimental setup.

In 2004, a team from SUNY Upstate Medical University in Syracuse decided to rigorously investigate the potential risks of pumpkin carving, comparing the threats posed by conventional kitchen knives with those of other tools specifically intended for pumpkins. As Marc Abrahams (the editor of the Annals of Improbable Research) recently pointed out at the Guardian, the research published in the journal Preventive Medicine provides the most comprehensive account of pumpkin-carving danger we have to date.

Pumpkin carving, it turns out, can be a rather dangerous pursuit. Image via Flickr user Saeru

“Even with optimal treatment, injuries from pumpkin carving accidents may leave people with compromised hand function,” they wrote. Common pumpkin-carving injuries come in a number of forms: hand punctures, resulting from instances where a knife is accidentally pushed through the pumpkin and contacts the opposite hand stabilizing it; and lacerations, caused by the cutting hand slipping off the knife handle and sliding across the blade.

Because of these risks, many companies market pumpkin-specific carving tools, claiming that they’re safer than sharp knives. Naturally, the researchers wanted to test these supposed safety benefits. As they noted, “evidence that they are safer is required before these knives can be recommended.”

In order to find such evidence, they compared various carving instruments—a serrated kitchen knife, a plain knife and two brands of pumpkin-specific tools (the Pumpkin Kutter and the Pumpkin Masters’ Medium Saw)—by placing each one in the grip of a hydraulic press and carefully measuring exactly how much force needed to be applied to pierce into a pumpkin and to lacerate a human hand. Since live volunteers for such an experiment might not be all that plentiful, they used six cadaver hands, harvested at the elbow.

The four knives tested: a Pumpkin Masters’ medium saw, a Pumpkin Kutter, a serrated knife and a plain knife. Image via Preventive Medicine

In the first stage of the study, when the implements were tested on a pumpkin, each one was pushed into the squash’s flesh at the rate of 3 mm per second. The pumpkin-specific instruments performed as advertised, cutting into the pumpkins more easily than the kitchen knives. Theoretically, if less force is needed to actually carve the pumpkin, the risk of pushing too hard and accidentally cutting yourself should be lower.

In the second phase, each of the cutting tools was tested on the cadaver hands in two different ways: the researchers measured how much force was needed to lacerate the finger and to puncture the palm. In this case, the kitchen knives cut more easily into the hands, requiring less force and causing “more skin lacerations that would require suturing than either pumpkin knife.” When it comes to hands, the knives were more dangerous.

The researchers’ conclusions? “Tools designed specifically for pumpkin carving may indeed be safer. Use of these products, and increased overall awareness of the risks of pumpkin carving in general, which clinicians could help promote, might reduce the frequency and severity of pumpkin carving injuries.”

Another pressing question solved by science. No word yet on what happened to the lacerated and punctured cadaver hands afterward.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)