Scott Kelly’s Journey Home After His Year in Space

America’s longest-orbiting astronaut describes his rocky return to Earth in this adaptation from his book ‘Endurance’

:focal(1201x531:1202x532)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e7/42/e742ebff-2a0c-4840-ac4c-299a821de40a/scott-kelly.jpg)

Today is my last in space. It’s March 1, 2016, and I’ve been up here for 340 days, along with my colleague and friend Mikhail “Misha” Kornienko. In my time onboard the International Space Station during this mission—this is my second time here—I’ve seen 13 crew mates come and go. I’ve done three grueling, exhilarating spacewalks—two planned, plus an emergency trip outside to move a stuck piece of machinery on the station’s exterior that would have prevented a Russian Progress spacecraft, due in a week, from docking. At one point, I spent several days frantically trying to fix a dangerously malfunctioning carbon dioxide scrubber. I even had the opportunity to put on a gorilla suit, sent up to me by my brother, Mark, to scare my crew mates and the NASA folks on the video feed.

But, most important, I’ve spent a significant amount of time on science. Our mission for NASA and the Russian space agency Roscosmos to spend a year in space is unprecedented. A normal mission to the space station lasts four to six months, so scientists have a good deal of data about what happens to the human body in space for that length of time. But little is known about what happens after Month 6.

To find out, Misha and I have gathered all kinds of data for studies on ourselves. I’ve taken blood samples for analysis back on Earth, and kept a log of everything from what I eat to my moods. I’ve taken ultrasounds of my blood vessels, my heart, my eyes and my muscles. Because my brother, Mark, and I are identical twins, I am also taking part in an extensive study comparing the two of us throughout the year, down to the genetic level. The space station is an orbiting laboratory, and I’ve also spent a lot of time working on other experiments, from fluid dynamics to combustion efficiency.

I’m a firm believer in the importance of the science being done here. But it’s just as important that the station is serving as a foothold for our species in space. From here, we can learn more about how to push out farther into the cosmos—for example, to Mars.

And I have just one more task to complete our mission: getting home.

**********

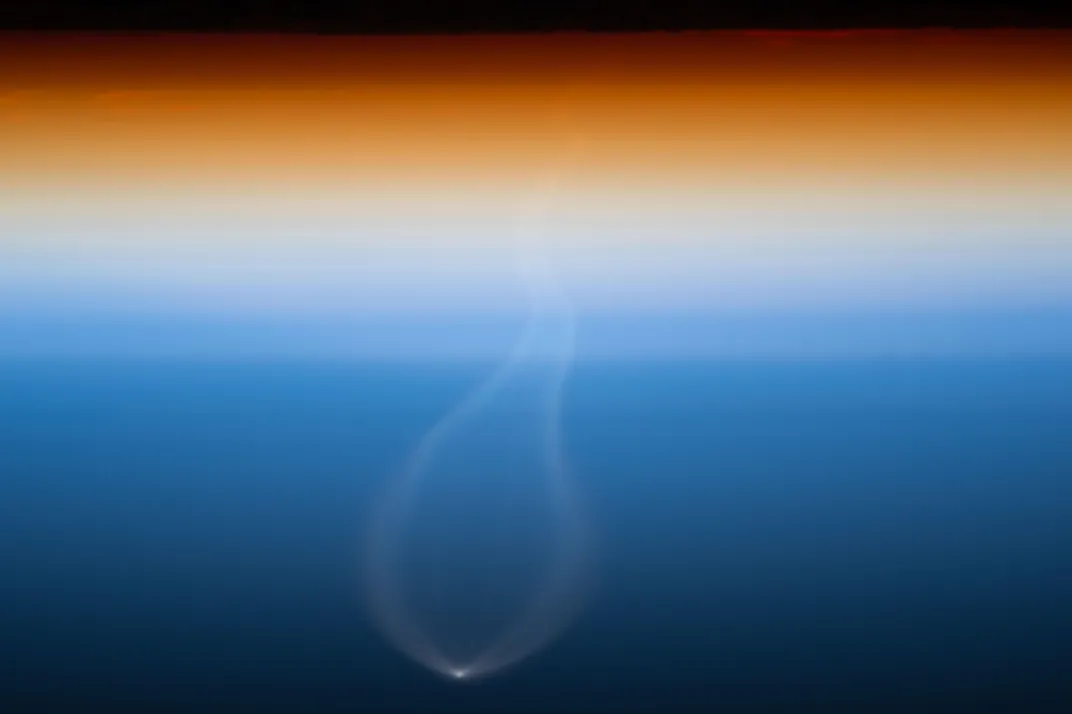

Returning to Earth in a Russian Soyuz capsule is one of the most dangerous moments of the past year. Earth’s atmosphere is naturally resistant to objects entering from space. Most simply burn up from the heat caused by the tremendous friction. This generally works to everyone’s advantage, as it protects the planet from the meteorites and orbital debris that would otherwise rain down. And we exploit this property when, on the station, we fill a visiting vehicle with trash and set it loose to burn up in the atmosphere. But the atmosphere’s density is also what makes a return from space so difficult. My two Russian crew mates and I must survive a fall through the atmosphere that will create temperatures up to 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit in the form of a fireball just inches from our heads, and deceleration forces up to four times the strength of gravity.

Endurance: My Year in Space, A Lifetime of Discovery

A stunning memoir from the astronaut who spent a record-breaking year aboard the International Space Station--a candid account of his remarkable voyage, of the journeys off the planet that preceded it, and of his colorful formative years.

The trip to Earth will take about three and a half hours. After pushing away from the station, we will fire the braking engine to slow us slightly and ease our way into the upper layers of the atmosphere at just the right speed and angle. If our approach is too steep, we could fall too fast and be killed by excessive heat or deceleration. If it’s too shallow, we could skip off the atmosphere’s surface like a rock thrown at a still lake, only to enter much more steeply, likely with catastrophic consequences.

Assuming our “deorbit burn” goes as planned, the atmosphere will do most of the work of slowing us down, while the heat shield will (we hope) keep the temperatures from killing us. The parachute will (we hope) slow our descent once we are within ten kilometers of the Earth’s surface, and the soft landing rockets will (we hope) fire in the seconds before we hit the ground to further slow our descent. Many things need to happen perfectly, or we will be dead.

My crew mate Sergey Volkov has already spent days stowing the cargo we will be bringing with us on the Soyuz—small packages of personal items, water samples from the station’s water recycling system, blood and saliva for the human studies. Most of the storage space in the capsule is devoted to things we hope we never have to use: survival equipment, including a radio, compass, machete, and cold weather gear in case we land off course and must wait for rescue forces.

Because our cardiovascular systems have not had to oppose gravity for all this time, they have become weakened and we will suffer from symptoms of low blood pressure on our return to Earth. One of the things we do to counteract this is fluid-loading—ingesting water and salt to try to increase our plasma volume before we return. NASA gives me a range of options that include chicken broth, a combination of salt tablets and water, and Astro-Ade, a rehydration drink developed for astronauts. The Russians prefer more salt and less liquid, in part because they would rather not use the diaper during re-entry. Having figured out what worked for me on three previous flights, I stick to drinking lots of water and wearing the diaper.

I struggle into my Sokol spacesuit and try to remember the day I put this same suit on for launch, a day when I’d eaten fresh food for breakfast, had taken a shower, and had gotten to see my family.

Now that it’s time to go, we float into the Soyuz, and then squeeze ourselves inside the descent capsule, one by one. We sit with our knees pressed to our chests, in seat liners custom-molded to fit our bodies. We will go from 17,500 miles per hour to a hard zero in less than 30 minutes, and the seats must work as designed to keep us on the winning side. We strap ourselves into the five-point restraints as best we can—easier said than done when the straps are floating around and any tiny force pushes us away from the seats.

A command from mission control in Moscow opens the hooks that hold the Soyuz to the ISS, and then spring-force plungers nudge us away from the station. Both of these processes are so gentle that we don’t feel or hear them. We are now moving a couple of inches per second relative to the station, though still in orbit with it. Once we are a safe distance away, we use the Soyuz thrusters to push us farther from the ISS.

Now there is more waiting. We don’t talk much. This position creates excruciating pain in my knees, as it always has, and it’s warm in here. A cooling fan circulates air within our suits, a low comforting whir, but it’s not enough. I find it hard to stay awake. I don’t know if I’m tired just from today or from the whole year. Sometimes you don’t feel how exhausting an experience has been until it’s over and you allow yourself to stop ignoring it. I look over at Sergey and Misha, and their eyes are closed. I close mine too. The sun rises; about an hour later, the sun sets.

When we get word from the ground that it’s time for the deorbit burn, we are instantly, completely, awake. It’s important to get this part right. Sergey and Misha execute the burn perfectly, a four-and-a-half-minute firing of the braking engine, which will slow the Soyuz by about 300 miles per hour. We are now in a 25-minute free fall before we will slam into Earth’s atmosphere.

When it’s time to separate the crew module—the tiny, cone-shaped capsule we are sitting in—from the rest of the Soyuz, we hold our breath. The three modules are exploded apart. Pieces of the habitation module and instrumentation compartment fly by the windows, some of them striking the sides of our spacecraft. None of us mentions it, but we all know that it was at this point in a Soyuz descent in 1971 that three cosmonauts lost their lives, when a valve between the crew module and the orbital module opened during separation, depressurizing the cabin and asphyxiating the crew. Misha, Sergey and I wear pressure suits that would protect us in the case of a similar accident, but this moment in the descent sequence is still one we are glad to put behind us.

We feel gravity begin to return, first slowly, then with a vengeance. Soon everything is strangely heavy, too heavy—our tethered checklists, our arms, our heads. My watch feels heavy on my wrist, and breathing gets harder as the G forces clamp down on my trachea. I extend my head up as I struggle to breathe. We are falling at 1,000 feet per second.

We hear the wind noise building as the thick air of the atmosphere rushes past the module, a sign that the parachute will soon be deployed. This is the only part of re-entry that is completely automated, and we concentrate on the monitor, waiting for the indicator light to show that it worked. Everything depends on that parachute, which was manufactured in an aging facility outside Moscow using quality standards inherited from the Soviet space program.

The chute catches us with a jerk, rolling and buffeting our capsule crazily through the sky. I’ve described the sensation as going over Niagara Falls in a barrel that is on fire. In the wrong frame of mind this would be terrifying, and from what I’ve heard, some people who have experienced it have been terrified. But I love it. As soon as you realize you’re not going to die, it’s the most fun you’ll ever have in your life.

Misha’s checklist comes loose from its tether and flies at my head. I reach up and grab it out of the air with my left hand. The three of us look at each other with amazement. “Left-handed Super Bowl catch!” I shout, then realize Sergey and Misha might not know what the Super Bowl is.

After all the tumult of the re-entry, the minutes we spend drifting at the whim of the parachutes are oddly calm. Sunlight streams in the window at my elbow as we watch the ground get closer and closer.

From their position in helicopters nearby, rescue forces count down over the communications system the distance to go until landing. “Open your mouth,” a voice reminds us in Russian. If we don’t keep our tongues away from our teeth, we could bite them off on impact. When we are only one meter from the ground, the rockets fire for the “soft” landing (this is what it’s called, but I know from experience that the landing is anything but soft).

I feel the hard crack of hitting Earth in my spine and my head bounces and slams into the seat, the sensation of a car accident.

We are down in Kazakhstan. We have landed with the hatch pointing straight up rather than on one side, and will wait a few minutes longer than usual while the rescue crew brings a ladder to extract us from the burned capsule.

When the hatch opens, the Soyuz fills with the rich smell of air and the bracing cold of winter.

I’m surprised to find that I can unstrap myself and pull myself out of my seat despite the fact that gravity feels like a crushing force. With the help of the rescue crew, I pull myself out of the capsule to sit on the edge of the hatch and take in the landscape all around. The sight of so many people—maybe a couple hundred—is startling. It’s been a year since I’ve seen more than a handful of people at a time.

I pump my fist in the air. I breathe, and the air is rich with a fantastic sweet smell, a combination of charred metal and honeysuckle. My flight surgeon Steve Gilmore is there, as is NASA’s chief astronaut Chris Cassidy and the deputy ISS program manager, plus some cosmonauts and many members of the Russian rescue forces. The Russian space agency insists on having the rescue crew help us down from the capsule and deposit us into nearby camp chairs for examination by doctors and nurses. We follow the Russians’ rules when we travel with them, but I wish they would let me walk away from the landing. I feel sure I could.

Chris hands me a satellite phone. I dial the number for Amiko Kauderer, my longtime girlfriend—I know she’ll be at mission control in Houston along with my daughter Samantha, my brother and close friends, all watching a live feed on the huge screens. (My younger daughter Charlotte is watching from home in Virginia Beach.)

“How was it?” Amiko asks.

“It was f---king medieval,” I say. “But effective.”

I tell her I feel fine. If I were on the first crew to reach the surface of Mars, just now touching down on the red planet after a yearlong journey and a wild hot descent through its atmosphere, I feel that I would be able to do what needed to be done. I wouldn’t want to have to build a habitation or hike ten miles—for a little while, I’m walking around like Jar Jar Binks—but I know I could take care of myself and others in an emergency, and that feels like a triumph.

I tell Amiko I’ll see her soon, and for the first time in a year that’s true.

**********

I’m sitting at the head of my dining room table at home in Houston, finishing dinner with my family: Amiko and her son, Corbin; my daughters; Mark and his wife, Gabby Giffords; Mark’s daughter Claudia; and our father, Richie. It’s a simple thing, sitting at a table and eating a meal with those you love, and many people do it every day without giving it much thought. For me, it’s something I’ve been dreaming of for nearly a year. Now that I’m finally here, it doesn’t seem entirely real. The faces of the people I love, the chatter of many people talking together, the clink of silverware, the swish of wine in a glass—these are all unfamiliar. Even the sensation of gravity holding me in my chair feels strange, and every time I put a glass down on the table there’s a part of my mind that is looking for a dot of Velcro or a strip of duct tape to hold it in place. I’ve been back on Earth for 48 hours.

I push back from the table and struggle to stand up, feeling like an old man getting out of a recliner.

“Stick a fork in me,” I announce. “I’m done.” Everyone laughs. I start the journey to my bedroom: about 20 steps from the chair to the bed. On the third step, the floor seems to lurch under me, and I stumble into a planter. Of course it wasn’t the floor—it was my vestibular system trying to readjust to Earth’s gravity. I’m learning to walk again.

“That’s the first time I’ve seen you stumble,” Mark says. “You’re doing pretty good.” An astronaut himself, he knows from experience what it’s like to come back to gravity after being in space.

I make it to my bedroom without further incident and close the door behind me. Every part of my body hurts. All of my joints and all of my muscles are protesting the overwhelming pressure of gravity. I’m also nauseated, though I haven’t thrown up. I strip off my clothes and get into bed, relishing the feeling of sheets, the light pressure of the blanket over me, the fluff of the pillow under my head. I drift off to sleep to the comforting sound of my family talking and laughing.

A crack of light wakes me: Is it morning? No. It’s just Amiko coming to bed. I’ve only been asleep for a couple of hours. But I feel delirious. It’s a struggle to come to consciousness enough to move, to tell Amiko how awful I feel. I’m seriously nauseated now, feverish, and my pain is more intense.

“Amiko,” I finally manage to say.

She is alarmed by the sound of my voice.

“What is it?” Her hand is on my arm, then on my forehead. Her skin feels chilled, but it’s just that I’m so hot.

“I don’t feel good,” I say.

I struggle to get out of bed, a multi-stage process. Find the edge of the bed. Feet down. Sit up. Stand. At every stage I feel like I’m fighting through quicksand. When I’m finally vertical, the pain in my legs is awful, and on top of that pain I feel something even more alarming: All the blood in my body is rushing to my legs. I can feel the tissue in my legs swelling. I shuffle my way to the bathroom, moving my weight from one foot to the other with deliberate effort. I make it to the bathroom, flip on the light, and look down at my legs. They are swollen and alien stumps, not legs at all.

“Oh, shit,” I say. “Amiko, come look at this.”

She kneels down and squeezes one ankle, and it squishes like a water balloon. She looks up at me with worried eyes. “I can’t even feel your ankle bones,” she says.

“My skin is burning, too,” I tell her. Amiko frantically examines me all over. I have a strange rash all over my back, the backs of my legs, the back of my head and neck—everywhere I was in contact with the bed. I can feel her cool hands moving over my inflamed skin. “It looks like an allergic rash,” she says. “Like hives.”

I use the bathroom and shuffle back to bed, wondering what I should do. Normally if I woke up feeling like this, I would go to the emergency room, but no one at the hospital will have seen symptoms of having lived in space for a year. NASA had suggested I spend my first few nights back at the Johnson Space Center, but I declined, knowing I would be in regular touch with my flight surgeon. I crawl back into bed, trying to find a way to lie down without touching my rash. I can hear Amiko rummaging in the medicine cabinet. She comes back with two ibuprofen and a glass of water. As she settles down, I can tell from her every movement, every breath, that she is worried about me.

The next few weeks are an endless series of medical tests—CAT scans, ultrasounds, blood draws. One test, to measure how much muscle mass I lost in space, involves zapping my leg muscles with electricity. This is quite unpleasant. I notice an obvious deficit when it comes to my hand-eye coordination, and my balance. But I also notice that my performance starts to improve pretty quickly. During my first three weeks home, I have one day off from the tests.

After a week, the nausea starts to subside. After two weeks, my leg swelling goes away, about the same time as the rashes. Those were caused by the fact that my skin wasn’t really subjected to pressure for a whole year, so that even just sitting or lying down created a reaction. The most frustrating lingering effect is the soreness in my muscles, joints and feet. It is incredibly painful, and it takes several months before it really goes away.

The most surprising thing is how hard I find it to readapt to routine things. After a year in the incredibly controlled and constraining environment of the space station, I find the choices you have to make constantly on Earth, about what you’re going to do, or not do, are almost overwhelming. I imagine it’s almost like people released after a long time in prison. It takes a while to get used to that again.

**********

Science is a slow-moving process, and it may be years before any great understanding or breakthrough is reached from the studies of my time in space and my return to Earth. Early results have scientists excited about what they’re seeing, from differences in gene expression between my brother and me to changes in our gut microbiomes and the lengths of our chromosomes, and NASA plans to release a summary of findings next year. Sometimes the questions science asks are answered by other questions, and I’ll keep having tests done once a year for the rest of my life. This doesn’t particularly bother me. It’s worth it to contribute to advancing human knowledge.

I remember my last day on the space station, floating toward the Russian segment to board the Soyuz, and consciously turning around and looking back. I knew with absolute certainly that I would never see that place again. And I remember the last time I looked out the window, and thinking to myself, This is the last view of Earth I’m going to have.

People often ask me why I volunteered for this mission, knowing the risks I would be exposed to every moment I lived in a metal container orbiting Earth at 17,500 miles per hour. I don’t have a simple answer, but I know that the station is a remarkable achievement, not only of technology but also of international cooperation. It has been inhabited nonstop since November 2, 2000, and more than 200 people from 18 nations have visited the place in that time. I’ve spent more than 500 days of my life there.

I also know that we won’t be able to push out farther into space, to a destination like Mars, until we can learn more about how to strengthen the weakest links in the chain—the human body and mind. During my mission, I testified from the ISS during a meeting of the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology. One representative pointed out that the planets will be lined up advantageously for a flight to Mars in 2033. “Do you guys think that’s feasible?” he asked.

I told him that I do, and that the most difficult part of getting to Mars is the money. “I think it’s a trip that is worth the investment,” I said. “There are things tangible and intangible we get from investing in spaceflight, and I think Mars is a great goal for us. And I definitely think it’s achievable.”

If I’d had the opportunity, in fact, I would have signed up myself.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.