I arrived on Kangaroo Island bracing myself for the sight of acres of blackened trees and white ash, but I had not expected the parasitic bright green vines wrapped around almost every charred trunk, glowing phosphorescent in the sunlight. This was no parasite, I learned. It was epicormic growth, bursting directly from the burnt trunks themselves, a desperate bid for photosynthesis in the absence of a leaf canopy.

The growth looks nothing like a eucalyptus tree’s normal adult leaves. It’s soft and waxy, with rounded edges instead of long pointy tips, and it blooms from cracks in the trunks or right from the tree’s base, rather than along the branches where leaves typically grow. It is beautiful, and also very strange, in keeping with the surreal phenomena that became almost commonplace over this past apocalyptic Australian summer, even before the coronavirus pandemic further upended life as we know it. A few weeks earlier, in Sydney, I’d watched red-brown rain fall to the ground after rain clouds collided with ash in a smoke-filled sky. During a recent downpour here on Kangaroo Island, burnt blue gum trees foamed mysteriously, as if soap suds had been sprayed over them.

Even in less strange times, Kangaroo Island can feel like the edge of the earth. Although it sits fewer than ten miles off the southern coast of Australia, about 75 miles from Adelaide, it is a geographical Noah’s Ark; its isolation from the mainland 10,000 years ago because of rising seas transformed it into an ecological haven. It is vast and rugged, with dramatic views of bush or sea- or cliff-scapes in every direction. National parks or protected wilderness areas make up a third of the island’s 1,700 square miles. Much of the rest of the island is farmland or privately owned backcountry. In recent years, the island has rebranded itself as a high-end tourist paradise, with unspoiled wilderness, farm-to-table produce, fresh oysters, and wine from local vineyards. But while there are luxury accommodations here and there, the island’s few small settlements feel decidedly unglamorous, befitting laid-back country and coastal towns.

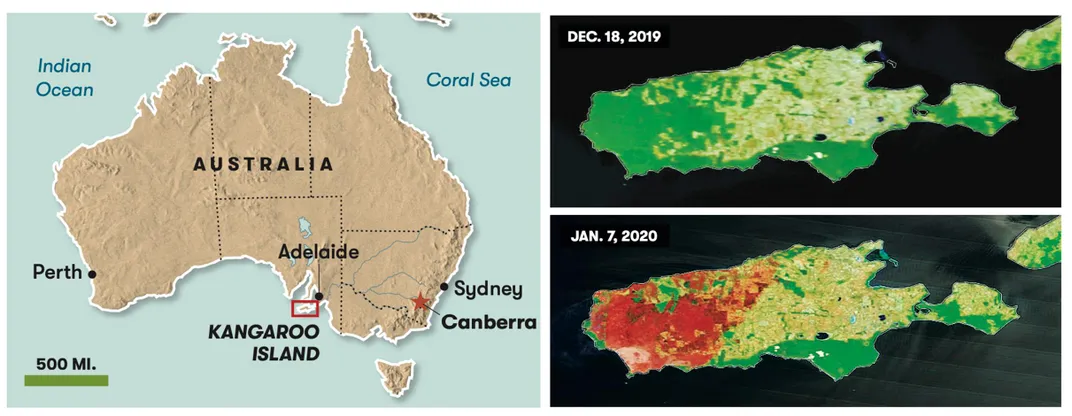

The fires started here in December, after dry lightning strikes on the island’s north coast and remote western bushland areas, and then escalated and jumped containment lines, ripping through the island in early January, with high winds and hot temperatures fueling the front. Two people died, and hundreds of properties were affected, many of them farms. Tens of thousands of stock animals were lost in the blaze. While the bushfires all over Australia were horrific, burning more than 16 million acres—nearly eight times the area lost to fire in Brazil’s Amazon basin in 2019—people around the world focused on Kangaroo Island because of the relative scale of the fires, which consumed close to half the island, as well as the concentrated death and suffering of the island’s abundant wildlife, including wallabies, kangaroos, possums and koalas. Wildlife experts worried that certain vulnerable species endemic to the island, such as the glossy black-cockatoo and a mouse-like marsupial known as the Kangaroo Island dunnart, might be lost forever.

Flinders Chase National Park, the vast nature preserve encompassing the island’s western edge, is closed indefinitely. There were rumors that parts of this natural bushland, which depends on fire to propagate, might never fully regenerate, because the heat from the fires was so intense that the soil seed bank may have been destroyed. Climate change researchers are warning that while fires in Australia are “natural,” they’re now so hot and frequent that even fire-adapted plants don’t have the chance to recover. A major fire burned 85 percent of Flinders Chase just 13 years ago. Matt White, an ecologist at the Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research, in Victoria, told me the fires are almost certainly decreasing biodiversity, despite “the oft-repeated rhetoric about the resilience of Australian flora.” Now the fires are out, and the immediate danger has passed, but life on the island is very far from normal. On certain parts of the northern coast, coves are silted with ash, black tide marks on the sand. Outside several towns are signs directing people to a Bushfire Last Resort Refuge, a chilling reminder of how bad things can get.

Kangaroo Island’s east coast, where I disembarked from the ferry, seemed relatively unscathed, but as I drove west through the central agricultural area, known as the Heartlands, I crossed a line into devastation. The color palette shifted from the beige and olive green of roadside scrub to charcoal trunks and scorched leaves in shades of orange, an uncanny simulacrum of autumn. The deeper into the fire grounds I went, the more the shock of that green epicormic growth scrambled my perceptions, as did the long green shoots of grass trees, emerging from their blackened, pineapple-shaped trunks. These trees are pyrophytic—they thrive after fires.

In Parndana, a small agricultural town, I saw a handwritten sign outside a makeshift store offering free groceries to families affected by the fires. A newsletter posted in a gas station reported on wineries going under, tourism businesses destroyed, and burned buildings requiring asbestos cleanup. In a roadside café near Vivonne Bay, on the south coast, I found mental health pamphlets and notices of counseling services and depression hot lines for a community reeling from losses. An Australian Psychological Society handout was stacked on the counter: “Now, a few months after the fires, many people are feeling tired and stressed, and they know that their daily struggle isn’t going to be over any time soon.”

The news media’s fixation on the island as the fires raged has created a complicated legacy for any reporter who turns up a month or two later. I was aware of being viewed with distrust by locals who’ve felt justifiably used in the media storm’s sudden descent and then abrupt disappearance. The press attention, combined with social media’s refraction of certain stories into trend roller coasters, has had the undeniable upside of an outpouring of genuine sympathy and generosity. An effort to recruit 120 volunteers to set up food and water stations for wildlife throughout devastated areas, organized by Australia’s Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, was inundated by more than 13,000 applications in a matter of days. Online crowdfunding has raised close to $2.5 million for Kangaroo Island bushfire recovery. But there’s a downside, too: a trading in the suffering of others. In the midst of the fires, one foreign journalist demanded of a shellshocked local resident, “I want to see burnt animals, and where those two people died.”

The immediate compassionate response of people pulling together in a crisis is now wearing thin. Tendrils of suspicion are snaking their way through the community, as locals assess the distribution of government and crowdfunded resources. Almost everybody has their heart in the right place, but the reality is that these decisions are political and contested. Old divides are widening—between, say, stock farmers in the Heartlands and those motivated to protect the island’s unique wildlife, to say nothing of the divide between locals and outsiders.

In every conversation, whether with a lodge manager, the owner of a feed business, or at the corner-store café, people wanted me to know that they’re upset about the way resources were being distributed. Special anger was reserved for rogue operators who have raised huge amounts of cash for wildlife work on the island, but with no real right to be there. Many singled out a Japanese outfit, reportedly run by a guy who turned up on the island with good intentions but zero clue. He had set himself up in a house in Kingscote, the island’s largest town (pop. around 1,800), and without coordinating with any recognized wildfire rescue operations was bringing in koalas from the wild that were healthy and didn’t need rescuing. Yet he had raised a small fortune through his organization’s website, from good people donating to the wrong cause. One islander told me, “I never realized disaster would be like this. At first, everyone helped. Then it got scary. It became about money, fame, randoms making an absolute killing.”

* * *

Kangaroo Island was given its modern name by the British navigator Matthew Flinders, who sailed the HMS Investigator to its shores in March 1802. The island was then uninhabited, but archaeologists later found stone tools and other evidence that ancestors of modern Aboriginal Tasmanians lived there thousands of years ago, at least until the island was cut off from the mainland, and possibly afterward. Rebe Taylor, a historian, writes that the Ngarrindjeri people of the coast opposite Kangaroo Island call it the “land of the dead,” and have a creation story about rising seas flooding a land bridge to the island.

Flinders and his men were amazed to find kangaroos—a subspecies of the mainland’s western greys—that were so unused to humans that they “suffered themselves to be shot in the eyes,” Flinders recalled in his expedition notes, “and in some cases to be knocked on the head with sticks.” In gratitude for this meat after four months without fresh provisions, he named it Kanguroo Island (misspelling his own). The French explorer Nicolas Baudin, sailing the Géographe, was disappointed not to have arrived before his English rival—their ships crossed paths as Flinders was leaving the island—but Baudin took 18 kangaroos with him, in the name of science. He made two of his men surrender their cabins to the animals in a bid to keep them alive. Baudin himself died from tuberculosis on the return journey, but some of the kangaroos survived, and they reportedly became part of the menagerie outside Paris owned by Napoleon’s wife, the Empress Josephine.

The recent fires killed as many as 40 percent of the island’s 60,000 or so kangaroos, yet worldwide attention has focused mostly on the fate of the koalas. At least 45,000 koalas, or some 75 percent or more of the island population, are thought to have died, and the crisis has revived an old controversy, with battle lines drawn anew between those who believe the koalas don’t deserve all the attention they’re getting and those who do.

Koalas have always had the species advantage of being considered cute, cuddly Australian icons, but they are not native to Kangaroo Island. They were introduced by wildlife officials only in the 1920s, from a breeding program on French Island, off mainland Victoria, with a founding population of fewer than 30 animals. The effort was an early attempt at conservation; habitat loss and hunters trading in their fur had driven koalas on the mainland to near extinction. Since then, the island had become overpopulated with koalas, which some people think are in danger of eating themselves out of house and home. In fact, since the late 1990s a government-run koala sterilization program has tried to stem population growth, not only for the koala population’s sake but also because the animals wreak destruction on native vegetation, including rough-bark manna gums, a type of eucalyptus that is key to preventing soil erosion, and paddock trees.

In addition, tens of thousands of koalas lived in eucalyptus plantations owned by a timber company with plans to harvest and export those trees; those animals would have to be moved eventually. Finally, the Kangaroo Island koalas are so highly inbred that some experts argue they may be of little use in bolstering northern Australia koala populations, which are classified as vulnerable.

Some wildlife advocates believe that preventing species extinction, or saving species that are endemic or unique to the island, should be the priority. They argue that funding would be better channeled toward specialists working to save the few remaining Kangaroo Island dunnarts, or Tammar wallabies (which are almost extinct in mainland South Australia), or pygmy possums, or endangered glossy black-cockatoos, which mainly feed on the seeds of casuarina trees (many of the trees burnt), or Ligurian bees, introduced in 1885 and believed to be the species’ last genetically pure population in the world.

Island farmers, meanwhile, feel that wildlife has unfairly consumed all the attention when so many stock animals burned during the fires. Many local farming families are descended from soldier-settlers who were given parcels of land after each of the world wars, which they worked hard to make productive in difficult circumstances. (The island’s natural soil quality is so poor, and the lack of surface water so severe, that most British colonists backed by the South Australian Company who settled the island in 1836 left after just five months.)

One islander confided to me that, while he felt bad for the farmers, stock animals are “replaceable,” and often covered by insurance, but wildlife is not; and while it may seem from news media coverage that Australia cares about its wildlife, the government in fact has an appalling track record when it comes to protecting wildlife and biodiversity. “Australia is a global deforestation hotspot,” Suzanne Milthorpe, from the Wilderness Society Australia, told me. “We are ranked second in the world for biodiversity loss, and three unique animals have gone extinct in the last decade alone. In comparison, the United States’ Endangered Species Act, which contains real protections against harm and habitat destruction, has been 99 percent successful at preventing extinction.” (Critics of American species conservation efforts point out that less than 3 percent of listed species have recovered sufficiently to be removed from protection.)

The koalas on Kangaroo Island were also fortunate in being able to be rescued at all; many were found sheltering high enough in the treetops to have escaped the flames. Hundreds were saved, treated and survived, and many were set free. Even young, orphaned koalas that must be bottle-fed and tended by hand would survive in captivity. By contrast, kangaroos and wallabies often couldn’t outrun the fires, and most of the rescued animals were badly burned and had little chance of recovery.

All of this helped me understand why legitimate, professional koala rescues on the island really do matter, and why the stakes feel so high for those who are skilled at and committed to this grueling work. For people desperate to help in the aftermath of the fires, rescuing and treating injured koalas and relocating koalas stranded in devastated forest areas has become a kind of humane religion, something to cling to and thus avoid descending into despair. Each and every rescue becomes a small but holy and tangible act to stem the wider suffering.

* * *

As soon as the story began to circulate, during the fires, that the Kangaroo Island Wildlife Park, outside Parndana, had become the impromptu center for the emergency treatment of burned wildlife, the place was inundated with journalists. The largely open-air park, which was already home to 600 or so animals, including snakes, wombats, cassowaries and an alligator, is owned by Dana and Sam Mitchell, a couple in their late 20s who moved to the island in 2013, after meeting while working at a wildlife park in Victoria. Journalists turned up even as the fires were burning, sleeping uninvited on the floor of the park’s café, barging into the Mitchells’ house at all hours.

This, to be fair, had some positive outcomes. An Australian TV channel, for instance, arranged for a popular home renovation show to build a wildlife hospital in the park, and the Mitchells have raised more than $1.6 million through crowdfunding to pay for professional veterinary costs, new buildings for wildlife care, and an islandwide koala rescue and rehabilitation program.

Yet it was overwhelming, too. Dana had to evacuate twice with their toddler, Connor, during the peak of the fires, while Sam stayed with staff and other family members to defend the property; the park and its animals were spared only after the wind changed direction as the fires were bearing down.

Meanwhile, hundreds of injured wild animals were brought to the park by Army personnel, the State Emergency Service and firefighters. As the roads reopened, many locals also began to arrive with injured wildlife, unsure where else to take them. Since the start of January, more than 600 koalas have been brought to the park, though not all have survived. Kangaroos with melted feet and koalas with melted paws had to be put out of their suffering. Orphaned baby koalas, called joeys, arrived with ears or noses burnt off. There were severely dehydrated older koalas with kidney disorders, and possums and wallabies blinded by the heat. “We were having to make it up on the spot,” Sam told me. “We were just a small wildlife park. These animals weren’t my responsibility, but nobody else was doing anything. The government wasn’t giving any direction.” In the first weeks, they operated a triage center out of a tin shed, with no power.

Sam and Dana soldiered on, and by now they have an impressive setup for koala rescue, treatment, rehabilitation and release. Behind their house is a series of brand-new buildings and dozens of koala enclosures, tended to by vets and veterinary nurses from Australia Zoo, Zoos South Australia, and Savem, a veterinary equivalent of Doctors Without Borders, as well as trusted local volunteers.

Sam has a grim sense of humor to help deal with the trauma of the past months, but he and Dana are physically and emotionally exhausted, as is everybody I met on the island. I felt bad asking them to retell their experiences during the fires, the ins and outs of how they survived, aware of the symbolic violence of being forced to perform your own private trauma for outsiders over and over again. Yet they did so, graciously, describing the unusual warning of white ash hitting the park even before the smoke. Desperate for sleep after staying awake several nights, Sam eventually brought a blanket outside and laid it on the grass, setting his phone alarm to go off every 15 minutes. He was worried that if he slept inside he wouldn’t see the fire coming.

In spite of their fatigue, they welcomed me into the joey clinic one morning. Dana was in the middle of individually bottle-feeding some 15 baby koalas while also caring for Connor. He was toddling around holding a branch of acacia and following the family dog, Rikku, who is remarkably tolerant of human babies and a tiny kangaroo named Kylo that likes to practice its boxing on the dog’s face. Staff and volunteers swirled in and out of the clinic, eating breakfast, getting medical supplies, asking about treatment plans. Dozens of rescued, slightly older joeys under 18 months old live in enclosures outside, since they no longer depend on milk, along with 30 older koalas with names like Ralph, Bonecrusher and Pearl; the number changes constantly as they recover enough to be released. Dana sat on a sofa cradling a baby koala they’d named Maddie, feeding it a morning bottle of Wombaroo, a low-lactose formula. When Maddie was rescued, she weighed just two pounds. “She had no burns when we found her,” Dana said, “but also no mum.”

Nearby sat Kirsten Latham, head keeper of Australia Zoo’s koala program, holding 10-month-old Duke, who was swaddled in a towel. He was rescued in January with second-degree burns and was missing several claws—which are crucial for tree-climbing—and had to be fed with a syringe before he started taking the bottle. “You have to really concentrate when you’re feeding them, as they can aspirate the milk when they’re young,” Kirsten said. “It helps to wrap them in a towel and keep a hand over their eyes, because when they’re drinking from their mums they keep their heads tucked right into the pouch, where it’s dark and quiet.” These feedings are done three times a day, and it can take each person three hours to feed all the baby koalas during a mealtime.

* * *

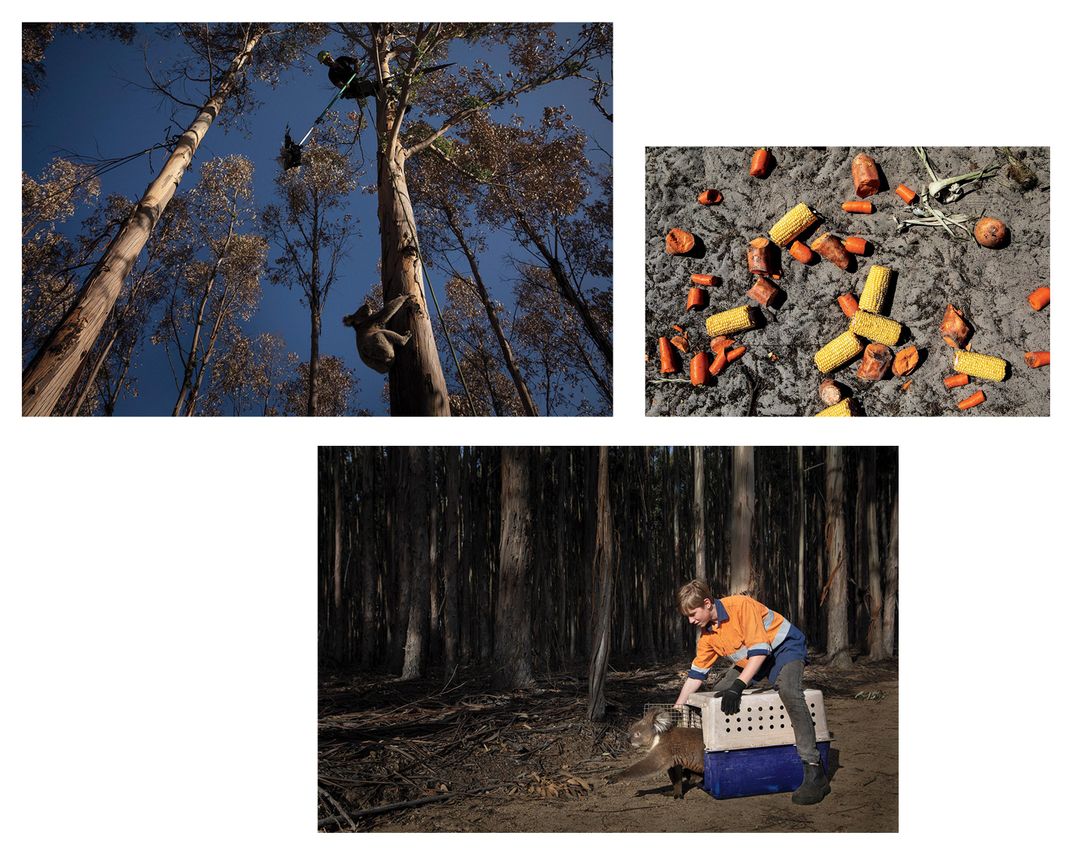

In the clinic’s kitchen, I found Kailas Wild and Freya Harvey, both fit and sunburned, wearing black T-shirts and cargo pants. They were studying a map of the island’s plantations and natural bushland, planning their next koala rescues. They are old friends and skilled climbers, and have been on the island for weeks, doing the dangerous work of climbing the tall, burnt blue gum trees to reach koalas perched at the very top, sometimes as high as 80 feet.

Kailas is an arborist and volunteer for the State Emergency Service in New South Wales, and Freya is currently based in New Zealand, but they both dropped everything to go to Kangaroo Island as soon as they realized their tree-climbing skills could help save wildlife. Kailas drove the 900-odd miles from Sydney to the ferry terminal in Cape Jervis in his pickup truck, sleeping in the back along the way, and bringing it across to the island on the ferry. It took them a little while to earn Sam’s trust; his classic Australian suspicion of “blow-ins” has been compounded by having been let down by others who turned up offering help but haven’t followed through. But now that they have it, I can see the three of them have formed a close-knit team, daily coordinating koala rescues and treatment.

The ground rescue crew that Kailas and Freya have been working with is a local family of four: Lisa and Jared Karran and their children, Saskia and Utah. They live near Kingscote, where Jared is a police officer. They’ve spent almost every day since the fires out in the bush rescuing animals. At first, the ground was so hot it was smoking, and they had to wear special boots so the soles didn’t melt. Now the risk is falling trees. They work up to 12 hours a day, the kids uncomplaining and involved, outfitted with gloves and hard hats, handling the koalas like pros, and accompanying Jared for long drives at the end of each day to release rehabilitated survivors into a distant unburned plantation. As of last count, they’ve helped rescue 143 koalas.

Outside the clinic, in a nearby field, a Robinson R44 helicopter had just landed after an aerial survey using a thermal-imaging camera to locate koalas by detecting their body heat; this is one of several ways that Sam and the rescue team are now experimenting with technology to find where koalas are clustered and whether those habitats are burned or still viable. Sam was paying a lot to rent the helicopter, and the results have been promising, but Sam is still learning how to operate the infrared camera from the air—it’s no easy feat to adjust the focus and pan-and-tilt speed while fine-tuning koala heat signatures from inside a moving helicopter—and the data is complicated to interpret.

At this phase of the recovery effort, the goal is no longer strictly to rescue injured koalas and get them to the hospital for treatment. The team is also trying to figure out if koalas remaining in the wild have enough food to survive. The fear is there will be a second wave of koala deaths, from starvation. The team is also experimenting with drones, and Thomas Gooch, founder of a Melbourne environmental analytics firm called the Office of Planetary Observations, has donated recent satellite-observation maps that display vegetation cover to identify areas that have burned.

A newer member of the koala rescue team is Douglas Thron, an aerial cinematographer and wildlife rescuer from Oakland, California, who was brought to the island by Humane Society International. In the 1990s, Thron used to take politicians and celebrities up in a little Cessna to show them the impact of clear-cutting old-growth redwood forests in California. Last year, he spent months after California’s devastating fires, and in the Bahamas after Hurricane Dorian, using a custom-made drone to spot dogs and cats trapped in the debris.

Douglas had been on the island since late February, using his drone—configured to carry an infrared camera and a 180x zoom lens and spotlight—to help the team identify where in the vast acreage of burnt blue gum plantations there were koalas needing rescue or resettlement. So far, he had spotted 110, of which 60 had been rescued.

Douglas, Kailas and Freya had spent most of the previous night in the bush, using the drone to do thermal imaging and closer spotlighting of the treetops in the darkness, when it’s easier to see the koalas’ heat signatures. From the ground, Douglas used a video screen attached to the drone controls to identify ten koalas in one section of a burnt eucalyptus plantation. Today, it would be up to the ground rescue team to head out and see what they could find by daylight.

* * *

“We were calling it Pompeii,” said Lisa Karran as we drove past a tragic tableau of carbonized Tammar wallabies huddled in a clearing beside rows of burnt blue gums. The hardest part, she said, was seeing the incinerated family groups together—baby koalas holding onto branches beside their moms, dead possums and kangaroos with their young beside them.

Standing amid rows of charred trunks, Utah, who is 13, was readying the koala pole—an extendable metal pole with a shredded feed bag attached to the end, which the climbers shake above the koala’s head to scare it down the tree. Saskia, who is 15, held the crate at the base of the tree. Jared had spotted this particular koala—“because I’m koalified!” he joked—curled right at the top of a black trunk with no leaves.

The luminous epicormic growth was sprouting from many of the trunks around us. The rescue team had begun to wonder if this growth, which is known to be more toxic than mature leaves, as the tree’s natural defense against insects and animal browsing while the tree itself struggles to survive, might be making the koalas sick. Some of the koalas they’d seen eating it, and had subsequently brought in for treatment, had diarrhea or gut bloat. They’d also observed koalas eating dead leaves rather than epicormic growth, suggesting the animals may not find it an ideal food source. Koalas are naturally adapted to the toxins in eucalyptus leaves, with gut flora that help digest the leaves and flush out the toxins. But the higher toxicity levels of the new growth may be beyond their tolerance. Ben Moore, a koala ecologist at Western Sydney University, said that there are no detailed studies that directly compare the chemical makeup of epicormic growth with adult leaves, but he hypothesized that any dramatic change in a koala’s diet would change that individual’s microbiome, and in turn affect its gut function.

In recent weeks, the group has rented a mechanized crane, which makes it easier to get to the tops of the trees, but there are still many rescues where the koala is so high up that Freya or Kailas need to clip in and use the arborist’s technique of throwing a weight and line to climb the burnt and brittle trees, and then shake the koala pole above the animal’s head. Typically, a koala grunts or squeals and climbs down a trunk amazingly fast. After Lisa or Utah plucks it off the trunk at the bottom and places it in a crate, it becomes surprisingly docile, gazing up at its human saviors.

The first koala rescued that day was underweight, and others had pink patches on their feet signaling healing burns, but some were healthy enough, the group decided, to be released elsewhere without needing to be checked by vets at the Wildlife Park.

Hours and hours passed like this in the hot plantations. It was gripping to watch. Each rescue had a unique emotional texture—a dramatic arc of growing tension as those on the ground waited for the climbers to encourage the koalas down, the adrenaline spike of grabbing the animals behind their strong necks and getting them into the crate, and the communal relief if they were found to be healthy. Each of the ten koalas rescued that day was found almost exactly where Douglas’s drone had spotted them the night before.

During one rescue, a koala kept up a plaintive high-pitched wail but would not budge from its perch. Freya and Kailas both had to clip in and climb up in order to coax it down. Once on the ground the team knew this koala was seriously unwell: its paws were covered in fresh blood, from the loss of several claws—a sign of previous burns or infections. Kailas, in particular, was devastated, and sobbed openly. They knew from experience what fate awaited this koala. Later that night, after its condition was checked at the Wildlife Park, it was euthanized.

The next day, Kailas made his 100th rescue. It also happened to be Jared’s last day doing rescues with his family. The next Monday, he’d be back at work as a police officer. “There’ll be criminals robbing the bank, and I’ll be gazing up into the trees, looking for koalas,” he said wistfully. He’d been scrolling back through his photos, and had been struck by a picture of Saskia and Utah swimming in the sea the day before the fires started, two months before. “Every day since, it’s just been so different,” he said. “I was thinking this morning that I want to get back to that.”

At dusk, the Karrans drove out to one of the only plantations that didn’t burn, called Kellendale. They had six healthy koalas in the back seat and the trunk of their SUV, rescued from plantations with no leaf cover for food. After the eerie silence of another long day spent in burnt plantations—not a single insect hum or bird song—it was a joy to see a flash of pink from the belly of a rose-breasted cockatoo, and to hear the soft, wavelike rustling of living eucalyptus leaves in the breeze. It felt like paradise.

Utah and Saskia released the koalas from their crates one by one, and the family laughed together as one of their feistiest rescues, a female koala with lovely fluffy ears, sprinted for a tree, climbed about 15 feet up, then stopped and stared back down at the humans for a good long while. Then she climbed higher, cozily wedged herself in the fork of a branch, and held on tight as the narrow trunk rocked in the wind.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/92/25/9225940c-78ab-4885-929a-2f1070c5db68/mobileopenerjun2020_c16_kangarooisland_copy_2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/90/76/907608b9-9a4b-414e-b49d-c980217c9131/openerjun2020_c16_kangarooisland.jpg)