Seduced By a Rare Parrot

What can conservationists learn from New Zealand’s official “spokesbird,” a YouTube celebrity who tries to mate with people’s heads?

:focal(1320x1604:1321x1605)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c4/27/c427ec0a-c43a-4f03-b732-c15b8a139d75/sirocco.jpg)

Wanted: One of New Zealand’s most beloved celebrities.

Name: Sirocco.

Distinguishing features: a loud booming voice, very sharp claws and bright green feathers.

Admittedly, Sirocco is a parrot—but not just any parrot. He's one of just 154 members of the critically endangered kākāpō parrot species, found only in New Zealand on a series of secluded islands. And even in that rarified group, Sirocco is unique: In 2010, former Prime Minister John Key dubbed him the nation’s “official spokesbird for conservation.” You may recognize the avian advocate from his breakthrough moment the year before, when he was caught on camera trying to mate with zoologist Mark Carwardine’s head.

A star from that moment on, Sirocco has since gone on annual nationwide tours as ambassador for his species. He promotes various wildlife conservation issues through his official Twitter and Facebook accounts, which have amassed thousands of followers. (A skraaarrrk! or a boom!—the strange, evocative noises of kākāpō—precedes every post.) He has even visited New Zealand’s parliament to meet politicians and promote the achievements of the Kākāpō Recovery Program, which the Department of Conservation launched in 1990 to save the birds from the specter of extinction.

Sirocco still spends the vast majority of his time on his human-less island, where scientists monitor him through a transmitter that tracks his every move. Unfortunately, these transmitters aren't fail-safe; about 5 percent fail annually. That seems to be what happened last year, when Sirocco went off the grid for the first time. Authorities spent months quietly conducting periodic searches for him using trained English setters, but finally gave up and issued a public statement in March just before his 20th birthday, or "hatchday."

The celebrity bird, it seemed, would be partying solo this year.

What’s more fascinating than Sirocco’s current disappearance, however, is his runaway success in the role of spokesbird. Like other charming animal icons—think Bao Bao the giant panda and Challenger the bald eagle—this one plump parrot has come to represent the plight of his entire species. And that plight has resonated widely: Through his advocacy work and social media savvy, Sirocco has prompted countless people around the world to invest in the future of birds many have never seen in the flesh.

The rise of this winsome, human-loving bird raises key questions for conservationists, namely: What are the possibilities and limits of promoting such naturally charismatic animals? And how much should we worry about letting those who may be more threatened, but less physically endearing, fall by the wayside?

Kākāpō, which are sacred to Māori, were once so common that European colonists complained that their screeching mating calls kept them up at night. “They’d shake a tree, and six kākāpō would fall out, like apples,” says Andrew Digby, a science advisor on the kākāpō recovery team.

With colonization, these numbers quickly plummeted. Invasive stoats and cats snacked on the parrots; humans hunted them for their meat and feathers, or tried to keep them as pets. In 1995, researchers counted only 51 surviving kākāpō, which humans cared for on predator-free islands. Yet that precarious number has grown threefold in Sirocco’s lifetime—thanks, in part, to his successful ambassadorship. Last year witnessed a 24 percent increase in numbers, making for the best breeding season yet.

The world’s only flightless and nocturnal parrots—and the heaviest—kākāpō are real oddities. They’re skilled at tree-climbing and have powerful thighs for walking long distances, making them well-adapted to their particular environment. But they also have high infertility rates and breed only every two or three summers, depending on the levels of nutritious rimu berries, meaning they’re challenged with chick-making.

Sirocco may be the oddest kākāpō of all. Hand-raised by rangers due to respiratory issues, he imprinted on humans at an early age, and swore off mating with his own kind. (Hence his session with Carwardine, who was far from the first or last to be, as Stephen Fry quipped in that video, “shagged by a rare parrot.”)

Male kākāpō who are ready to mate dig bowls in the ground, where they sit and inflate themselves, like footballs, as they boom all night to attract females. Sirocco builds bowls and booms near humans. When he resided on Codfish Island (his current island home must remain unnamed, to protect the sanctuary) he settled near an outhouse and chased people en route to relieve themselves. Researchers erected a fence by the hut to stop him from crawling up legs to get to their heads.

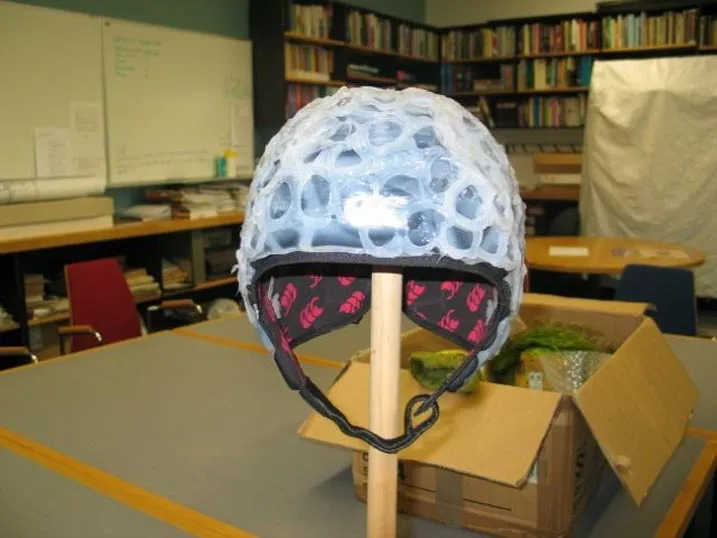

Head-mating is a common theme with Sirocco. He has tried to mate with heads so often that scientists once fashioned an “ejaculation helmet” for volunteers to don. The rubber headgear features an array of dimples to collect semen—essentially, a hat of condoms. It never worked, as kākāpō are intense at intercourse, doing it for close to an hour while most birds require just a few seconds. The helmet now resides in Wellington’s Te Papa Museum, next to “Chloe,” a motorized, decoy female kākāpō who was another failed breeding booster.

“I haven’t met anyone with the stamina or patience to let Sirocco continue for the normal kākāpō mating period,” says Daryl Eason, the recovery program’s technical advisor. “Sirocco has been the most difficult kakapo to collect semen from. He doesn’t volunteer it, and he resists the massage method that works well for most other kākāpō.”

So breeding isn’t on his CV. But Sirocco makes up for it through his advocacy work. The recovery program may be the planet’s most geographically isolated, but it receives an incredible amount of international attention. In fact, most donations arrive from overseas. A surprise $8,000 pledge came last month, from its highest-profile donor yet: Google. The money could fund a year’s supply of supplementary feeding on one island.

A large part of Sirocco’s global reach stems from the viral popularity of his on-screen, unrequited affection for Carwardine—a once-in-a-lifetime fluke of television that endures online. But the Department of Conservation has effectively capitalized on that moment, subsequently publicizing Sirocco’s importance and promoting the mischievous misfit online in order to steer attention to his rarely seen kin. Most people, Digby believes, learn about kākāpō through Sirocco’s distinct social media presence.

The social media team keeps him well in the public sphere, posting news on Twitter and Facebook as a personified Sirocco who relays colorful updates. (You can even download a series of "party parrot" emojis based on Sirocco, here.) The parrot's posts, silly as they can be, present a personality that captures our imaginations: a bird who is awkward and weird, yet endearing and caring of wildlife. And they offer a promising model for other recovery programs to spotlight certain animals as animated characters who can connect with our own personalities—even if some scientists may feel uneasy about the idea.

“The anthropomorphizing was a risk, and was a slight concern,” says Digby. “But it's proved to be a big success. I also think there's a danger in trivializing the kakapo's plight, especially with the whole Sirocco shagging thing, but I don't think that's happened … It's the ‘human’ characteristics of Sirocco—and kākāpō—that many people find appealing, so anthropomorphism is appropriate in this case as an advocacy tool.”

Some argue that sponsorship of charismatic animals, which tend to be high-maintenance (think Bao Bao), is an inefficient use of money. We could save more animals, they say, if we directly supported less costly species that face graver threats—and may even be more beneficial to their ecosystems. According to Mike Dickison, a curator of natural history at the Whanganui Regional Museum, saving a bird costs ten times as much as saving a critically threatened beetle. But bugs, sadly, aren’t great at scoring social media likes. Nor are New Zealand’s endangered earthworms, leeches or lichens.

Others point out that creatures who live in the same ecosystem as flagship species will benefit as a trickle-down effect, as many of these large creatures form key pillars of their environments. As Dickison says, this effect exists, but it’s trivial compared to that of allocating money to more species with cheaper upkeeps than, say, kākāpō.

Trickle-down benefits asside, the kākāpō recovery program has made concrete strides for animals outside of this spirited psittacines (the order of birds that includes parrots) it supports. In fact, the recovery team has pioneered technologies that other wildlife conservation programs have adopted, from transmitters that detect mating and nesting activity to automatic feeding stations.

Artificial insemination is one such effort: in 2009, the team celebrated the first-ever successful AI attempt on a wild bird species. “The kākāpō team pushes the boundaries a little bit,” says Digby. “From a conservation point of view, a lot of the stuff we do, no one’s done before.”

This February, the team began an ambitious project to sequence the genomes of every living kākāpō, another historic first. The results will answer many lingering questions about the parrots, perhaps confirming that kākāpō are one of the world’s longest-living birds. (Scientists believe they live on average 60 years, but Digby says he wouldn’t be surprised if that number reaches up to 90, or even 100 years.) Most significantly, the full pedigree will guide breeding strategies to ensure that the next generation of kākāpō are as genetically fit and diverse as possible.

Now, the team is working with Weta Workshop—yes, of Lord of the Rings fame—to produce eggs fitted with smart technology to make them chirp and move like actual, soon-to-hatch eggs. These, if realized, will sit in nests as the real ones safely incubate elsewhere, as mothers sometimes crush their eggs. Come hatch-time, scientists will swap out the dummies, and Mom, ideally, will be alert to the imminent arrival of a chick. In short: We’ve come a long way from Sirocco’s ejaculation helmet.

…

So what of Sirocco, our missing Kakapo?

While undoubtedly an important individual, researchers aren’t too concerned about his missing status at the moment. After all, he lives on an island with no natural predators and cannot fly. Searches are tedious and pricey, so his rangers are waiting until the next mating period, when high testosterone levels will make him once again seek out humans and their heads. It’s taken as long as 14 and even 21 years to relocate kākāpō in the past, but Eason believes Sirocco will appear again within two to three.

Of course, his presence will be missed. The kākāpō, who is still receiving birthday messages from overseas, has his next scheduled public appearance in September, at Dunedin’s Orokonui Sanctuary. If he’s still unaccounted for by then, his duties may go to his three-year-old sidekick, Ruapuke, who is far less seasoned in greeting kākāpō fans and has no beloved reputation for mating with heads.

In the meantime, count on Sirocco to boom loudly online, for kākāpō and many others—from monk seals to conservation dogs to earthworms—with surplus charm and unending charisma.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c4/27/c427ec0a-c43a-4f03-b732-c15b8a139d75/sirocco.jpg)