Seven Species You’ll See Only in Pictures

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20110520102306dod-241x300.jpg)

While writing about the Falklands wolf last week and earlier about the Labrador duck, I was reminded that they are only two of the dozens, maybe hundreds, of creatures that have gone extinct in recent human memory (that is, the last few hundred years). Here are seven more creatures that exist only in pictures or as museum specimens:

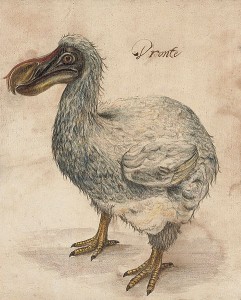

Dodo (Raphus cucullatus)

The dodo has become synonymous with extinction. To "go the way of the dodo," for example, means that something is headed out of existence. The three-foot-tall, flightless bird lived on the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. They probably ate fruit. Though the birds did not fear humans, hunting was not a huge problem for the birds as they didn't taste very good. More troublesome were the other animals that came with people—like dogs, cats and rats—that destroyed dodo nests. Human destruction of their forest homes was also a contributor to the dodo's decline. The last dodo was seen on the island sometime in the late 1600s.

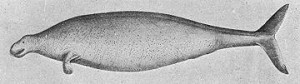

Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas)

Georg Steller first described his sea cow in 1741 on an expedition to the uninhabited Commander Islands off the coast of Kamchatka. The placid sea creature probably grew as big as 26 feet long and weighed around 8 to 10 tons. It fed on kelp. Just 27 years after Steller's discovery, however, it was hunted to extinction.

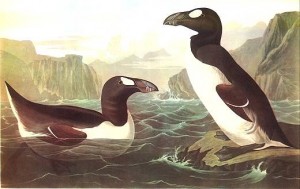

Great auk (Pinguinus impennis)

Millions of these black-and-white birds once inhabited rocky islands in some of the coldest parts of the North Atlantic, where the sea provided a bounty of fish. Though their population numbers probably took a hit during the last Ice Age, it was the feathers that kept them warm that led to their downfall. The soft down feathers were preferred pillow filling in Europe in the 1500s and in North America in the 1700s. The dwindling birds were further doomed when their eggs became a popular collector's item. The last live auk was seen in Newfoundland in 1852.

Passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius)

The passenger pigeon was once the most numerous bird species in North America, making up 25 to 40 percent of all birds on the continent. There were as many as 3 to 5 billion of them before the Europeans arrived. They would migrate in huge flocks consisting of millions of birds. In the 1800s, however, they became a popular food item. Tens of thousands could be killed in a day. By the end of that century, when laws were finally passed to ban their hunting, it was too late. The last wild bird was captured in 1900. Martha, the last of her kind, died in 1914 at the Cincinnati Zoological Garden.

Carolina parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis)

The eastern United States once had its own native parrot, the Carolina parakeet. But farmers cut down their forests and made fields, and then killed the birds for being pests. Some birds were taken so that their feathers could adorn ladies' hats, and others became pets. The last wild parakeet was killed in 1904 in Florida. The last captive bird, which oddly enough lived in the same cage in which the passenger pigeon Martha died (above), died in 1918.

Tasmanian tiger, a.k.a. the thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus)

The thylacine wasn't really a tiger, though it got that name for the stripes on its back. The largest carnivorous marsupial, it was once native to New Guinea, Tasmania and Australia. It had already become rare by the time Europeans found Australia, confined to the island of Tasmania. In the 1800s, a bounty was put on the species because it was a danger to the sheep flocks on the island. The last wild thylacine was killed in 1930, though some may have survived into the 1960s.

Golden toad (Bufo periglenes)

They lived in the Monteverde Cloud Forest Preserve in Costa Rica. Most of the year, they were hard to find, and scientists think they may have lived underground. But during the rainy season of April to June, they would gather in small, temporary pools to mate. The population crashed in 1987 due to a bad patch of weather and none have been seen since 1991. No one is sure what happened, but climate change, deforestation and invasive species have all been suggested as possible culprits.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)