Sharks Made Out of Golf Bags? A Look at the Big Fish in Contemporary Art

Intrigued by the powerful hunters, artists have made tiger sharks, great whites and hammerheads the subjects of sculpture

Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In 1991, British artist Damien Hirst stuffed a 13-foot tiger shark, caught in Australia, and mounted it in a 4,360-gallon glass tank of formaldehyde. Charles Saatchi owned the work, titled The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, until 2004, when he sold it to art collector Steven Cohen for a whopping $12 million. Cohen loaned the piece to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2007, where it remained on display in the modern and contemporary art wing for three years.

“While the shark was certainly a novel artistic concept, many in the art world were uncertain whether it qualified as art,” writes marketing and economics professor Don Thompson, in his book, The $12 Million Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art. “The question was important because $12 million represented more money than had ever been paid for a work by a living artist, other than Jasper Johns,” he notes.

Many claimed that the sculpture required no artistic skill. They felt that anyone could have created it, and, to this, Hirst had an obnoxious-yet-valid response. “But you didn’t, did you?” he’d say.

Hirst later pickled a great white in The Immortal and bull sharks in Theology, Philosophy, Medicine, Justice. For Dark Rainbow, he made a resin cast of a tiger shark’s gaping jaw and painted its chompers bright colors.

There is something about sharks. People are fascinated with them, and artists are certainly no exception.

A year after Hirst created The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, Robbie Barber, an artist and professor at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, bought a pink golf bag at a thrift store. “As an artist, I have always been interested with found objects,” he says. Barber stared at it for days, pondering how he might use it. “It wasn’t until I hung it horizontally from wires, as if it were floating, that I ‘saw’ the shark image in my mind,” he explains.

The self-described “junker” collected more golf bags from flea markets and thrift stores. The golf bags became the bodies of great whites, hammerheads and blue sharks. Barber fashioned steel armatures inside the bags and carved heads, fins and tails out of wood. All the while, he referred to scientific images and illustrations for accuracy. His great whites have “large gashes” for mouths, he says, and the hammerheads have “small, little trapdoor-like openings.” To the ten shark sculptures he made from the golf bags, he added baby sharks built from dust busters and crabs from toasters to complete a mixed media installation called The Reef.

“When I created these , I was specifically thinking about the effects of humans on the environment, and how animals have to deal with our trash dumping tendencies,” says Barber.

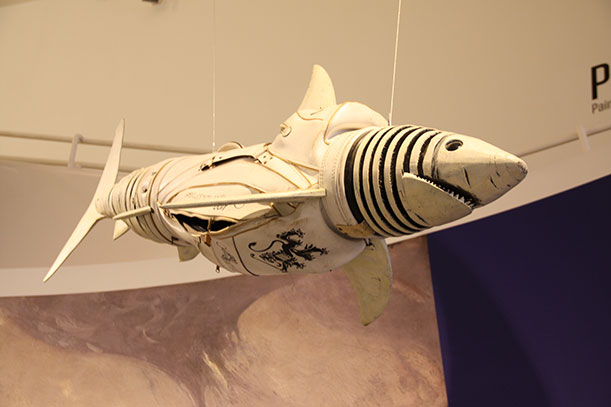

In 2008, a camping trip on Cockatoo Island in Australia’s Sydney Harbor inspired Vancouver-based artist Brian Jungen to construct a 26- by 20-foot mobile called Crux. The night sky was filled with constellations and air traffic from Sydney International Airport. Melding the two, Jungen sculpted animals from torn-apart luggage, mirroring what Australia’s indigenous aborigines saw in constellations. He created a shark (above) with fins hewn from the hard, gray exterior of a Samsonite suitcase.

Barber, Jungen and Massachusetts-based artist Kitty Wales are kindred spirits in their fondness for found objects and sharks. As an artist, Wales takes a special interest in the anatomy and movement of animals. She actually observes her subjects in the wild. For Pine Sharks, an installation at the DeCordova Sculpture Park in Lincoln, Massachusetts, Wales called upon an experience diving with sharks in the Bahamas. She had a plastic slate with her, while underwater, and she sketched the sharks from life. Then, back in her studio, she sculpted three swimming sharks from old appliances—again, a commentary on our wasteful tendencies. The shark named “American Standard” is a repurposed oil burner. “Maytag” is built from a refrigerator, and “Hotpoint” is welded from scraps of a mid-century, olive-green stove.

For more shark-inspired art, I highly recommend the book, Shark: A Visual History, by esteemed marine artist Richard Ellis.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)