A Shipwreck Graveyard Has Been Found Off This Greek Archipelago

A recent expedition to the Fourni islands uncovered piles of ancient cargo, including types of amphorae never before seen on the seafloor

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/00/1f/001fcdf0-5aa0-498b-9b30-7f2d42f048de/a_small_amphora_for_luxury_goods_by_v_mentogianis.jpg)

For underwater archaeologists, even a few shards of ancient pottery can count as buried treasure. But sometimes, explorers hit the artifact jackpot.

A joint Greek-American expedition announced this week that they have just uncovered a whopping 22 shipwrecks around the Fourni archipelago—a find they say adds 12 percent to the total number of known ancient shipwrecks in Greece.

The newfound wrecks include cargo that dates from the Archaic Period (700 to 480 B.C.) all the way up to the 16th century, and the team says the finds could change the way historians think about ancient Greek trade. For instance, some of the amphorae styles found around the wrecks have never been seen before on the seafloor.

“We knew some of these amphora types existed from fragmentary evidence on land, but we’d never found them as a wreck before,” says expedition member Peter Campbell, co-director of the RPM Nautical Foundation. The American maritime research non-profit collaborated with the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities on the recent shipwreck hunt.

The Fourni archipelago is a small set of islands, islets and reefs that lies in the northeastern Aegean Sea, in the triangle formed by the Greek islands of Ikaria, Samos and Patmos. The region sits in the middle of a shipping channel that was thought to have been an important maritime corridor during antiquity.

Though the archipelago itself wasn’t a destination for traders, it did become the final resting place for plenty of ships buffeted by sudden southern storms as they made their way from Greece to Cyprus and Egypt. Once the expedition began, Campbell says the crew just kept finding wrecks.

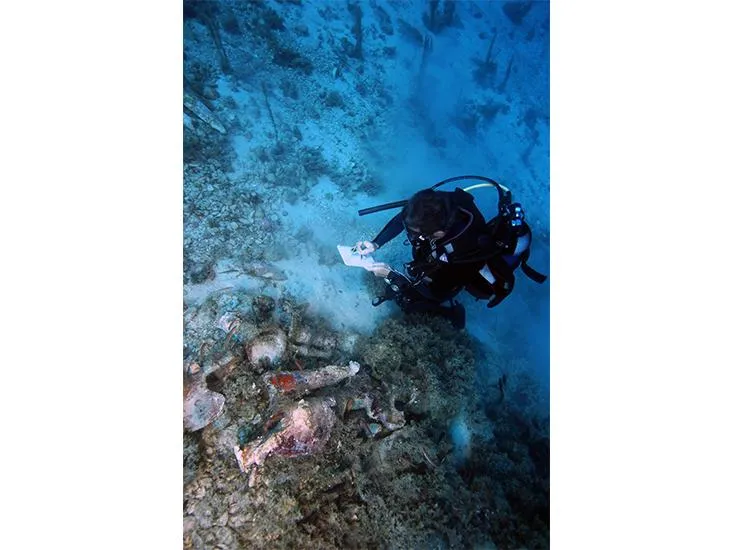

"If we hadn’t stopped, we would have hit 30 or 40 in a few weeks,” he says. Campbell and his team documented each wreck in 3D then brought up representative samples for study.

The archipelago is rocky, and over the years water has destroyed most of the vessels' material that wasn’t torn apart during the wrecks, so there weren’t too many ship remnants to speak of. Instead, the team found mostly cargo, including large troves of amphorae—handled jars that were common containers in ancient Greece and Rome.

Like the ubiquitous plastic bottles and glass jars we use today, amphorae transported a range of goods during ancient times, from water and wine to oil and fish sauce. But their size, shape, materials and other distinctive marks can offer clues to their contents. So while they may already be plentiful, any large body of amphorae can help archaeologists track ancient shipments.

“We know where amphoras were made and when they were made, so they can help paint what some of the major trade routes were over time,” says Mark Lawall, an expert on Greek transport amphorae who was not on the expedition team.

Over the years, for instance, amphorae have helped build the case that Greek trade involved “huge ships and highly structured financial systems to support that shipping,” says Lawall.

Among the more unique finds from Fourni were rare teardrop-shaped amphorae from Samos dated to the Archaic Period, four-foot-tall fish sauce amphorae from the Black Sea region that date to the second century A.D., and carrot-shaped amphorae from Sinop, thought to date to the third to seventh centuries A.D.

“It was quite exciting to find actual wrecks carrying these—very exciting and very rare,” Campbell says.

But Lawall warns that since shipping vessels were often reused, it can be hard to accurately track their progress and sort out just how many distinct wrecks exist in a certain spot.

“These ships were very much international melting pots,” Campbell agrees. “They might have had wood from Lebanon, fasteners from Greece, amphoras from Levant and a crew made up of many different cultural groups.” Ships generally departed filled with amphorae from their point of origin but then acquired others as they made cargo drops from port to port—a fact that could make it hard to determine exactly where the individual Fourni ships came from.

Still, researchers think the find shows the complexity, diversity and sheer magnitude of Greek shipping through the popular Fourni corridor. Representative samples of the amphorae are now in a wet lab in Greece for preservation and further investigation. If any amphorae turn out to be particularly rare or valuable, they may go on display after careful conservation and preparation for out-of-water conditions.

But even if the general public never sees them on display, the finds have huge value, says Campbell. “A data set such as this could really change perceptions about ancient trade,” he says. And with more expeditions to Fourni planned for the future, that data set may well continue to grow.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)