Shoot-out at Little Galloo

Angry fishermen accuse the cormorant of ruining their livelihood and have taken the law into their own hands. But is the cormorant to blame?

In upstate New York on the evening of July 27, 1998, three men with shotguns put ashore on a guano-covered slab of limestone in eastern LakeOntario called Little Galloo Island. The men pointed their guns at dozens of duck-size black waterbirds perching on the branches of a pair of dead trees and opened fire.

When the branches were bare, the gunmen turned and walked the half-mile length of the island, a state-owned bird sanctuary, shooting more cormorants as they went. At the far shore, they found hundreds of cormorant chicks huddled on the ground. They shot them, too, then turned and walked back across the island, killing birds they had missed.

At the same time, two others in a boat circled the island and shot birds trying to leave. They herded birds bunched in the water back toward shore. When the men on land finished shooting, they climbed into the boat and sped back across the lake to the mainland. All told, they killed some 850 birds.

Two days later, a crew from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) approached Little Galloo on a routine visit to conduct research. As they neared the island, they were met with an unusual odor. “It was a mess,” reported Russ McCullough, a DEC fisheries biologist who went ashore that day. “There were large numbers of dead birds . . . distressed chicks . . . and spent shotgun shells.” While the magnitude of the slaughter was unusual, it didn’t take the biologists completely by surprise. From the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to as far away as Poland, shifting environmental conditions have swelled cormorant populations over the past two decades. Cohabitating humans, particularly fishermen, have not been happy about it.

Take Little Galloo. In 1974, ecologists discovered a colony of 22 pairs of cormorants nesting there. By 1984, the colony had ballooned to 8,000 pairs of the large (their wingspan reaches four and a half feet), powerful, highly efficient fisheating predators. If you think of these birds as wolves in cattle country, you’ll get an idea of how the local community views them.

It’s a matter of money. Cormorants eat fish, and people in the sportfishing industry in eastern LakeOntario and other parts of the Great Lakes say there are not enough fish to go around. They believe the cormorants’ appetites directly affect their incomes. Meetings on what to do about the problem are seldom pretty. “All cormorant meetings are yelling meetings,” says Mark Ridgway, a research scientist at the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources.

Federal investigators eventually amassed enough evidence against the men who shot the cormorants to arrest them. Four of the five men worked as fishing guides and sold bait and tackle in the small New York town of Henderson, Little Galloo’s neighbor. Afederal judge in Syracuse sentenced the men to six months’ house arrest, fined them each $2,500 and required each to make a $5,000 contribution to the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. Five other local men were given lesser sentences for earlier, less wholesale cormorant carnage and for hiding the weapons used at Little Galloo. Depending on whom you ask, the five men who went to Little Galloo were either vigilantes who got off with a slap on the wrist or heroes unfairly punished for a job that needed doing. “It wasn’t a crime,” says Tony Noche, 65, a retired cop from Syracuse who has been fishing here for 30 years. “The men had no choice. It was civil disobedience.” Craig Benedict, the attorney who led the prosecution, disagrees: “The men are more like night riders than civil rights activists.”

No one disputes that for 15 years now fishermen in Henderson have watched ever-growing numbers of cormorants gobble up lake fish amid declining incomes. But are the cormorants to blame, or are the birds scapegoats for large-scale environmental changes affecting the Great Lakes?

“So are you for the cormorants or against them?” asks a young woman I met in a state park just outside Henderson, a town of 5,000 about an hour’s drive north of Syracuse. The chatty teenager looks like the kind of person who might volunteer for Greenpeace if she were living in Seattle. But this is Henderson, where people eat, drink, breathe and sleep fishing; there is only one view of cormorants here: “They don’t have a place in the ecosystem,” she insists. “They eat up the native bass, and their feces have parasites!”

It’s late June. The peonies are spent, and the last mock oranges perfume the air. Lawn chairs are pulled up to the water’s edge. Bass-, salmon- and trout-fishing seasons have opened. Fifteen years ago, before the cormorant population exploded, the town was a different place, says Jerry Crowley, a mechanic, as he tinkers with a boat engine. “Instead of working on my boat this time of year, I would have been up in the office, answering the phone and working the cash register. The cormorants have turned this place into a ghost town. Do the math! Those birds will eat a pound of fish a day. How many are out there on that island? Five thousand pairs?”

Henchen’s Marina, just down the waterfront, features a whole line of anticormorant paraphernalia, from T-shirts and decals to bumper stickers and pennants. The most repeated image is a red slash across the drawing of a cormorant inside a red circle. Initially, profits from the sale of these items helped pay the fines of the ten men convicted in the cormorant massacre. Now the money goes to Concerned Citizens for Cormorant Control, a local group directed by longtime bass-fishing guide Ron Ditch, who was convicted in the cormorant shootings along with three of his four grown sons.

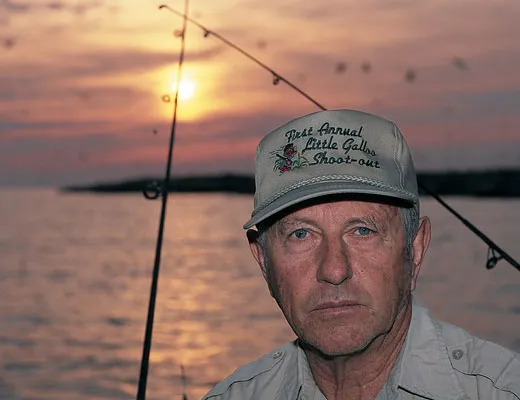

Ditch, 67, a sinewy man with piercing blue eyes, wears a baseball cap that reads “First Annual Little Galloo Shoot-out.” Lettering on the back of the hat, just above the plastic strap, announces the score: Fishermen 850, Cormorants 10. The cap is a present from Ron’s wife, Ora, 67, a snowy-haired woman with a whiplash sense of humor who seems 20 years younger than Ron, although they met the day they both started ninth grade and were married six months after they graduated from a high school outside Syracuse.

Ron and Ora Ditch own and operate a marina at the far end of town. Ron has agreed to be interviewed only on the condition that I go fishing with him. At 9 a.m., he shuts off the engine of his 27-foot SportCraft, and we drift by Big Galloo, about a mile from Little Galloo. He casts his baited hook with the lazy perfection of a major league pitcher lobbing a ball to a child. As he talks, his fingers twitch and creep on the handle of his rod as if he were communicating with the bass circling the bait below. He pulls in a dozen or so bass, twice as many as the other anglers in the boat.

Ditch believes himself an upright man pushed beyond endurance. “The cormorants were having a multimillion dollar impact,” he says. “If something hadn’t been done, this whole area would have been a wasteland. We couldn’t shoot them fast enough.”

As we circle the island, he tells me about how he used to bring clients here in the old, pre-cormorant days. They’d catch their legal limit of five bass each in the morning, put ashore, cook up the fish for a hearty lunch, then go out and catch the limit again in the afternoon. “Now, because of the cormorants, the fish are gone,” he says. “This place will never go back to being what it was.”

In fact, lakeOntario has been changing for 200 years, ever since the War of 1812 made the Great Lakes’ shores safe for American settlers, who moved here in droves. Back then, the lake held the world’s largest landlocked population of Atlantic salmon, so many that people could wade into the water and pitchfork them onto shore. But the settlers threw milldams up across major tributaries, which kept the salmon from their spawning grounds, and cut down trees, causing the wetland to dry up. By 1860, the salmon were gone.

In the 20th century, untreated sewage and wastewater, phosphate-rich runoff from farms, DDT, PCBs, mercury, dioxin, cadmium and other pesticides, herbicides and industrial wastes began to enter the lakes. Small organisms such as plankton take DDT and other toxins into their systems and pass them up the food chain. In the 1960s, scientists found DDT concentrations in fish-eating birds one million times the amount in the water. The high levels of DDT caused birds to lay eggs with eggshells too thin to support the weight of incubating adults. From the late 1950s to the early 1970s, cormorants, bald eagles, osprey and other fisheaters in the area had little success reproducing. Pretty soon the birds were almost gone.

Into this situation swam a little plankton-eating baitfish called an alewife, which found an ideal habitat in the plankton-rich, nearly predator-free waters of LakeOntario. The tiny fish prospered. By the 1950s, so many alewives would wash up onshore they had to be cleared away with backhoes. This abundance led DEC fisheries biologists to conclude that the lake could support some new sport fish species to boost the local economy and reduce nuisance levels of alewifes. In 1968, they began stocking the lake with Pacific salmon—chinook and coho—and a kind of char known as lake trout. Anglers from all over the world came to towns like Henderson to catch them. In 1988, visitors spent more than $34 million on fishing and fishing-related activities in JeffersonCounty, which includes Henderson. This despite DEC fishing regulations warning anglers that the larger salmon and lake trout are so heavily contaminated with toxins they shouldn’t be eaten more than once a month. (Brown trout over 20 inches, lake trout over 25 inches and all Chinook salmon and carp are too contaminated to eat.)

As DEC biologists started stocking fish, events outside the state were beginning to exert profound changes on the Great Lakes. In 1972, DDT was banned nationwide, a response in large part to the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962. In 1969, the oily waters of Ohio’s CuyahogaRiver caught fire and burned; towering flames reached five-stories high and helped trigger passage, in 1972, of the Clean Water Act. The results were dramatic: by the mid-’70s, Lake Ontario had cleared up so much that the eggs of fish-eating birds had begun to hatch once again.

Enter the cormorant, a sinuous dark bird with the vulturine habit of perching with wings outstretched, feathers like laundry hung on a line to dry. (In fact, it spreads its wings to dry them; the cormorant’s feathers lack the waterproofing of many other waterbirds, an adaptation thought to enhance performance when it dives for fish.) Humans have long recognized the comorant’s fishing prowess: some 1,300 years ago, the Japanese perfected ukai, a method of river fishing using cormorants on leashes. A small metal ring fitted around the neck of each cormorant prevents it from swallowing the fish it captures. That same fishing skill had earned cormorants the enmity of fishermen long before the incident at Little Galloo. Environmentalist Farley Mowat noted in 1984 that Canadian fishermen at the turn of the 20th century blamed the cormorant for declining fish stocks in the Great Lakes. “This led to a deliberate attempt to wipe them out,” he wrote in Sea of Slaughter, “chiefly by raids on their rookeries during which all eggs and chicks would be ground under foot and as many adults as possible shot down.” This campaign proved so successful, he wrote, that “by 1940, fewer than 3,000 great cormorants existed in Canadian waters.”

Of some 30 species of cormorant in the world, two species predominate. The greater cormorant, Phalacrocorax carbo, which ranges from the northeast coast of the United States across Europe and into Africa and Southeast Asia, plagues European fisheries. Little Galloo is home to the double-crested cormorant, Phalacrocorax auritus, named for a pair of cowlicks that make a brief appearance on males at the start of the breeding season (see photograph, p.3).

The double-crested variety winters in the southern United States, where thousands of acres of accessible catfish farms may have contributed to the bird’s astronomical population growth. “It could be that the fish farms get the young cormorants through that crucial first winter, thus greatly increasing survival rates,” says ecologist Gerry Smith of Copenhagen, New York. In addition, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1972 protects cormorants by making it a federal offense to shoot them, take their eggs or destroy their nests. Then, too, says cormorant expert Chip Weseloh of the Canadian Wildlife Service, “Bird populations do make eruptions and start to spread for no apparent reason. Overfishing disrupts whole ecosystems and may contribute to increases in cormorant numbers.” Weseloh means overfishing by humans, of course. But it’s humans who accuse the cormorant of overfishing.

By the late 1980s, LakeOntario fishermen were asking the DEC to do something about the bird’s role in declining fish populations. After studying the matter, the DEC in 1998 concluded that while cormorants do feed on yearling lake and brown trout, they don’t eat salmon or adult lake trout, which live in water too deep for them to reach. When fishermen complained that cormorants were eating too many alewives, depleting salmon and lake trout by depriving them of their major source of food, the DEC commissioned more studies. In 1999, the agency published a report asserting that the greater culprit in the decline of alewives was the zebra mussel, a modest-looking little bivalve from the Caspian Sea that infested the Great Lakes in the mid-1980s after stowing away in the ballast water of tankers and other merchant ships.

The zebra mussel’s meteoric rise makes the alewife empire look puny. Today, zebras cover much of the bottom of LakeOntario, in some places as thickly as 50,000 per square yard. Although no larger than a thimble, a single mussel can remove all the plankton from a quart of water every day. Together, the Clean Water Act and the zebra mussel have transformed the algae- and plankton-rich waters into a lake so clear that visibility now often exceeds 25 feet.

During the 1990s, Little Galloo’s cormorant population spiked to some 25,000 birds, then spread to neighboring islands. Fishermen watched helplessly as growing numbers of the birds dived into the water and emerged with fish. At the same time, smallmouth bass fishing wasn’t what it used to be. The local economy slowed. Soon, anticormorant senti ment, and tension, mounted. More yelling meetings took place. “Biological science, hell,” Clif Schneider, a retired DEC fisheries biologist snorted. “What you need here is a degree in political science.”

Money spent on sportfishing in the eastern LakeOntario area fell 18 percent between 1988 and 1996, according to a 2002 CornellUniversity study. But Tommy Brown, its lead author, says negative media publicity and fewer plankton probably had as much to do with the decline as the cormorants. “And for some anglers,” he adds, “the novelty of Great Lakes fishing, especially for salmon and lake trout, simply may have worn off.” (In fact, fishing’s allure has lost luster nationwide. A 2001 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) survey suggests that the number of days individuals 16 and older spend fishing each year declined nearly 44 percent between 1985 and 2001.)

Under pressure from local fishermen in the mid- 1990s, the DEC obtained permits from the FWS to knock down nests on other islands and to curb the population on Little Galloo. But before DEC acted on Little Galloo, a new study, begun in 1998, suggested that the cormorants were indeed depleting smallmouth bass stocks in eastern LakeOntario. DEC proposed oiling the eggs, which suffocates the embryos, and, if necessary, shooting adults. They set a target of 1,500 pairs for Little Galloo. But by then the Henderson shooters had already loaded their shotguns.

On little galloo the smell of ammonia is strong. Gulls whirl above the ghostly landscape. Skeletal branches of ash and oak trees are bedecked with black birds. Atangled mat of wild geranium covers much of the island. “Maybe it’s not pretty,” says Irene Mazzocchi, a DEC wildlife technician, “but you have to admit it has a certain magnificence.”

Four steps in from the mussel-shelled beach, we’re deafened by the high-pitched shrieks of thousands of ring-billed gulls as they swirl in a blizzard around our heads. We skirt a colony of some 1,500 pairs of Caspian terns (the only such colony in New YorkState) and trek through 50,000 pairs of ring-bills.

“I love cormorants,” says Chip Weseloh. “But great egrets and black-crowned night herons and other species are being turfed off by them, and vegetation on LakeOntario islands is being wiped out. We do need to restrict the cormorants to certain islands and push them off the others.”

The cormorant nests are clustered on the ground on the outer fringes of the island. As we approach, the birds get up and move away, exposing clutches of pale, aqua-colored eggs. The nests are woven from thick, longish twigs, and they incorporate slips of plastic, string, old lures, dead herring gull carcasses, even a pair of battered sunglasses.

Wielding a sprayer wand and working fast, Russ McCullough coats each egg with corn oil, moving from nest to nest and calling out the number of eggs in each to Mazzocchi, who writes it down. As soon as we move on, the birds hurry back to their nests, unaware that no chicks will hatch from these eggs.

Even the oiling of cormorant eggs is a subject of intense debate. Though most Henderson fishermen are all for it, some of them say that the repeated visits to Little Galloo are disturbing the birds and worsening the problem by causing them to move to new areas. Indeed, up and down the Great Lakes and into the St. Lawrence River, cormorants are nesting in places they haven’t been seen in before. Several researchers, including DEC biologist Jim Farquhar, believe that shooting adults off nests without chicks may be more humane and effective than oiling eggs. Some DEC biologists also advocate developing a coordinated international effort to control cormorant populations. And Congressman John McHugh (R-NY) has introduced legislation to open a hunting season on cormorants.

before leaving henderson, I stop by the Ditch marina. Ora is minding the gas pump while her husband busies himself upstairs. “Ron thinks it’s all the cormorants’ fault because that’s what he sees,” she says. “It’s not just that, of course. It’s the cost of gasoline. It’s that Canadians don’t come here anymore because of the exchange rate. It’s that people aren’t coming because of publicity about the cormorants.

“And do you know what?” she asks. “Young folks just aren’t fishing anymore. They don’t have time to fish! Soccer practice, piano lessons, play practice. My own grandchildren don’t have time to fish. Heck, no one even eats together anymore.” She shakes her head and echoes her husband’s words. “This place will never go back to being what it was.”