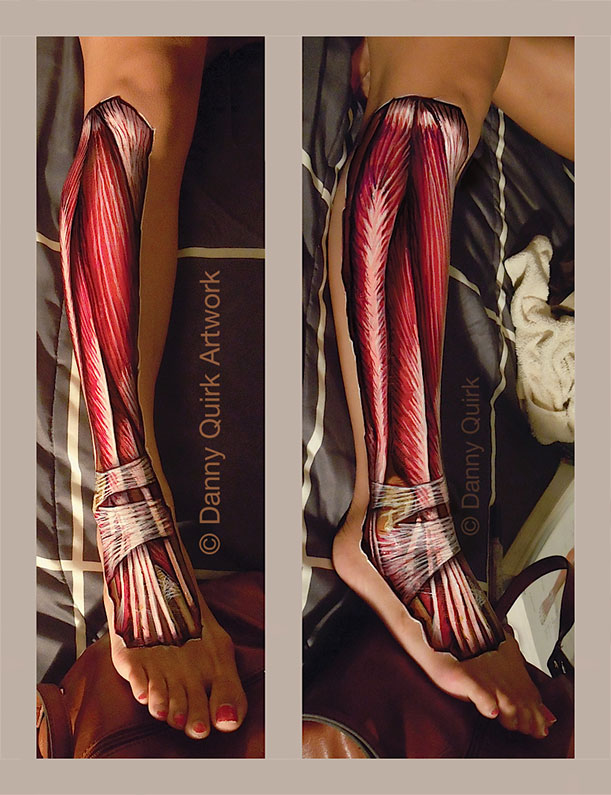

Should We Use Body Painting to Teach Anatomy?

Artist Danny Quirk’s paintings on the skin of willing friends show in textbook-like detail the muscle, bone and tissue that lie underneath

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Collage-painting-anatomy.jpg)

There are tribal tattoos, photorealistic tattoos, celtic tattoos and biomechanical tattoos. Then, there is a whole genre called anatomical tattoos. Chris Nuñez, a tattoo artist and judge on Spike’s TV show Ink Master, has said that this style is all about “replicating a direct organ, body part, muscle, tissue, flesh, bone in the most precise way you can.”

Danny Quirk, an artist working in Massachusetts, is doing something similar, only his anatomical tattoos are temporary. He creates body paintings with latex, markers and some acrylic that appear as if his models’ skin is peeled back.

The project began in 2012, when Halloween provided the occasion for Quirk to paint his roommate’s face and neck. From there, he made other anatomical paintings on the arms, backs and legs of willing friends, and his photographs went viral.

“The paintings started off very rough around the edges, having a ripped skin aesthetic,” says Quirk, “but as they grew, I started making them more anatomical, showing the adipose around the cuts and proper layering of nerves and vessels. I really started making medical illustrations in a new and different way than what was done before. I made ‘living lectures’ for lack of a better term.”

Quirk has his sights set on a career in biomedical illustration. He graduated from the Pratt Institute in New York in 2010, with a bachelor of fine arts in illustration, and then applied to medical schools. Without having some of the necessary science prerequisites, he wasn’t admitted, so he got a little creative. Kathy Dooley, a professor at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, asked Quirk to do 10 to 15 illustrations for her class, and he did a little bartering, trading the artwork for a spot in her doctorate-level gross anatomy course. It was in this class that the artist got to dissect a cadaver.

“Let’s just say, the books are much prettier than the real thing. In the books, everything is color coded and pretty, where as in the labs, everything was grey, with the exception of tendons, which have a beautiful, silvery iridescent shine to them,” he says. “I learned first hand that despite its drab hue, the body is a fabulously constructed machine. It’s like lace that can stop bullets—the intricacy of its inner workings are so fine and delicate, and yet the strength and durability behind each structure is unreal.”

Quirk likes to say that he now dissects with his paintbrush. To some extent, the subject of a painting is determined by the model, and his or her features, he explains. If he has a volunteer with a particularly muscular neck, he’ll add his flourishes there.

“When you find bony landmarks, it’s just a matter of hooking the right muscles up to the right places on the bones, and coloring it in from there,” says Quirk. Of course, the time he spends on any anatomical painting depends on its size and complexity. A full rendering of a model’s back, with not just superficial musculature but also the deep intrinsics, can take up to 14 hours to complete, though the average illustration demands about four to six hours.

One of the advantages of Quirk’s anatomical body paintings is that they dynamic, compared to other biomedical illustrations, which are static images. ”I paint my anatomy very precisely, making sure to match up origins and insertions, so that when the model moves, the painting moves with it, really illustrating what happens under the skin,” he says.

Quirk is trying to arrange some guest speaking gigs at schools, where he’d use his body painting to teach anatomy. He is also working on a timelapse video of a painting in progress, overlaid with educational notes.

“Aside from that, I really want to find a bald head,” he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)