Sinking a Sauropod

Paleontologists are naming new dinosaurs every week, but some names are eventually sent to the scientific wastebasket

![]()

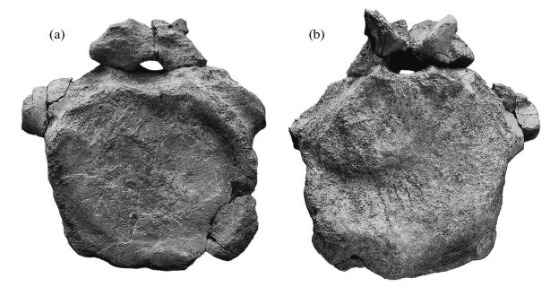

One of the vertebrae–as seen from the front (a) and back (b)–used to name the dinosaur Arkharavia heterocoelica. Although originally thought to come from a sauropod, it turns out that this bone belonged to a hadrosaur. From Alifanov and Bolotsky, 2010.

Dinosaurs come and go. Even though paleontologists are naming new dinosaurs at a fantastic rate–hardly a week seems to go by without the announcement of a previously-unknown species–researchers are also sinking and revising previously-discovered taxa as new finds are compared against what has already been found. The ever-growing ontogeny debate–which threatens the horned dinosaur Torosaurus and the hadrosaur Anatotitan, among others–is just one part of these paleontological growing pains. Sometimes dinosaur identity crises can be even more drastic.

Yesterday I wrote about a new paper by paleontologist Pascal Godefroit of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences and co-authors that redescribes the charismatic hadrosaur Olorotitan. As I read through the paper, a brief, but significant, side note caught my eye. In the section describing the deposits in which the known Olorotitan skeletons were found, the paper mentions that paleontologists V.R. Alifanov and Yuri Bolotsky described a sauropod–one of the long-necked, heavy bodied dinosaurs–from the same locality. On the basis of a tooth and several isolated tail vertebrae, Alifanov and Bolotsky named the dinosaur Arkharavia in their 2010 description. Since the encasing rock was deposited during the latest Cretaceous, around 70 million years ago or so, this was apparently one of the last sauropods on earth.

Only Godefroit and colleagues, including Yuri Bolotsky, have now revised the identity of Arkharavia. In their paper on Olorotitan, the paleontologists make the passing comment that “those vertebrae likely belong to hadrosaurid dinosaurs.” Rather than being a previously-unknown kind of sauropod, then, the fossils used to name “Arkharavia” probably belonged to one of the two hadrosaurs that dominate the locality–Olorotitan or Kundurosaurus.

This isn’t the first time a hadrosaur has been confused for a sauropod. Two years ago, paleontologists Michael D’Emic and Jeffrey Wilson of the University of Michigan and Richard Thompson of the University of Arizona determined that so-called “sauropod” vertebrae found in the 75-million-year-old rock of Arizona’s Santa Rita Mountains should actually be attributed to a hadrosaur akin to Gryposaurus. Fragmentary dinosaurs can be extremely tricky to identify correctly.

These changes aren’t frivolous. Identifications of isolated bones affect our understanding of dinosaur evolution and history. In the case of the misidentified hadrosaur bones from Arizona, the revised diagnosis altered the picture of when sauropods returned to North America after an absence spanning tens of millions of years. (This is called the “sauropod hiatus” by specialists.)

In the case of Arkharavia, the fossils represented one of the last dinosaurs in eastern Russia before the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. Misunderstood as sauropod bones, the fossils appeared to be the scrappy evidence for an entire group of dinosaurs at the locality. Properly understood as hadrosaur tail bones, though, the fossils become isolated elements from a group already known to be numerous in the fossil beds. While these changes might sound small, they can certainly influence grand-scale analyses of when certain groups of dinosaurs appeared or went extinct. There’s a big difference between sauropods living alongside hadrosaurs just before the end-Cretaceous mass extinction and a habitat dominated by hadrosaurs and devoid of sauropods. Even isolated bones can make a big difference.

References:

Alifanov, V., Bolotsky, Y. (2010). Arkharavia heterocoelica gen. et sp. nov., a New Sauropod Dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of the Far East of Russia Paleontological Journal, 44 (1), 84-91 DOI: 10.1134/S0031030110010119

Godefroit, P., Bolotsky, Y.L., and Bolotsky, I.Y. (2012). Olorotitan arharensis, a hollow-crested hadrosaurid dinosaur from the latest Cretaceous of Far Eastern Russia. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica DOI: 10.4202/app.2011.0051

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)