Smithsonian Researchers Are Bringing the Oryx Back to the Wild

Reintroducing the species back to north-central Africa shows early signs of success

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/89/42/8942e220-1179-4177-b286-d6a0c19d144e/apr2017_h03_phenom.jpg)

Last September, researchers at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, Virginia, were sitting at their computers poring over data that had been delivered via satellite from a game reserve in Chad, 6,000 miles away. The data—location coordinates and time stamps—had been collected on GPS collars worn by the most closely monitored herd of oryx on the planet. Over the last few days, a female had separated from that herd. Where was she?

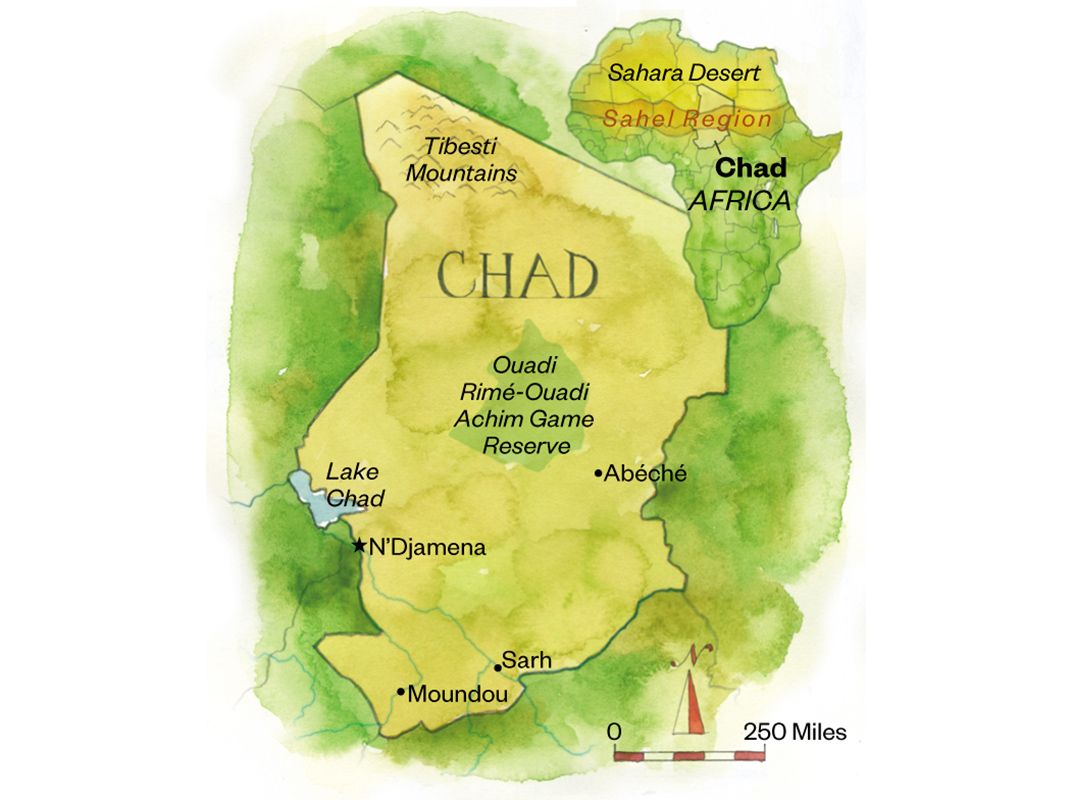

The researchers emailed her last known coordinates to colleagues at Chad’s Ouadi Rimé-Ouadi Achim Faunal Reserve. With that information, plus radio-telemetry antennas to detect signals from her collar, they headed into the wild—and found her with a newborn calf.

“That was a pretty big occasion for the team,” says Jared Stabach, one of the researchers at the institute. It was a pretty big deal for the animals, too—the first wild birth of a scimitar-horned oryx in nearly 30 years, and a milestone in one of the world’s most ambitious attempts to reintroduce a large-animal species that had been obliterated in the wild.

There was a time when as many as a million of this species of oryx—an antelope named for its magnificent curved horns—roamed the Sahel, the semiarid belt that stretches across western and north-central Africa. “There’s a whole assemblage of species that evolved to thrive in the desert,” says Steve Monfort, director of the Conservation Biology Institute and president of the Sahara Conservation Fund, two of eight international partners in the reintroduction effort. “The oryx are the largest and most symbolic of all of that.”

But parts of their habitat fell to agriculture or development, poachers went after the animals’ coats and horns, and in Chad, combatants in the country’s post-independence civil war in the 1960s hunted them for meat. The last confirmed sighting of an oryx in the wild was in 1988, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Before the wild oryx disappeared, however, conservationists rescued scores of them to start captive herds. Today, the largest, about 3,000 strong, is controlled by the Environment Agency—Abu Dhabi, the lead partner in the restoration project. Last summer, 25 animals from that herd were airlifted to Chad and released at Ouadi Rimé-Ouadi Achim. The goal is to release a total of 500 animals over the next five years.

Rather than collaring just a few members of the herd with GPS devices, Monfort has arranged for each animal to wear one while on the reserve, which covers more than 30,000 square miles. “If you don’t know how an animal moves or where it goes or what its needs are during its life cycle, you can’t design a program that will help it to survive,” Monfort says.

While it’s too early to draw any grand conclusions, the calf’s birth last September hasn’t been the only hopeful sign. Some of the other females who were released then are showing signs of being pregnant now.

“A birth is a milestone because it shows they are acclimating,” says Stabach. “Eventually they will be able to sustain themselves without human intervention.”

Related Reads

Animal Reintroductions: The Arabian Oryx in Oman

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)