Learn to Speak the Language of the Universe With This Mindblowing New Book

Magnitude helps you imagine the outer limits of time, speed and distance—without breaking your brain

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/25/16/2516a14a-6d28-4bca-b31b-a75bdef2c3db/screen_shot_2017-12-27_at_111046_am.png)

When you spend all your time talking about the universe, there are a few questions you end up getting a lot. Namely: How big? How far? How old? How fast?

Kimberly Arcand and Megan Watzke, both science communicators for NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, get those questions all the time—at talks, events, or via email and social media. So last year, they decided to answer them in the most engaging way possible. In a visually stunning book called Magnitude: The Scale of the Universe they explore the full range of scales we’ve measured in our Universe in four main sections covering: Quantities, Rates and Ratios, Phenomena and Process, and Computation.

Their project harkens back to Powers of Ten, the 1977 short film that illustrated the scale of the universe by starting from a picnic on a Chicago lakeside, and periodically expanding the frame by a factor of ten.

“Eames Demetrios, the grandson of Charles and Ray Eames who made the original 'Powers of Ten' film, argues that understanding scale is a form of literacy. And I think he’s absolutely right,” Watzke tells Smithsonian.com. “If you want to become literate in a foreign language, you can start with some common phrases. From there you can add more words, grammar, etc. Over time you can build fluency. We hope that people can use Magnitude as a starting point to learn how to ‘speak’ scale and gain a deeper understanding and comfort level with it over time.”

The illustrations in the book are by Katie Peek, a former astrophysicist who later transitioned to data visualization and science journalism. “The look was an iterative process,” Peek says. “The core of the book—Megan and Kim's idea—was to move from the very small to the very big in about ten steps for each chapter. One of my favorite innovations in the layout came from [the design company] Alexander Isley. They created a lovely progression of illustration sizes in each chapter, so the small values begin with a narrow picture, and the large values have a much bigger picture. It's a subtle nod to what Kim and Megan set out to achieve.”

Magnitude is a journey across time and space, the familiar and the unfamiliar. Best of all, it’s meant for curious people of all ages and interests and expertise levels, not just scientists. “It’s something you can pick up for just a few minutes and get a glimpse of a topic, or do a deeper dive into the book at a longer stretch,” says Arcand. Get a taste for yourself by exploring selected pages from the book. Explanations and units are below; click the page for a larger view.

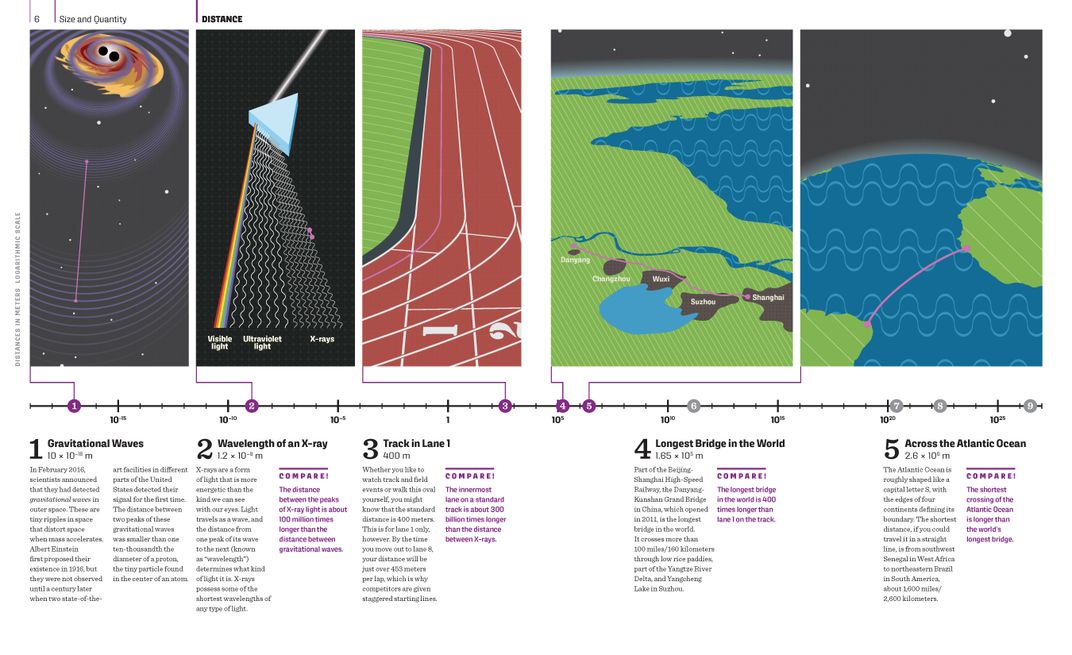

Distance: Measured in meters (m).

The range of distances humans have measured spans 40 orders of magnitude. Starting with the wavelength of the first gravitational wave signal detected by LIGO in February 2016 (10 x 10^18m) and ending with the distance to the farthest galaxy ever detected (1.25 x 10^26m). [That distance record was broken by the Hubble Space Telescope in March 2017, after the book went to print].

The longest bridge in the world is located in China and spans 160 kilometers. You would need 400 Danyang-Kunshan Grand Bridges end-to-end to cross the Atlantic ocean at its narrowest point from southwest Senegal in West Africa to northeastern Brazil in North America.

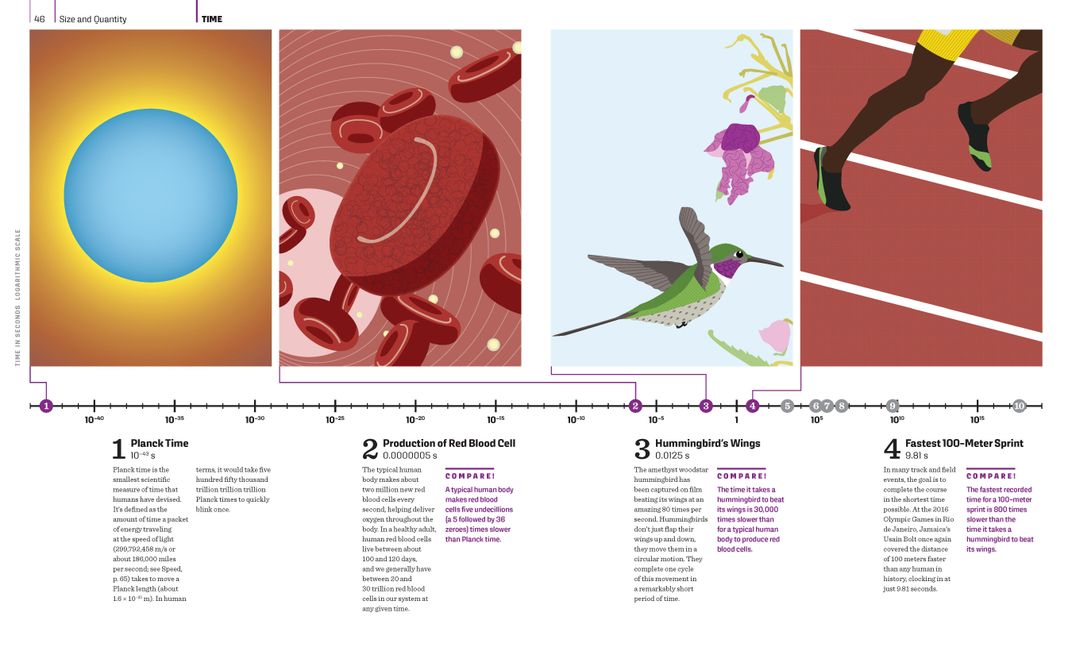

Time: Measured in seconds (s)

We’ve measured time over more than 55 orders of magnitude. Did you know that in the time it takes a hummingbird to beat its wings once, your body can produce 25,000 red blood cells? Furthermore, during the 2016 Olympic games, Usain Bolt’s set a new world record for the 100-m race, completing it in 9.81 s. In that same amount of time, the same hummingbird would have beaten its wings almost 800 times.

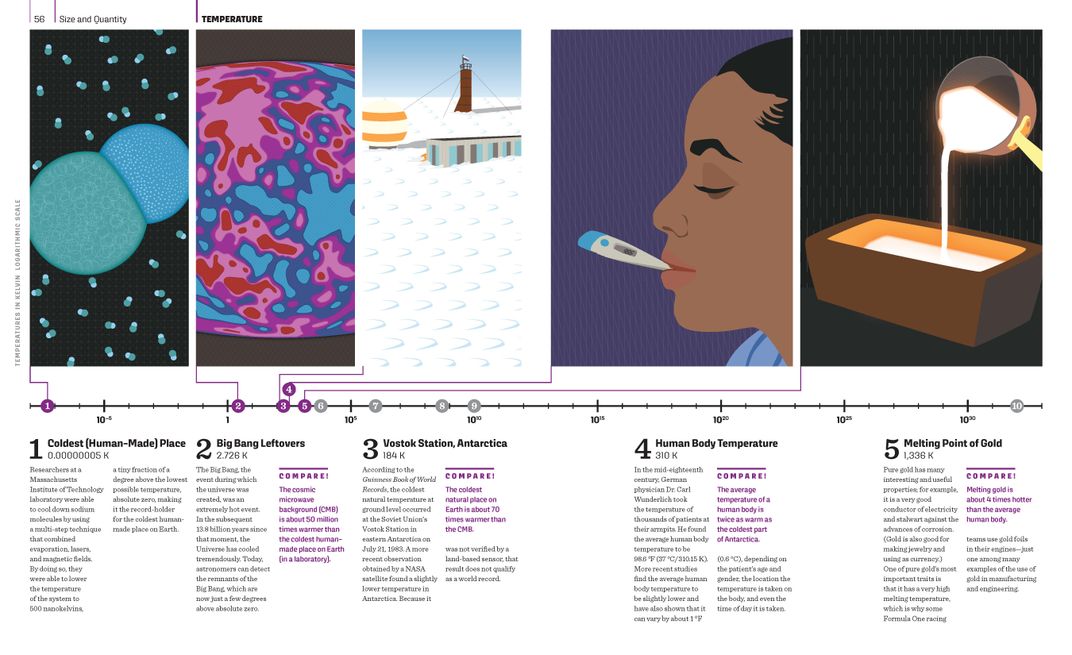

Temperature: Measured in degrees Kelvin (K).

The coldest human-made) temperature we’ve ever recorded on Earth was in a laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where researchers cooled sodium molecules to 0.00000005 K (or 500 nanokelvins). The coldest natural temperature recorded (at ground-level) was 184 K, as measured at Vostok Station in easter Antarctica in July 1983. Vostok is also the source of the ice cores that provide historical temperature and CO2 records on Earth for the past 400,000 years. As you read this, your average body temperature is twice as warm as the temperature recorded at Vostok Station.

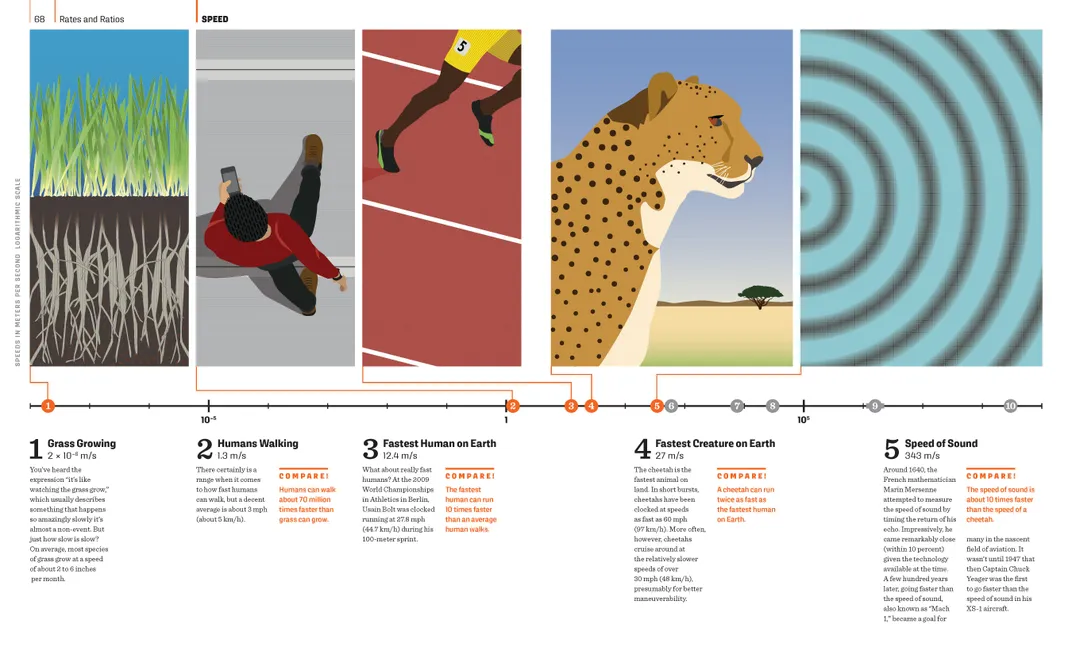

Speed: Measured in meters per second (m/s).

Ever heard the phrase "slow as watching the grass grow”? Arcand and Watzke have quantified that for you. It turns out that grass grows at 2 x 10^-8 m/s, or 2 to 6 inches per month, which somehow seems faster than it should. Returning to Usain Bolt, his fastest speed ever recorded was 12.4 m/s in the 100-m sprint at the 2009 World Championships in Berlin, Germany. Unfortunately for Bolt, the fastest animal on Earth, the cheetah, can run the same event in less than half the time at a top speed of 27 m/s. Interspecies Olympics anyone?

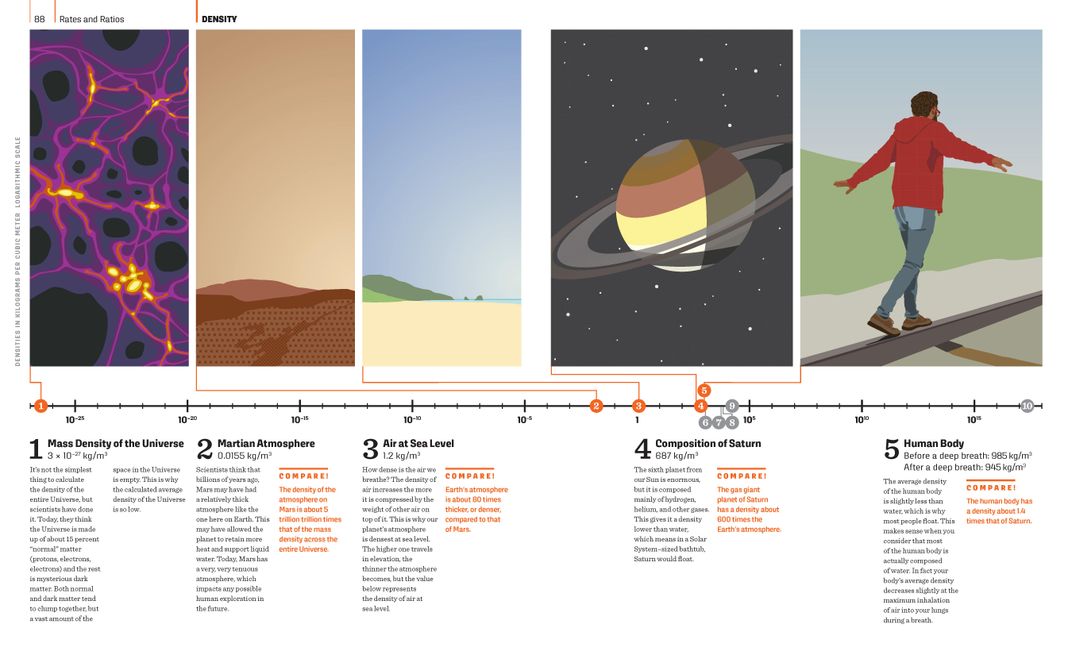

Density: Measured in kilograms per cubic meter (kg/m^3).

The more mass you can pack into a given space, the higher the resulting density. While space is often described as a vacuum, it’s not completely void of mass. If you average out all the mass both condensed into stars, planets, rocks and dust with the vast amount of space between them, you get an average of 3 x 10^-27 kg/m^3. That’s roughly less than one atom per cubic centimeter. Looking at planets in our own Solar System, at 687 kg/m^3, Saturn is less dense than water so it would theoretically float in an astronomically large bathtub. Humans are 1.4 time denser than Saturn at an average of 965 kg/m^3, but we float in bathtubs, rivers, lakes and oceans too because (fresh) water has density of 1000 kg/m^3. Now I really want to take a bath with in space.

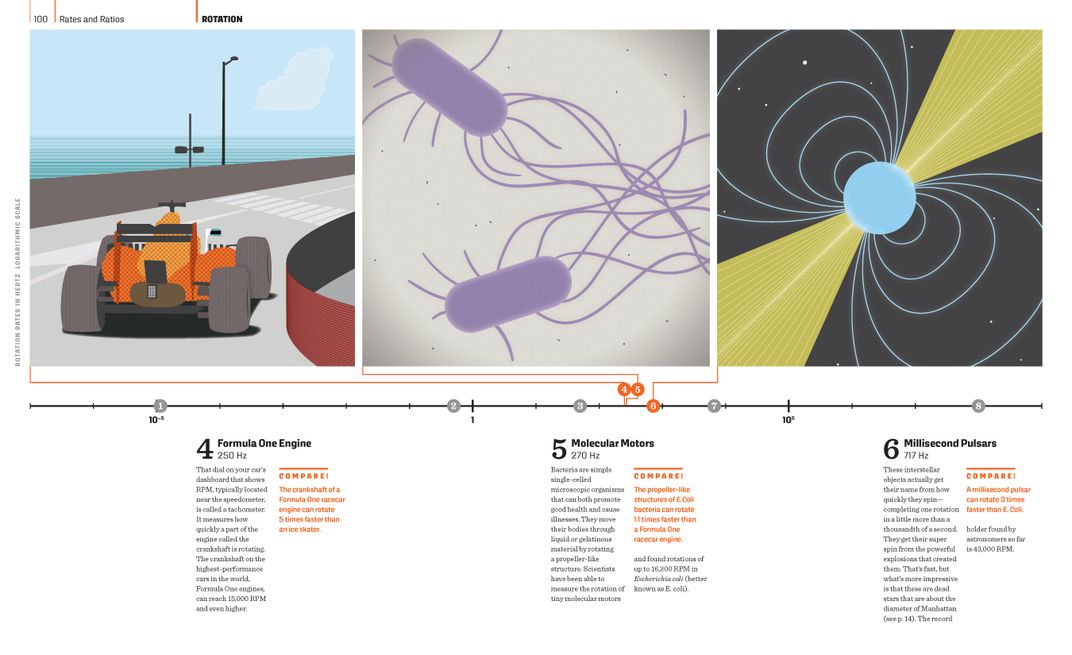

Rotation: Measure in Hertz (Hz), aka rotations per second (1/s).

Rotational speed tells how long it takes a given object to turn once on its axis. We are most familiar with Earth’s rotational speed, roughly once every 24 hours, which translates to 0.0000115 Hz or 1000 times slower than a vinyl record. The highest performance cars in the world (Formula One) have engines that run up to 250 Hz, that’s 15,000 RPM. But even faster than that are the tiny molecular motors that propel E. Coli bacteria around your large intestine, which rotate at 270 Hz. If you hold really still, maybe you can feel them racing around in there.

Magnitude: The Scale of the Universe

In Magnitude, Kimberly Arcand and Megan Watzke take us on an expansive journey to the limits of size, mass, distance, time, temperature in our universe.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.