Swamp Wallabies Can Get Pregnant While Pregnant

These marsupials can conceive during the final days of an ongoing pregnancy, creating a “backup” embryo ready to take its predecessor’s place

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3f/86/3f86b292-c25b-4ee5-97e8-fd6433dc185c/swamp-wallaby-4366382.jpg)

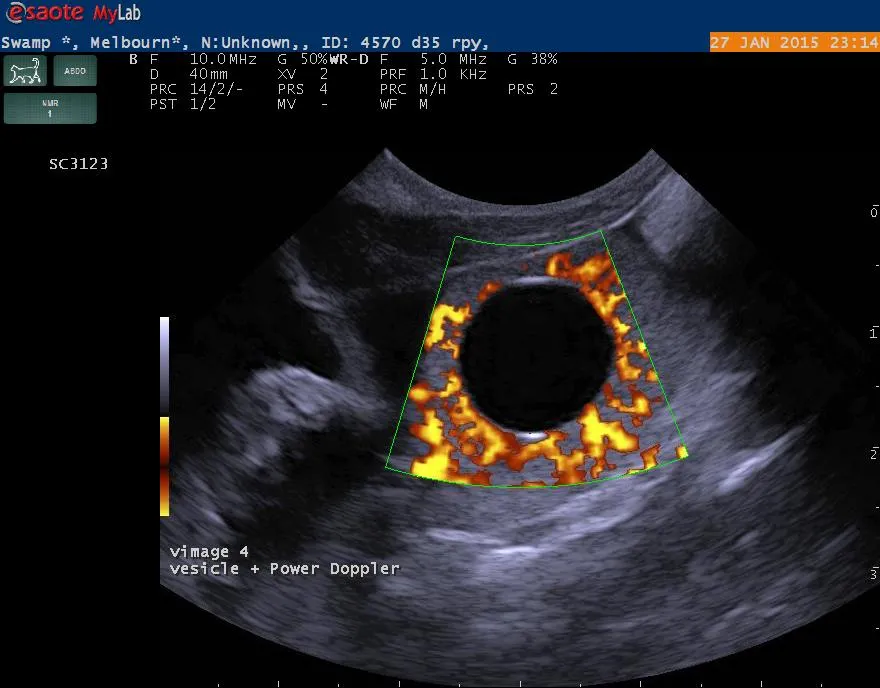

That day in 2015 was one Brandon Menzies would never forget. Squinting at the sonogram before him, he fixed his eyes on a teeny, discolored speck. At just a millimeter in length, the smear was barely perceptible.

But Menzies, a biologist at the University of Melbourne, knew what he saw: a 12-day-old swamp wallaby embryo, not two weeks away from being born. The fetus was evidence that the female marsupial in his care had, in the midst of an ongoing pregnancy, conceived a second time.

“I was so excited,” Menzies says. “It validated everything.”

His team’s findings, published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, lend credence to a decades-old hypothesis that female swamp wallabies (Wallabia bicolor) can start a second pregnancy before finishing their first. By alternating embryo implantations between two reproductive tracts—each with its own uterus and cervix—these marsupials can gestate nonstop throughout their entire adulthoods, staying knocked up for up to seven years straight, Menzies estimates.

“As soon as they reach sexual maturity, these females are—perhaps unfortunately—pregnant all the time,” Menzies says. Tacking on the months-long stints of suckling once offspring are born, female swamp wallabies may end up supporting three young at once: an older joey that’s left the pouch, a young one nursing inside of it and a fetus that has yet to be born.

Conceiving during pregnancy sounds on its surface like “a peculiar mode of reproduction,” says Ava Mainieri, an evolutionary biologist at Harvard University who wasn’t involved in the study. But the strategy seems to work for the wallabies, who should perhaps be admired for their resilience. “The female reproductive body is amazing,” she adds. “Any strategy a [female body] can capitalize on … to increase her fitness, she will use.”

Scientists have puzzled over swamp wallabies’ unusual reproductive tactics since at least the 1960s, when a trio of researchers noticed three females engaging in sex very late into their pregnancies—an act that, under typical circumstances, has no reproductive benefit. But without an easy, minimally invasive way to study the marsupials’ reproductive tracts, investigating the impetus behind these oddly timed trysts was all but impossible.

Half a century later, Menzies and his colleagues used modern imaging technology to tackle the mystery. In 2015, they captured a small troupe of wild wallabies and monitored them through several pregnancies via a portable ultrasound machine.

Performing sonograms on swamp wallabies isn’t easy, especially with their pouches in the way, says study author Thomas Hildebrandt, a mammalian reproduction expert at the University of Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research. Fortunately, wallaby embryos progress through development on a predictable trajectory, enabling researchers to calculate their age, almost to the day, based on size alone.

During the study, two female wallabies lost their fetuses late in pregnancy, possibly through spontaneous miscarriages. Ten days later, the scientists discovered that both animals were harboring embryos that looked almost two weeks old, suggesting that they’d been conceived while the older fetuses were still gestating. In keeping with this, the wallabies seemed to have their timing down pat: Vaginal swabs revealed that the animals had sex only when females were close to giving birth.

That swamp wallabies get pregnant while pregnant “has been suspected for a long time,” says Diana Fisher, an ecologist and conservationist at the University of Queensland, who wasn’t involved in the study. But, she says, the team’s findings constitute the first “very clear demonstration that this is what they’re actually doing.”

Only one other mammal is known to exhibit this behavior: the European brown hare (Lepus europeaus), which can conceive about four days before delivering a litter. By shortening the time between births, mother hares can boost the number of offspring they produce in a given breeding season, sometimes by more than 35 percent. (European brown hares, however, mate only at certain times of the year and can’t be pregnant in perpetuity.)

The same can’t be said for swamp wallabies. Although their gestation period lasts just a few weeks, female swamp wallabies give birth only about once a year, then spend the next 11 months nursing their fragile newborns in the pouch. During that time, any new embryo that’s already been conceived will enter a state of dormancy, waiting until its older sibling is weaned before resuming growth.

This reproductive hiatus exists to minimize the energetic demands on the mom so she can focus on churning out lots of nutrient-rich milk. It also negates what might seem the most obvious perk to be gained from mid-pregnancy mating: giving birth to a second offspring soon after the first and maximizing the total number of joeys. With this pause button in place, swamp wallabies would, in theory, end up with the same number of joeys even if they waited a few extra days, weeks or months after giving birth to have sex again.

Still, Menzies has his own suspicions for the marsupials’ odd behavior. Perhaps the limiting factor in their lifestyle isn’t the length of gestation, but the availability of mates. Unlike many other marsupials, which hang out in groups called mobs, swamp wallabies are solitary, meeting up only infrequently for the occasional reproductive rendezvous.

“If there are no other animals around, perhaps it needs a longer period of [being receptive] to mating,” Menzies says. In some cases, those few extra days could be a female wallaby’s only chance to couple up.

Overlapping pregnancies could also act as a childbearing insurance policy, says Elisa Zhang, a reproductive biologist at Stanford University who wasn’t involved in the study. If a newborn joey dies, the mother has a backup waiting to take its place.

Mainieri says sussing out the answers to these questions will take more research, including further comparisons between swamp wallabies and the European brown hare. But future findings could tell us a little bit about our own species, too: Some suspect that humans may also be capable of conceiving anew during pregnancy. (For these rare cases to arise, an egg must release accidentally during an ongoing pregnancy, be fertilized and then implant in the already-occupied uterus—all flukes our bodies have evolved to prevent.)

As Australia slowly recovers from its recent spate of devastating wildfires, these unusual wallabies and their reproductive quirks should serve as a reminder of the dazzling diversity the Earth stands to lose, Hildebrandt says. “Evolution has all kinds of surprises ready for us if we study it,” he says. “We should protect it—not destroy it before we have had the chance to understand it.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)