Swimming With Whale Sharks

Wildlife researchers and tourists are heading to a tiny Mexican village to learn about the mystery of the largest fish in the sea

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/whale-sharks-631.jpg)

At the moment, Rafael de la Parra has but one goal: to jump into water churning with whale sharks and, if he can get within a few feet of one, use a tool that looks rather like a spear to attach a plastic, numbered identification tag beside the animal’s dorsal fin. De la Parra is the research coordinator of Proyecto Dominó, a Mexican conservation group that works to protect whale sharks, nicknamed “dominoes” for the spots on their backs.

He slips off the fishing boat and into the water. I hurry in after him and watch him release a taut elastic band on the spear-like pole, which fires the tag into the shark’s body. De la Parra pops to the surface. “Macho!” he shouts, having seen the claspers that show it’s a male.

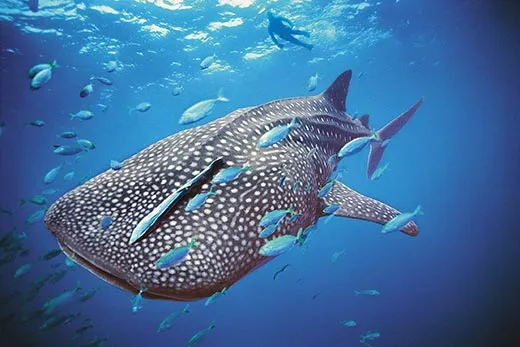

The biggest fish in the sea, a whale shark can weigh many tons and grow to more than 45 feet in length. It’s named not only for its great size but its diet; like some whale species, the whale shark feeds on plankton. A filtering apparatus in its mouth allows it to capture tiny marine life from the vast amount of water it swallows. But it is a shark—a kind of fish with cartilage rather than bone for a skeleton—a slow-moving, polka-dotted, deep-diving shark.

De la Parra and a group of American scientists set out this morning from Isla Holbox off the Yucatán Peninsula. The sleepy tourist island, whose primary vehicles are golf carts, has become a research center where scientists study whale sharks. The animals spend most of their lives in deep water, but they congregate seasonally here off the coast of the Yucatán, as well as off Australia, the Philippines, Madagascar and elsewhere. No one knows for sure how many whale sharks are in these waters, but the best estimate is 1,400. The global whale shark population may number in the hundreds of thousands.

Researchers have fastened IDs to about 750 whale sharks here since the scientists started studying them in earnest in 2003, and they hasten to say the procedure does not seem to hurt the animal. “They don’t even flinch,” says Robert Hueter, a shark biologist at the Sarasota, Florida-based Mote Marine Laboratory, which collaborates with Proyecto Dominó. The researchers have outfitted 42 sharks with satellite tags, devices that monitor water pressure, light and temperature for one to six months, automatically detach and float to the surface, then transmit stored information to a satellite; scientists use the data to recreate the shark’s movements. Another type of electronic tag tracks a shark by transmitting location and temperature data to a satellite every time the animal surfaces.

Despite all the new information, says Ray Davis, formerly of the Georgia Aquarium, “there are a lot of unanswered questions out there. Everyone’s admitting they don’t know the answers, and everybody’s working together to get the answers.”

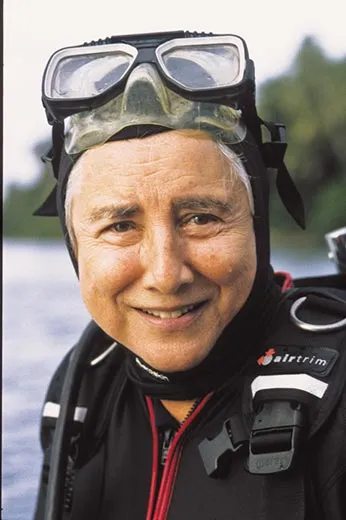

Eugenie Clark is Mote’s founding director and one of the pioneers of shark research. The first whale shark she observed, in 1973, was a dead one caught in a net in the Red Sea. Once she began studying live ones, in the 1980s, she was hooked. On one occasion, she grabbed the skin under a whale shark’s first dorsal fin as it cruised by. She held on, going ever deeper underwater until, at some point, it occurred to her she’d better let go.

“It was incredible,” Clark remembers. “When I finally came up, I could barely see the boat, I was so far away.”

Clark, who is 89 and continues to do research, recalls the ride with impish delight. At one point, as we sit in her Florida office, she casually mentions a recent dive, then catches herself. “Don’t mention how deep I went,” she whispers. “I’m not supposed to do that anymore.” Then she explodes in laughter.

As she studied feeding behavior in whale sharks, she noticed that juveniles, less than 35 feet long, fled from humans, but larger animals didn’t seem to mind nearby divers.

The fish have mostly been a mystery. Only in 1995 did scientists determine how whale sharks come into the world, after Taiwanese fishermen pulled up a dead female carrying 300 fetuses in various stages of development. These sharks are “aplacentally viviparous,” meaning the young develop inside eggs, hatch, then remain in the mother’s body until the pups are born. With the astonishing number of eggs, the whale shark became known as the most fecund shark in the ocean.

When two male whale sharks at the Georgia Aquarium died within several months of each other in 2007, scientists traveled to Atlanta to observe the necropsies. Analysis of the bodies helped researchers understand the 20 sieve-like pads the animals use for filter-feeding. Recent research by Hueter, De la Parra and others has shown that whale sharks primarily eat zooplankton in nutrient-rich coastal waters, like those near Isla Holbox; in other areas they seek out fish eggs, especially those of the little tunny. If they gulp something too big, they spit it out.

Rachel Graham, a conservation scientist at the Wildlife Conservation Society, was the first to attach a depth tag to one of the giants, in Belize in 2000. One of the 44 satellite tags she eventually deployed told her that a whale shark had dived 4,921 feet—nearly a mile. A marine biologist named Eric Hoffmayer recorded the deepest dive yet: in 2008, he monitored a shark in the Gulf of Mexico that descended 6,324 feet. “Their ability to adapt to all sorts of different environments is an important part of their survival,” says Graham, who’s tracking whale sharks in the Western Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico and Indian Ocean. Scientists don’t know why the animals go so deep. Sharks lack a swim bladder that keeps other fish buoyant, so one idea is that whale sharks free-fall toward the seafloor to rest.

In 2007, Hueter tagged a pregnant 25-foot-long female he nicknamed Rio Lady. Over the following 150 days, she traveled nearly 5,000 miles, from the Yucatán Peninsula through the Caribbean Sea to south of the Equator east of Brazil, ending up north of Ascension Island and south of St. Peter and St. Paul Rocks, roughly halfway between Brazil and Africa. No one is certain where whale sharks breed or give birth, but Hueter believes this area may be one of their elusive pupping grounds.

Legend has it that Isla Holbox, a former pirates’ hide-out, got its name from a deep lagoon on the southern part of the island: Holbox means “black hole” in Mayan. But fresh water bubbling up from a spring in another lagoon was the island’s real draw: the Maya viewed it as a fountain of youth, and Spanish ships stopped there to take on fresh water. Mangroves divide the island, which is less than two miles wide.

A tour guide describes islanders as “descendants of pirates, mestizos of several races, fishermen by trade.” Residents earned a living by trapping lobster until about 2000, when the excessively hunted crustacean grew scarce and fishermen wondered what to do next.

Willy Betancourt Sabatini was one of the first Holboxeños to realize that the massive sharks that congregated near the island to feed might be the answer. He and his sister, Norma, a local environmentalist who now serves as project director for the island’s Yum Balam Protected Area, along with researchers and local entrepreneurs, established rules for a new industry, shark tourism. Only two divers and one guide can be in the water with a single shark; flash photography and touching the sharks are forbidden. Islanders had learned from the lobster debacle that they needed to set limits. “They know if we don’t take care, all of us are going to lose,” Norma Betancourt Sabatini says.

“Conserve the whale shark,” says a sign on Isla Holbox. “It’s your best game.”

Shark tourism is growing. Graham, in a 2002 study of whale shark visitors to the small Belize town of Placencia, estimated revenues of $3.7 million over a six-week period. In the Philippines’ Donsol region, the number of whale shark tourists grew from 867 to 8,800 over five years. And a study found whale shark tourists spent $6.3 million in the area around Australia’s Ningaloo Marine Park in 2006.

“It’s simple and more predictable than fishing,” Willy Betancourt Sabatini says of shark watching. The 12 men who work for him as boat operators and guides earn twice as much as they did fishing, he adds. “We respect the rules. People understand it very well.”

It had taken an hour for De La Parra, Hueter and others on the tagging expedition to reach the sharks. The water was smooth and thick with reddish plankton. “There’s one of them!” a researcher cried out, pointing to a large, shiny dorsal fin. We motored closer, and I found myself gazing at the largest shark—about 23 feet—I had ever seen. Its skin was dark gray, glinting in the sunlight, with mottled white dots.

Suddenly it seemed as if whale sharks were everywhere, though we could see only a fraction of their massive bodies: their gently curved mouths, agape as they sucked in volumes of water, or the tips of their tails, flicking back and forth as they glided through the sea.

I donned a mask, snorkel and fins and prepared to jump in. Hueter had told me he thought the sharks’ cruising speed was one to two miles an hour—slow enough, I thought, to swim alongside one without much difficulty.

Wrong.

I made a rookie’s mistake and jumped in near the shark’s tail. I never caught up.

I tried again, this time hoping to swim out to an animal half a dozen yards away. It didn’t wait.

Finally, I managed to plunge into the water near an animal’s head and faced an enormous, blunt-nosed creature, coming toward me at what seemed like a shockingly rapid rate. While I marveled at its massive nostrils and eyes on either side of its head, I realized I was about to be run over by a 3,000-pound behemoth. Never mind that it doesn’t have sharp teeth. I ducked.

It cruised by, unperturbed. By the time I climbed back into the boat, everyone was ready with quips about how I had had to scramble to get away. I didn’t care. I had seen a whale shark.

Adapted from Demon Fish: Travels Through the Hidden World of Sharks by Juliet Eilperin. Copyright © 2011. With the permission of Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

Juliet Eilperin is the national environmental reporter for the Washington Post. Brian Skerry, a specialist in underwater photography, is based in Uxbridge, Massachusetts.