A Tale of Two Killer Whales

Orca whales actually comprise two distinct types—and one may soon be destined to rise above the other

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1f/7b/1f7b1003-0381-45f4-9d41-116f526ff546/kdb859-wr.jpg)

Bob Wright had a problem on his hands: five killer whales on a hunger strike.

Wright, the owner of Sealand of the Pacific in Victoria, British Columbia, had assembled a team to hunt killer whales. He was determined to find a mate for one of his captive whales, Haida. It was 1970, the heyday of live killer whale captures in the northeast Pacific, before strong regulations and public outcry stopped the practice. Wright’s team was out near Race Rocks in the Juan de Fuca Strait on a windy winter day when they spotted a rare white whale swimming with four companions. They followed.

Just as the sun was going down, the five whales swam through the entrance of Pedder Bay. The team quickly fixed a ratty gill net across the narrow entrance. To keep the hefty marine mammals away from the flimsy net, the men spent the night banging the hulls of aluminum skiffs with paddles and clubs. Periodically they dropped exploding “seal bombs”.

The next day, two fishing boats arrived with nets to better secure the entrance, and Wright prepared to move two females to Sealand and find buyers for the others.

For the once-free-roaming whales, a heartbreaking drama unfolded. Confined to the bay, they circled repeatedly, occasionally blundering into the net. And they refused to eat, despite offers of herring, salmon, and ling cod by their captors.

The white whale, Chimo, and another female, Nootka, endured Pedder Bay for 24 days until they were moved to Sealand to become Haida’s companions. The three other whales, one male and two females, remained at Pedder Bay and continued their fasts.

After 60 days of imprisonment, the three whales were so emaciated the contours of their ribs were starting to show. On day 75, one of the females charged the net, got stuck, and drowned. Her body was towed out to sea.

A few days later, the Pedder Bay male was offered yet another fresh salmon and finally bit. But instead of eating it, he started vocalizing and delivered it to the surviving female. She grabbed it by the tail, leaving the head hanging out the side of her mouth. The male came up beside her, grabbed hold of the head and the two circled the bay, before they each ate half. It was an astonishing scene, and it seemed to break the spell—for the next four and a half months, the whales ate the herring and salmon they were fed, until their captivity ended. One night, activists used weights to sink the nets, allowing them to escape, reflecting growing public discontent with such captures.

Months before, it had taken another act of cetacean altruism to break the fasts of Chimo and Nootka.

When they arrived at Sealand, the females were kept apart from Haida by a net that divided their tank. Haida ignored Nootka at first, then retrieved a herring and pushed it through the net mesh. He did the same for Chimo. For the first time in months, the females began to feed and eventually ate the fish offered to them by the aquarium staff.

It took another whale to finally encourage Nootka and Chimo to feed, but remarkably, it was likely the first fish either of them had ever eaten. Unbeknownst to Wright and his team, and the whale biologists and trainers of the day, there are different types of killer whales, with distinctive behaviors, extending even to the food they eat.

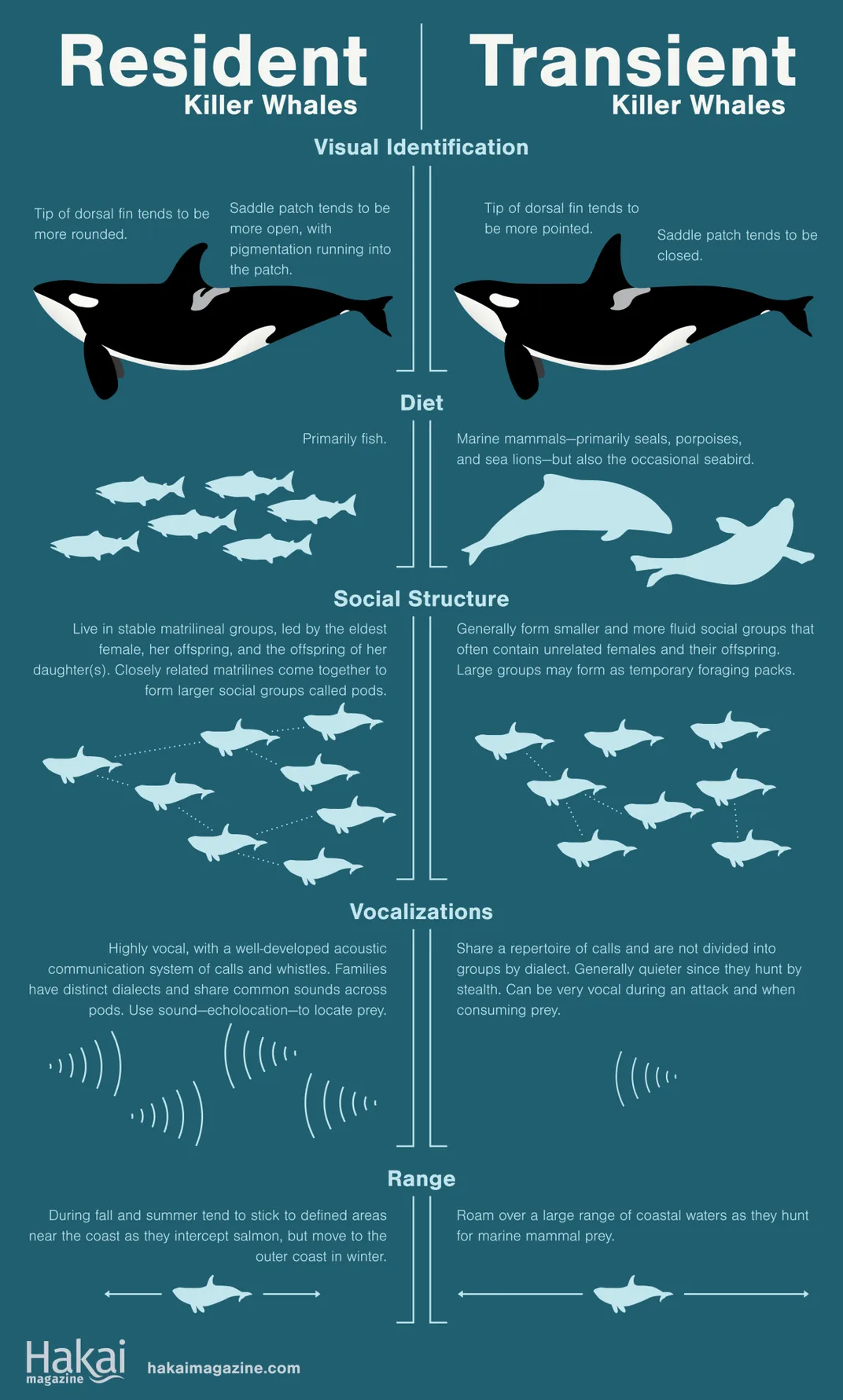

That winter day almost 50 years ago, Wright had captured a group of transient killer whales, a distinct ecotype of Orcinus orca that eats seals, sea lions, and other marine mammals, and one markedly different in many ways from the resident killer whale ecotype—including Haida—which feeds almost solely on salmon.

Graeme Ellis, a recently retired Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) research technician who worked with Wright at Sealand at the time, is still astounded by the cross-cultural sharing of food he witnessed between Haida, Chimo, and Nootka. “To share food across ecotypes, I still don’t know what to make of it,” he says.

In the wild, transient and resident killer whales do not share food. They rarely share space either, preferring to keep their distance. Today, this partitioning of the ocean and its food has affected the different populations unevenly. In the Salish Sea, home to an endangered population of killer whales called the southern residents, depleted stocks of chinook salmon—their preferred prey—are considered the main reason why the population has declined to a precarious 76. But transient killer whale populations in the same region have been increasing at an estimated rate of three percent annually since federal marine mammal protection in the United States and Canada in the early 1970s. The inshore population is now thought to number close to 300 from Washington to southeastern Alaska.

Adding to that population are the descendants of the two whales that escaped the net at Pedder Bay. Once they had access to the marine mammals that sustained them, they thrived. The female gave birth to at least three calves and was last seen in 2009. The male lived until at least 1992.

With the dramatic rise of their prey—particularly harbor seals—to historical levels, transients are not starving. Besides their primary diet of marine mammals, they’re also known to eat squid and even unsuspecting seabirds. Necropsies of dead transients reveal a “chamber of horrors”—stomachs filled with whiskers, claws, and other undigested prey parts, reports John Ford, an emeritus DFO whale scientist and adjunct professor at the University of British Columbia.

For now, times are good. With a changing ocean, what does the future hold for transient killer whales, their fish-eating cousins, and the ocean habitat they call home?

On a drizzly morning in March, I board a 9.3-meter inflatable boat, mere minutes from Pedder Bay, where Wright caught the five transients. Almost half a century later, people now hunt the whales for the sheer pleasure of seeing them in the wild, unconfined by the concrete walls of an aquarium.

Mark Malleson scans the rippled, slate-gray water for killer whales—a dorsal fin piercing the ocean surface, a ghostly breath from a blowhole, anything that looks out of the ordinary. The whale watching guide is optimistic based on observations of resident killer whales he made earlier that morning from a lookout station near Victoria. “We’ve got a few in the area,” he insists, peering through yellow-tinted sunglasses. “They’re really spread out.”

He powers up twin 200-horsepower engines and aims the inflatable at faint splashing about halfway between Victoria and Port Angeles, Washington, on the fluid international boundary of the Juan de Fuca Strait.

Malleson’s internal radar is on alert as he slows near a whale’s last imprint on the water. He stops and waits. Then an adult male bursts from the depths, using a powerful tail thrust to attack what Malleson suspects is a big chinook. “We call them chinookaholics, they’re so focused on that type of salmon.”

We scoot back and forth, chasing fins and sprays for an hour. Malleson estimates 25 resident killer whales are scattered across the strait on this cool, overcast morning. Under normal circumstances, he would call it a good day and retreat to Victoria’s Inner Harbour. This morning though, he is not searching for residents, but for transient killer whales.

Malleson maneuvers the boat for a final pass alongside the 220-hectare Race Rocks Ecological Reserve, which is known for its rich diversity of marine life, much of it transient prey. Sea lions are an excellent bet on rocky haulouts next to the historical 1860s lighthouse, and sightings of sea otters and elephant seals are also possible.

Despite all the transient killer whale food, Malleson is dubious about our chances of spotting both killer whale ecotypes in such close proximity.

We both cast a glance at Humpback Rock, a dark geological blip on the surface that resembles the small dorsal fin of a humpback whale. Malleson does a double take, then erupts with jubilation. “Unbelievable. I hope you don’t mind being late.”

Ten transients are following the rocky shoreline—just 200 meters ahead of the resident male we’d been observing. In a lifetime on the water, including 21 years as a whale watching guide, Malleson has witnessed residents and transients pass close by each other only a handful of times. He is a local expert on transients and receives a stipend from DFO and Washington State’s Center for Whale Research to track and photograph them, mainly in the Juan de Fuca Strait, but sometimes as far as the Strait of Georgia and Tofino on the west coast of Vancouver Island. “If anyone was going to find them, it’s me. I don’t want to blow smoke up my ass, but it’s true.”

The killer whales we see this day off Victoria are among the most studied in the world due to their proximity to population centers and a thriving whale watching industry.

Resident whales make it easier for researchers to study them by typically returning to known salmon fishing areas, such as Haro Strait off San Juan Island, during the annual summer runs. Not so with transients. Like the ones we see cruising the shoreline, they are quiet, stealthy hunters that typically travel 75 to 150 kilometers of coastline per day—at speeds of up to 45 kilometers per hour during short hunting bursts—and can pop up wherever prey might be found.

Scientists estimate transients diverged from other killer whales to form their own ecotype some 700,000 years ago. Today, they are unlike any other group of killer whales—high in genetic diversity, which, along with their abundant prey, could be a factor in their current success.

“There’s the transients and there’s everybody else,” explains Lance Barrett-Lennard, director of the marine mammal research program at Ocean Wise’s Coastal Ocean Research Institute. “They’re quite a unique group, with an ancient distinct lineage.”

In the mid-1970s, Mike Bigg of DFO’s Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo, British Columbia led the research efforts to discover just how different the transients are from residents. “We thought [transients] were these oddballs, social outcasts, basically kicked out of the larger resident pods,” explains Ford, the emeritus federal whale scientist who first worked alongside Bigg as a UBC graduate student.

Over a decade, Bigg, Ford, Ellis, and other scientists pieced together the clues, and officially presented their findings on transients at the Society for Marine Mammalogy in Vancouver in 1985. Despite their strong resemblance to resident killer whales, transients speak a different “language,” have subtly distinct fins and body markings, travel a bigger range, and mix only with other transient groups. And, of course, they have an entirely different diet. “Some day they’ll be officially classified as a different species, I’m sure,” says Ford. Bigg won’t see that day. He died of leukemia in 1990, and Ford and other researchers would like to see transients renamed Bigg’s killer whales.

Today, researchers continue to explore what makes transients tick. Drones provide clear visual evidence of the physical differences in the two ecotypes, including the transients’ beefier build, and powerful teeth and jaws to dispatch larger prey.

In 2016, Barrett-Lennard used a drone to observe the hunting strategies of a greedy transient, part of a larger group, working a reef near Telegraph Cove, British Columbia. “As [the whales] checked out every crack and crevice where a seal might be hiding, this one already had a seal in its mouth … trying to get another one.”

Their hunting prowess is dramatic, as a YouTube search for transient killer whales will attest. One post titled “Transient orca punts a seal 80 feet into the air near Victoria” is jaw-dropping. “It’s kind of like a karate chop,” Ellis explains of the whale’s lethal tail swipe. “They have to do a sideways swipe to get a really hard hit in.” Desperate seals are known to jump onto the transoms of recreational fishing boats and sea lions hug the hulls of vessels to avoid killer whale attacks.

It takes a lot of shoreline hunting grounds to ensure the transients’ long-term survival. Researchers calculate that the population of transient whales requires an area of protected critical habitat extending three nautical miles off the BC coast and covering 40,358 square kilometers, bigger than Vancouver Island. They need that much space to ensure their sneak-attack hunting tactics work. “They need to keep moving constantly,” Ford explains. Once seals, sea lions, or porpoises are alert to the whales’ presence, they probably become more difficult to catch.

To be successful, transients have relatively few calls, and maintain silence while hunting. Research by Barrett-Lennard shows that transient echolocation typically consists of one or two cryptic clicks back to back every few minutes—just enough to improve navigation and orientation, but subtle enough to be masked by background ocean sounds. Transients become chatty during or after a kill—and are thought to use scream-like calls to frighten dolphins or porpoises into inlets or bays to be killed.

In 2014, transients herded dolphins into Departure Bay near Nanaimo and ferry passengers captured the feeding frenzy on video. A similar story unfolded near Salt Spring Island, British Columbia, in 2002, when transients drove a minke whale into the shallow waters of Ganges Harbour. The social calls were audible to witnesses. “Hundreds of people lined up on shore, half cheering for the killer whales and half for the minke to get away,” Ellis recalls. “It went on for a long time.”

In addition to employing cryptic echolocation, transients are thought to listen for the subtle sounds of their prey. “It might be something as quiet as a heartbeat or the sound of a harbor porpoise tearing the surface with its dorsal fin,” explains Barrett-Lennard. He has observed transients homing in on young seals calling for their mothers. “It’s like a shot went off, you practically see the whales jump, then they’ll turn and scoop the pup up. It’s effortless.” This use of subtle sound is why researchers speculate transient killer whales may be more vulnerable than residents to underwater vessel noise.

Jared Towers, a DFO research technician based at Alert Bay on northeastern Vancouver Island, is ever alert for the sounds of transients in an increasingly noisy ocean. His 1920s heritage house has a commanding view of Johnstone Strait, one of the best spots for summer sightings of killer whales in British Columbia. He picks up the sounds of transients on a hydrophone, and the calls are transmitted to the antenna on his roof via VHF signal. “You get an ear for it,” says Towers. “The transients almost sound a bit more eerie.”

His experience is that not all transient vocalizations are related to a kill. Juveniles are known to talk out of turn; in theory, that might reduce the chance of a successful kill, but it doesn’t seem to be slowing the growth of the overall population.

Shipping noise could be a much greater threat, although it is difficult to measure the impact. Towers observes that shipping noise might impair transients’ ability to find prey, and the population might even do better in a silent sea, since that is the way they evolved. On the other hand, they catch seals all the time despite vessel traffic in close proximity. He wonders whether the whales may actually use a vessel’s motor to mask their presence to potential prey. “On a daily basis in the Salish Sea, they’re killing seals all over the place and there are boats all over the place,” he says.

Some threats to the transients are so insidious they make no sounds at all.

As predators at the peak of an abundant food chain, transients have plenty of food at the moment, but being a top predator comes with costs, particularly in the populated and polluted waters of the Salish Sea—any toxins in the prey bioaccumulate in the whales.

A 2000 study published in Marine Pollution Bulletin found that levels of banned but persistent polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are 250 parts per million in transient killer whales, making them the “most contaminated cetaceans in the world,” carrying at least 300 times the level of pollutants than humans on an equal-weight basis, says lead author Peter Ross, vice president of research at the Ocean Wise Conservation Association. Research also shows that PCBs disrupt hormone physiology in killer whales, including the female reproductive hormone estrogen and the thyroid hormone. Understanding what this means to the health of the population is not easy, but the hormones play critical roles in the reproductive system and in growth and development. With both ecotypes of killer whales under threat by contaminants, noise, and disturbance—and residents facing the additional challenge of finding prey—any knock on their health can have serious consequences.

PCB levels in killer whales probably peaked in the early 1970s. Because the toxins take so long to leave the body, it’s expected to be 2090 before they are reduced to safe levels in 95 percent of the southern resident population. And the chemical industry moves on. PCBs are probably the number one threat, Ross notes, but there are more than 100,000 chemicals on the market, and untold numbers are finding their way into the whales’ environment.

Toxins are a major reason why transient killer whales are listed as threatened under Canada’s Species at Risk Act. Other factors include a relatively small population and a low reproduction rate of about one calf every five years.

Despite their toxic load, the transient population is faring better than the southern residents. Researchers believe that transients have so much food available that they don’t have to metabolize their blubber when food is scarce, which draws out the pollutants. Toxins released when chinook-deprived resident killer whales use their fat stores are thought to be contributing to high miscarriage rates and deaths of young animals. Adult females of both ecotypes carry fewer toxins than males because they offload pollutants onto their offspring during gestation and lactation.

Kenneth Balcomb has seen the whale issue as both pursuer and protector. As a zoology graduate in the early 1960s, he worked at whaling stations in California, Newfoundland, and Nova Scotia, tagging whales with stainless steel tubes fired into their back muscles and sorting through carcasses for ovaries and stomach contents, which gave clues to reproductive success and diet.

To Balcomb, the founder and senior scientist with the Center for Whale Research in Washington State, the transients’ secret to success is obvious. “It’s pretty clear to me [that] it comes down to whether or not there is food. All these other issues about toxins or boat noise and whale watching and all this crap is irrelevant. If you’ve got food you’ll survive and if you don’t you won’t. It’s straightforward.”

“It’s a bit more complex,” Ford says. “These different stressors do interact with each other.”

The transients’ ability to thrive against the odds is a source of amazement, not just to the scientific community but to those who watch whales for fun and profit.

**********

Back at Race Rocks, Malleson maneuvers the boat so we parallel the transients while they head westward, working the coastline for unsuspecting prey. Their breathing is strong and deliberate, their movements purposeful and in tighter formation than the residents. “That’s often the way with them, whereas the fish eaters are very spread out foraging,” Malleson says.

He winces when he spots a whale with an old scar from a satellite tag. Researchers used to practice their tagging techniques on the more numerous transients before trying them on residents. “It almost looks like a protruding barb,” says Malleson, peering for a better look. “I think they left some hardware in there. I’m not a fan of them. Never was.” The invasive tactic ended after scientists with the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration fired a dart that caused an infection leading to the death of an otherwise healthy male resident killer whale in 2016.

Malleson finds another reason for optimism—the youngest whale in the group is only a few months old. Its skin sports an orange hue that should turn white in its first year. The youngster practices a breach, lunging straight up from the water, but it comes off like an awkward pirouette. “Look at that little guy. Full of piss and vinegar.”

As the sky starts to rain and the killer whales continue their journey, Malleson reluctantly turns the boat around and heads home. The resident male is nowhere to be seen, all but forgotten in the moment. What remains is the wake of a powerful ascending predator that generates terror among its prey, awe among humans, and a sense of limitless possibilities.

No longer captives of humanity, they are swimming with a swagger, hunting where they please, and regaining their rightful position in a vast, bountiful sea.

Today, we witness the rise of the transients.

Related Stories from Hakai Magazine: