Last year was an excellent one for amateur astronomers. Stargazers in the United States saw two total lunar eclipses, a spectacular “ring of fire” solar eclipse and a rare alignment of the planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. This year promises another amazing set of celestial events, including dark skies for the two most anticipated meteor showers: the Perseids and the Geminids. To watch these and other phenomena, all you’ll need is a dark location, weather-appropriate gear and occasionally a set of binoculars. To help you plan your nights out in 2023, we’ve compiled a list of the ten biggest celestial events of the year.

February 2: Comet C/2022 E3 comes close to Earth

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0a/5b/0a5b1bd2-a427-47d4-93e9-fd285b932f48/01_c2022e3_ztf_bartlett800.jpg)

In early February, the comet C/2022 E3 will travel within about 26.4 million miles of our planet—the closest it’s been to Earth since Homo sapiens began settling in Europe and Asia from Africa, according to KTLA’s Eric Henrikson and Cameron Kiszla.

While the brightness of comets can be unpredictable, this one may be visible to the naked eye under dark skies, though those with binoculars or a telescope will have a better chance of seeing it. Stargazers in the Northern Hemisphere may be able to spot the comet in the morning sky in the northwest during January, while those in the Southern Hemisphere should keep an eye out starting in early February. The comet has a distinctive green color and faint long tail.

March 1: Venus-Jupiter conjunction

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/04/bb/04bbe531-647b-4890-919e-20fdd0cf0253/02_jupiter_venus_2022apr30_hsv-003-scaled_web.jpg)

In astronomy, a conjunction occurs when a planet appears close to a moon, another planet or a star. Conjunctions occur fairly frequently and have “no profound astronomical significance, but they are nice to view,” according to NASA.

During the first few months of the year, the two brightest planets will begin to converge in the southwestern sky, and on March 1, they will reach their closest points to each other. You should be able to see both with your bare eyes, though you can also see them in the same field of view with even the tiniest backyard telescope, writes National Geographic’s Andrew Fazekas. Though the two will appear relatively close, they are actually millions of miles apart. Look west-southwest at dusk to see the two planets together.

April 15 to April 29: Lyrid meteor shower

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/98/be/98be6593-261d-4d5c-bfaa-ba4b6b8a3978/03_gettyimages-685838788_web.jpg)

Meteor showers occur when the Earth passes through debris left behind from comets and asteroids, which is why they occur at around the same time each year. The Lyrids originate from the comet Thatcher, which orbits the sun about every 415 years. This is one of the oldest recorded showers, with observations dating back to 687 B.C.E., writes Daisy Dobrijevic for Space.com.

This year’s shower will peak on the night of April 22, and the viewing conditions will be favorable—the waxing crescent moon will only be 6 percent illuminated, Dobrijevic writes. Observers are usually able to see about 18 meteors per hour in a clear, dark sky, though on very rare occasions, the Lyrids can surprise viewers with as many as 100 meteors in an hour.

For the best stargazing, find a dark area between moonset and sunrise. Lie flat on your back with your feet facing east and look up at the sky, NASA recommends.

April 15 to May 27: Eta Aquarid meteors

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/56/73/5673ec9a-a523-4176-9e48-7d0d6049dd8a/04_eta_aquarid_meteor_at_dawn_-_flickr_-_ikewinski_web.jpg)

This shower is known for its fast meteors that leave long, glowing trails. Eta Aquarid meteors can travel at about 148,000 miles per hour into Earth’s atmosphere, according to NASA. Their radiant—or the point from which they appear—is the constellation Aquarius.

These meteors come from the comet Halley, which completes an orbit around the sun about once every 76 years. This comet also produces the Orionid meteor shower, which occurs in October. Halley was last seen by casual observers in 1986 and is projected to make another appearance in 2061.

This year’s Eta Aquarids will peak the night of May 5 to May 6. Unfortunately, the full moon will appear on May 5, 2023, but don’t let that deter you. A significant outburst with meteors raining down at twice their usual rate could occur, and while the moon may wash out many, it still “could be a pretty decent show,” Bill Cooke, the lead for the Meteoroid Environment Office at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, tells Space.com’s Dobrijevic. These meteors are best viewed in the Southern Hemisphere, but they can also be seen north of the equator at a usual rate of about 10 to 30 per hour in good conditions. Try looking up during pre-dawn hours on or around the peak.

July 14 to September 1: Perseid meteor shower

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f0/d2/f0d2b2b1-9fe5-4e39-b5a5-28db998f6242/05_51371961714_97a3fd9923_o_web.jpg)

The Perseid meteor shower is one of the best of the year. Bright, frequent meteors with long tails will light up the sky at rates of about 50 to 100 per hour. The shower happens as Earth passes through debris left behind by the comet Swift-Tuttle, and it peaks as the Earth moves through the densest portion. Last year’s Perseids coincided with the full moon, making some shooting stars difficult to see. But this year, the shower will reach its spectacular peak two days before the new moon on August 11 and 12.

For the best viewing experience, Royal Museums Greenwich recommends heading to a dark location and giving your eyes 15 minutes to adjust, which means taking a break from checking your phone.

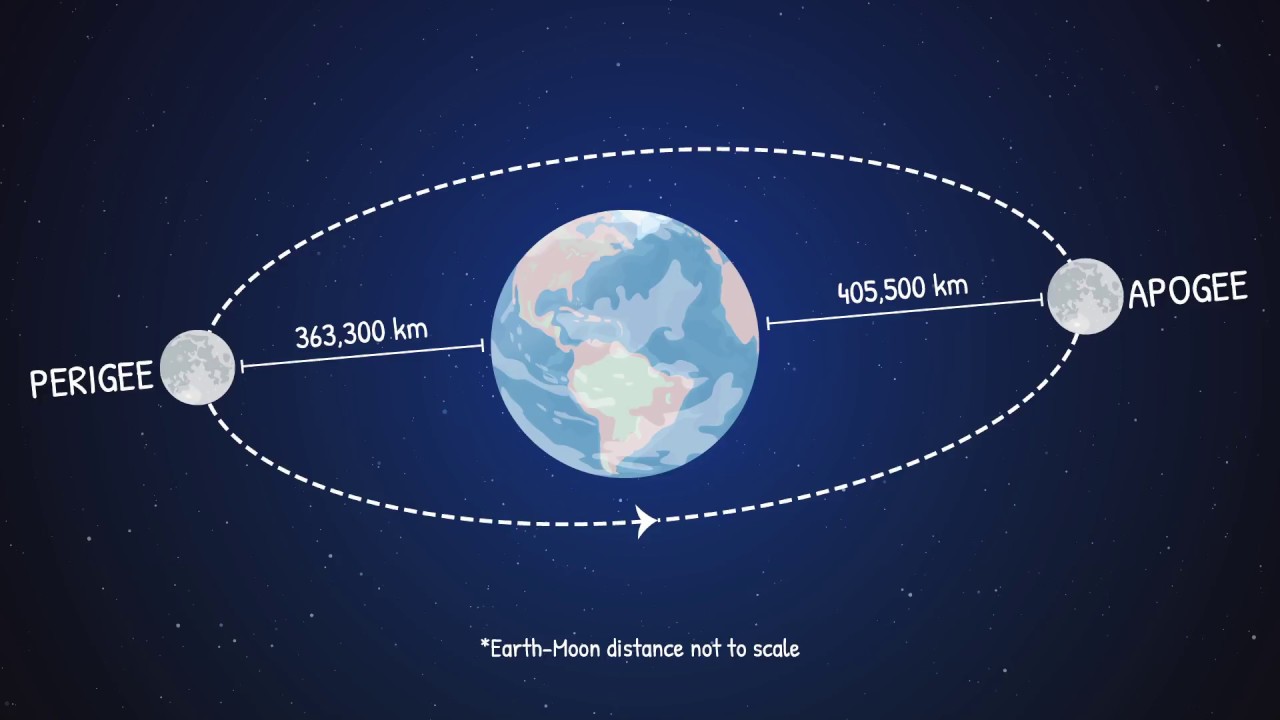

August 31: A super blue moon

Those looking at the sky on the night of August 31 may notice that the full moon appears slightly larger and brighter than usual. That’s because the moon will be the closest in its elliptical orbit to Earth, making it a supermoon. Four supermoons will appear in a row this year—on July 3, August 1, August 31 and September 29.

Because the month of August will see two full moons, the second is considered a blue moon. Blue moons happen every 2.5 years, and the last one occurred in August 2021.

September 26 to November 22: Orionids

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/72/00/7200d014-3be6-48fb-a9b6-b776235e42a6/07_pia17485_web.jpg)

The Orionids are not typically as strong as the Perseids or the Geminids, but they are still worth watching. From a dark location, viewers can see about 10 to 20 meteors per hour at the shower’s peak, which falls around the morning of October 22, per EarthSky’s Deborah Byrd.

Like the Eta Aquarids, this shower comes from the comet Halley, named after the English astronomer Edmond Halley. He was the first to calculate the comet’s orbit, accurately predicting its return in 1758—16 years after his death.

This year, the moon will set by midnight on the peak night, providing little interference to viewers who look up in the early hours of the morning. While the meteors appear to originate from the constellation Orion the Hunter, you will be able to see shooting stars anywhere in the sky.

October 14: Annular solar eclipse

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5b/10/5b10cfd4-10e8-4499-bf0f-a2be94ba02ea/08_74_annular_eclipse_detail_web.jpg)

In mid-October, an annular solar eclipse will be visible from the southwestern U.S. Solar eclipses occur when the moon passes between the Earth and the sun. But because the moon won’t entirely cover the sun this year, a dazzling glowing circle, or a “ring of fire,” will be visible from certain locations. Such an annular solar eclipse can last for up to 12 minutes and 30 seconds, per Space.com’s Dobrijevic and Joe Rao, though this year, the maximum duration is about five minutes in the U.S.

In the U.S., the annular eclipse will begin in Oregon at 9:13 a.m. Pacific Daylight Time and cross through several states before ending in Texas at 12:03 p.m. Central Daylight Time, according to NASA. Folks outside this narrow path won’t see the ring-shaped eclipse, but they can catch a partial eclipse—if the weather cooperates. Remember to always use eye protection when looking at a solar eclipse.

October 28: Partial lunar eclipse

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c5/35/c5352d6c-df14-4ef0-956a-74500c4e07fd/09_visibility_lunar_eclipse_2023-10-28_web.jpg)

Last year, the U.S. was treated to two total lunar eclipses. A total lunar eclipse occurs when the Earth’s shadow obscures the entire surface of the moon, while a partial eclipse takes place when the moon passes only partly through Earth’s dark shadow, or umbra. A third type of eclipse called a penumbral lunar eclipse is more subtle and occurs when the Earth’s fainter outer shadow, called the penumbra, is cast on the moon.

The penumbral eclipse will only be visible in the U.S. on the East Coast. If you’re watching from there, the moon will be below the horizon for the entire partial eclipse, which will begin at 3:35 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time and end at 4:52 p.m. But if you look closely, you may still be able to catch the Earth’s faint penumbra on the moon’s surface after it rises in your area. The penumbral eclipse will end at 6:26 p.m. Eastern.

Unlike a solar eclipse, you don’t need any equipment to view a lunar eclipse.

November 19 to December 24: Geminid meteor shower

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c0/11/c011fb81-00d3-4564-bc06-ea9fa9c5cff5/10_gettyimages-1237222317_web.jpg)

The Geminids are another fan favorite and one of the last meteor showers of the year. This shower is known for its speedy meteors—they can travel 78,000 miles per hour, more than 40 times faster than a speeding bullet, per NASA.

Unlike many other showers, the Geminids come from a rocky celestial object called an asteroid rather than an icy comet. Scientists aren’t exactly sure how the asteroid, called Phaethon, could lead to a meteor shower, but some theorize that it may actually be a dead comet—or a comet that has lost its icy shell, according to NASA.

Phaethon measures only roughly three miles in diameter, which is surprising considering the amount of debris it leaves behind. Adding to its intrigue, Phaethon appears to brighten as it approaches the sun, as a comet would. This asteroid comes closer to the sun than any other named asteroid, which is why it’s named after the son of the sun god Helios.

The most meteors are predicted to rain down on the nights of December 13 and 14, with the possibility of stargazers seeing 120 meteors per hour. Last year’s waning gibbous moon resulted in only about 30 to 40 visible meteors per hour in the Northern Hemisphere. But a young waxing crescent moon will set early in the evening this year on the peak, providing a dark sky for observers, write EarthSky’s Byrd and Kelly Kizer Whitt. The Geminids are best viewed around 2 a.m. local time, and you should be able to see meteors in all parts of the sky.

:focal(800x602:801x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/39/82/3982d8c6-e30d-4c9a-9ea6-2d2b20696e8c/main_gettyimages-1242638331_web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MargaretOsborne.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MargaretOsborne.png)