Ten Enduring Myths About the U.S. Space Program

Outer space has many mysteries, among them are these fables about NASA that have permeated the public’s memory

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/NASA-space-myths-moon-landing-631.jpg)

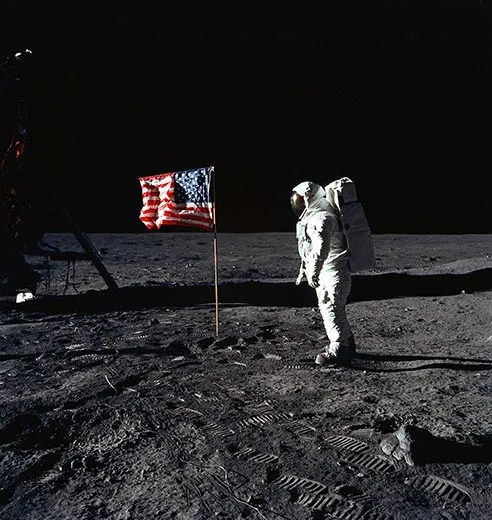

1. “The U.S. space program enjoyed broad, enthusiastic support during the race to land a man on the Moon.”

Throughout the 1960s, public opinion polls indicated that 45 to 60 percent of Americans felt that the government was spending too much money on space exploration. Even after Neil Armstrong’s “giant leap for mankind,” only a lukewarm 53 percent of the public believed that the historic event had been worth the cost.

“The decision to proceed with Apollo was not made because it was enormously popular with the public, despite general acquiescence, but for hard-edged political reasons,” writes Roger D. Launius, the senior curator at Smithsonian’s divison of space history, in the journal Space Policy. “Most of these were related to the Cold War crises of the early 1960s, in which spaceflight served as a surrogate for face-to-face military confrontation.” However, that acute sense of crisis was fleeting—and with it, enthusiasm for the Apollo program.

2. “The Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI) is part of NASA.”

The SETI Institute is a private, nonprofit organization consisting of three research centers. The program is not part of NASA; nor is there a government National SETI Agency.

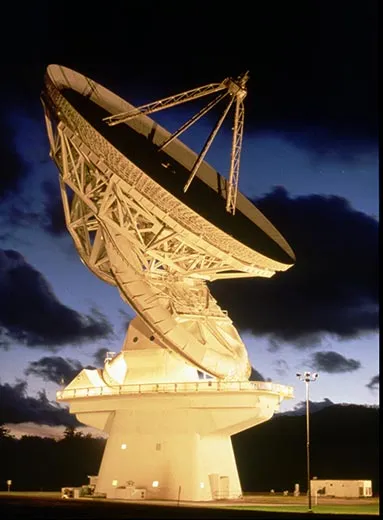

NASA did participate in modest SETI efforts decades ago, and by 1977, the NASA Ames Research Center and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) had created small programs to search for extraterrestrial signals. Ames promoted a “targeted search” of stars similar to our sun, while JPL—arguing that there was no way to accurately predict where extraterrestrial civilizations might exist—endorsed a “full sky survey.”

Those plans came to fruition on October 12, 1992—the 500-year anniversary of Columbus’ discovery of the New World. Less than a year later, however, Nevada Senator Richard Bryan, citing budget pressures, successfully introduced legislation that killed the project, declaring that “The Great Martian Chase may finally come to an end.”

While NASA no longer combs the skies for extraterrestrial signals, it continues to fund space missions and research projects devoted to finding evidence of life on other worlds. Edward Weiler, an astrophysicist and associate administrator of the Science Mission Directorate at NASA headquarters, told Smithsonian magazine: “As long as we have water, energy and organic material, the potential for life is everywhere.”

3. “The Moon landing was a hoax.”

According to a 1999 Gallup poll, 6 percent of Americans doubted that the Moon landing actually happened, while another 5 percent declared themselves “undecided.”

The Moon landing conspiracy theory has endured for more than 40 years, thanks in part to a thriving cottage industry of conspiracy entrepreneurs—beginning in 1974, when technical writer Bill Kaysing produced a self-published book, We Never Went to the Moon: America's Thirty Billion Dollar Swindle.

Arguing that 1960s technology was incapable of sending astronauts to the Moon and returning them safely, authors and documentary filmmakers have claimed, among other things, that the Apollo missions were faked to avoid embarrassment for the U.S. government, or were staged to divert public attention from the escalating war in Vietnam.

Perhaps one reason for the durability of the Moon hoax theory is that it is actually several conspiracy theories wrapped up in one. Each piece of “evidence” has taken on a life of its own, including such accusations as: the astronauts’ film footage would have melted due to the extreme heat of the lunar surface; you can only leave a footprint in moist soil; and the American flag appears to be fluttering in the non-existent lunar wind.

The scientific debunking of these and other pieces of evidence can be found at NASA’s website—or, at least, that’s what we’ve been led to believe.

4. “During the 1990s, NASA deliberately destroyed its own Mars space probes.”

Mars is the planetary equivalent of Charlie Brown’s kite-eating tree. During the 1990s, NASA lost three spacecraft destined for the Red Planet: the Mars Observer (which, in 1993, terminated communication just three days before entering orbit); the Mars Polar Lander (which, in 1999, is believed to have crashed during its descent to the Martian surface); and the Mars Climate Orbiter (which, in 1999, burned up in Mars’ upper atmosphere).

Conspiracy theorists claimed that either aliens had destroyed the spacecraft or that NASA had destroyed its own probes to cover-up evidence of an extraterrestrial civilization.

The most detailed accusation of sabotage appeared in a controversial 2007 book, Dark Mission: The Secret History of NASA, which declared “no cause for the [Mars Observer’s] loss was ever satisfactorily determined.”

Dark Horizon “came within one tick mark of making it onto the New York Times bestsellers list for paperback non-fiction,” bemoaned veteran space author and tireless debunker James Oberg in the online journal The Space Review. In that same article, he points out the book’s numerous errors, including the idea that there was never a satisfactory explanation for the probe’s demise. An independent investigation conducted by the Naval Research Laboratory concluded that gases from a fuel rupture caused the Mars Observer to enter a high spin rate, “causing the spacecraft to enter into the ‘contingency mode,’ which interrupted the stored command sequence and thus, did not turn the transmitter on.”

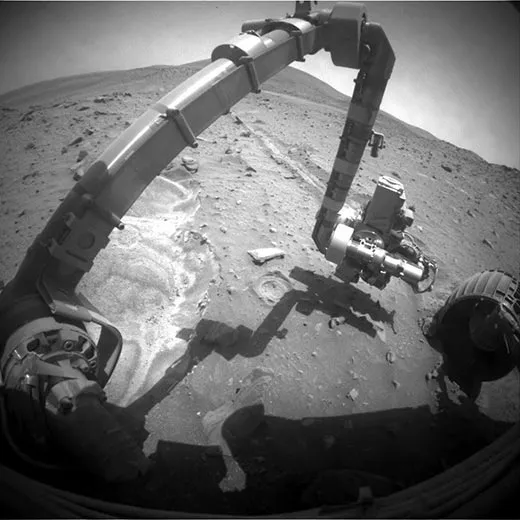

NASA did have a noteworthy success in the 1990s, with the 1997 landing of the 23-pound Mars rover, the Pathfinder. That is, of course, if you believe it landed on Mars. Some say that the rover’s images were broadcast from Albuquerque.

5. “Alan Shepard is A-Okay.”

Several famous inventions have been mistakenly attributed to the space program—Tang, Velcro and Teflon, just to name a few.

Most of these claims have been widely debunked. However, one of the most enduring spinoffs attributed to NASA is the introduction of the expression “A-Okay” into everyday vernacular.

The quote is attributed to astronaut Alan Shepard, during the first U.S. suborbital spaceflight on May 5, 1961. The catchphrase caught on—not unlike the expression “five-by-five,” which began as a radio term describing a clear signal.

Transcripts from that space mission, however, reveal that Shepard never said “A-Okay.” It was NASA’s public relations officer for Project Mercury, Col. John “Shorty” Powers, who coined the phrase—attributing it to Shepard—during a post-mission press briefing.

6. “NASA's budget accounts for nearly one-fourth of government spending.”

A 2007 poll conducted by a Houston-based consulting company found that Americans believe that 24 percent of the federal budget is allocated to NASA. That figure is in keeping with earlier surveys, such as a 1997 poll that reported the average estimate was 20 percent.

In truth, NASA’s budget as a percentage of federal spending peaked at 4.4 percent in 1966, and hasn’t risen above 1 percent since 1993. Today, the U.S. space program accounts for less than one-half of 1 percent of all federal spending.

A 2009 Gallup poll found that most Americans—when told the actual amount spent by the space program—continue to express support for the current level of funding for NASA (46 percent) or an expansion of it (14 percent).

7. “The STS-48 UFO”

Photographs and videos taken by U.S. spacecraft have opened up a whole new vista for alleged UFO sightings. Among the most famous of these is a video sequence recorded by the space shuttle Discovery (Mission STS-48), while in orbit on September 15, 1991.

A description of the video appears on numerous websites and newsgroups:

“A glowing object suddenly appeared just below the horizon and ‘slowly’ moved from right to left and slightly upward in the picture. Several other glowing objects had been visible before this, and had been moving in various directions. Then a flash of light occurred at what seemed to be the lower left of the screen; and the main object, along with the others, changed direction and accelerated away sharply, as if in response to the flash.”

UFO enthusiasts claim the video shows that the space shuttle was being followed by extraterrestrial spacecraft, which then fled in response to a ground-based laser attack. The footage was aired by media outlets such as CNN’s “Larry King Live” (which challenged viewers to “Judge for yourself”).

The UFOs were, in fact, small fragments of orbital flotsam and jetsam. As space author James Oberg has explained, there are more than 50 sources of water, ice and debris on the shuttle—including an air dump line, a waste water dump line and 38 reaction control system (RCS) thrusters that are used for attitude control and steering.

So, his explanation for the events in the video?

“The RCS jets usually fire in 80-millisecond pulses to keep the shuttle pointed in a desired direction….These jets may flash when they ignite if the mixture ratio is not quite right…When small, drifting debris particles are hit by this RCS plume they are violently accelerated away from the jet. This is what is seen [in the video], where a flash (the jet firing) is immediately followed by all nearby particles being pushed away from the jet, followed shortly later by a fast, moving object (evidently RCS fuel ice) departing from the direction of the jet.”

8. “The Fisher Space Pen ‘brought the astronauts home.’”

In his book, Men from Earth, Buzz Aldrin describes a brief moment when it seemed that the Apollo 11 lander might be stranded on the lunar surface: "We discovered during a long checklist recitation that the ascent engine's arming circuit breaker was broken off on the panel. The little plastic pin (or knob) simply wasn't there. This circuit would send electrical power to the engine that would lift us off the Moon.”

What happened next is the stuff of legend. The astronauts reached for their Fisher Space Pen—fitted with a cartridge of pressurized nitrogen, allowing it to write without relying on gravity—and wedged it into the switch housing, completing the circuit and enabling a safe return.

True enough, except that the astronauts didn’t use the Fisher Space Pen. Aldrin relied on a felt-tip marker, since the non-conductive tip would close the contact without shorting it out, or causing a spark.

The myth endures, in part, because the Fisher Space Pen company knew an opportunity when it saw one. They began promoting their product as the writing instrument that had “brought the astronauts home.”

9. “President John F. Kennedy wanted America to beat the Soviet Union to the Moon.”

Had JFK not been assassinated in 1963, it is possible that the space race to the Moon would instead have been a joint venture with the Soviet Union.

Initially, the young president saw winning the space race as a way to enhance America’s prestige and, more broadly, to demonstrate to the world what democratic societies could accomplish.

However, JFK began to think differently as relations with the Soviet Union gradually thawed in the aftermath of the Cuban missile crisis and the costs of the Moon program became increasingly exorbitant. Nor was America confident at that time that it could beat the Soviet Union. And, in his recent book, John F. Kennedy and the Race to the Moon, space historian John Logsdon notes that the president also believed that the offer of a cooperative mission could be used as a bargaining chip in Washington’s diplomatic dealings with Moscow.

In a September 1963 speech before the United Nations, JFK publicly raised the possibility of a joint expedition: “Space offers no problems of sovereignty…why, therefore, should man’s first flight to the moon be a matter of national competition? Why should the United States and the Soviet Union, in preparing for such expeditions, become involved in immense duplications of research, construction and expenditure?”

But, the prospect of a U.S.-Soviet mission to the Moon died with Kennedy. Winning the space race continued to drive the Apollo program. Eventually, “the U.S. space program, and particularly the lunar landing effort,” Logsdon writes, became “a memorial” to JFK, who had pledged to send a man to the Moon and return him safely by the end of the decade.

10. “No Buck Rogers, No Bucks.”

For decades, scientists and policy-makers have debated whether space exploration is better suited to human beings or robots.

While there are many solid arguments in favor of manned exploration, the most frequently cited one is arguably the least convincing: without spacefaring heroes, the nation’s interest in space science and exploration will dwindle. Or, to paraphrase a line from The Right Stuff, “no Buck Rogers, no bucks.”

“Don’t believe for a minute that the American public is as excited about unmanned programs as they are about manned ones,” cautioned Franklin Martin, NASA’s former associate administrator for its office of exploration, in an interview with Popular Science. “You don’t give ticker tape parades to robots no matter how exciting they are.”

But the American public’s fascination with images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope and the sagas of the robotic Mars rovers Pathfinder (1997), Spirit (2004) and Opportunity (2004, and still operating) belies the assertion that human beings are vital participants. Proponents of unmanned space exploration make the case that the most essential element for sustaining public interest are missions that produce new images and data, and which challenge our notions of the universe. “There is an intrinsic excitement to astronomy in general and cosmology in particular, quite apart from the spectator sport of manned spaceflight,” writes the famed philosopher and physicist Freeman Dyson, who offers a verse from the ancient mathematician Ptolemy: “I know that I am mortal and a creature of one day; but when my mind follows the massed wheeling circles of the stars, my feet no longer touch the earth.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mark-strauss-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mark-strauss-240.jpg)