Ten Things We’ve Learned about Sharks Since Last Shark Week

In light of Shark Week 2017, here are some revelations about the fearsome fish we’ve made in the past year

:focal(2648x822:2649x823)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/82/48/82486d30-d513-4ec4-b108-e41c3cd2900f/apb61x.jpg)

It's that time again to be afraid of entering the water: The Discovery Channel's 29th annual "Shark Week" is here. Whether you love them, fear them, or feel yourself inexplicably drawn to them, it's clear these formidable fish play an outsized role in the cultural consciousness. To celebrate their contributions to the zeitgeist, here are 10 things we've discovered about these animals in the past year.

- As a group, sharks have been around for roughly 450 million years. But when it comes to individual lifespan, there's one species that appears to be the longest-lived vertebrates ever discovered. Unlike the tropical sharks many are familiar with, Greenland sharks live in the cold waters near the Arctic, giving them a slow metabolism rate that's "just above a rock," according to one shark researcher. This slow-motion living means they can survive for more than 400 years, but it also means that the sharks reproduce extremely slowly. This puts them at greater risk of extinction if many of them are killed off.

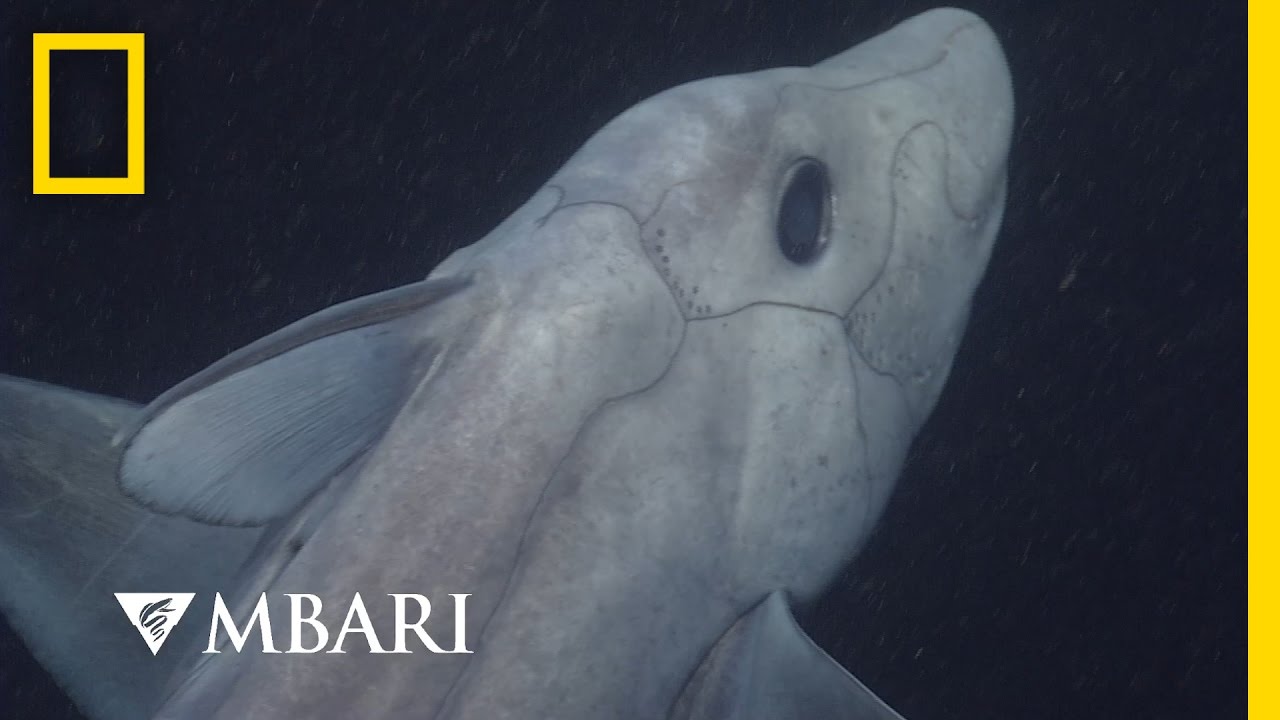

- While we’re on the topic of reproduction, it turns out that some sharks do it in a very strange way. The mysterious "ghost sharks”—which get their name because they live deep underwater and are rarely seen—were found recently to have retractable sex organs on their heads. These organs have hooks that male ghost sharks use to grasp female ghost sharks during mating, which "does not seem to be a very pleasant experience for the females," according to biologist Brit Finucci. Thankfully, female ghost sharks appear also to be able to store sperm for years in special storage banks in their bodies, waiting until the right time to conceive.

- Last August, the conservation group Ocearch made waves when one of its expeditions uncovered a rare great white shark nursery in the shallow waters just off the coast of New York. This was the first such nursery found in the northern Atlantic Ocean, and researchers believe the sharks spend the first 20 years of their life there. In general little is known about the migratory patterns of young sharks, making this "the most important significant discovery we’ve ever made,” according to Fischer.

- Reef sharks are often depicted as the alpha predators of their habitats, akin to lions in the savannas of Africa. But that’s a myth popularized by humans, argue researchers studying fish in the Caribbean. "When we did our analysis, for each of the studies we looked at there was either no evidence of that kind of relationship or it was ambiguous or weak," ecologist Peter Mumby told Hakai Magazine. Instead, in many areas where sharks were fished, the population levels of herbivore fish didn't change substantially, meaning the sharks’ level of influence on their environments was lower than previously thought. Only a few of the largest shark species, such as tiger sharks, actually play the role of apex predator.

- Larger than many of those sharks, however, was the newly described species Megalolamna paradoxodon, which grew to the size of a car when it roamed the world’s oceans. These giants lived 20 million years ago, and were identified in the past year from teeth found in the Pacific Ocean. Estimating from the teeth, researchers were able to extrapolate the extinct species to be about 12 feet in length, much larger than most humans, though smaller than the infamous great white shark, which can grow up to 16 feet long. The species may have been a close relative of other ancient sharks that grew to be five times that size.

- Many sharks are under threat worldwide from being killed illegally for their meat and fins, as well as getting caught in nets targeting other fish. Now scientists find that one solution to saving these animals might actually be encouraging fishing of them—legally. A study this year found that currently only about 4 percent of shark fishing is managed sustainably. A shark fishing policy that takes into account certain sharks’ ages and reproductive cycles, the authors say, could aid greatly in the quest to keep shark populations healthy.

- California's great white sharks make a mysterious pilgrimage every year to a remote spot in the ocean, and scientists want to know why. “I think of it like Burning Man,” biologist Salvador Jorgensen told Slate. “You have all these Bay Area white sharks, and every year they head out into this white shark café, out into the desert of the ocean—and we’re not exactly sure what they’re doing out there.” He has worked to develop special durable cameras that can be attached to tags on the fins of some of these sharks, which he plans to do this fall in order to solve the mystery for good.

- Fishermen and scientists have been coming across more and more two-headed sharks in recent years. It still isn't clear what's causing this uptick in mutations, and the rarity of finding specimens may mean that we're just seeing more of a natural phenomenon. But some biologists suspect that infections, pollution or possibly even declining population from shark overfishing is causing more genetic mutations.

- In her 2016 book Grunt, science writer Mary Roach introduced readers to a top secret project after World War II that aimed to use sharks as weapons. No, it wasn't trying to set sharks loose on unwitting sailors—the U.S. Navy was instead hoping to use sharks to deliver bombs secretly. Special headgear on the sharks would use electric shocks to guide the sharks to their destinations, where the bombs they carried would be detonated. Fortunately for the sharks involved, the project ran from 1958 to 1971 with little success before being discontinued.

- Thanks to Hollywood sharks have little need to prove their toughness, but a study published this month highlights just how unflappable these creatures can be. The study documented a lemon shark that swallowed a steel piece of fishing equipment that pierced the shark’s stomach. The shark not only survived this injury, but it managed to get rid of the metal object by pushing it through its skin and out of its body. Another recent study documented just how many strange things tiger sharks manage to consume. The research collected observations of the sharks from 1983 to 2014, finding that the fish consumed 192 unique meals ranging from birds, bats and porcupines to trash like bags of chips and even condoms.