The Call of the Panama Bats

Scientist Elisabeth Kalko uses high-tech equipment to track and study the 120 bat species in the region

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Noctilio-leporinus-catches-fish-631.jpg)

I’m sitting in a boat, anchored in a secluded cove of the Panama Canal, waiting for the sun to set. Occasionally, the mild aftershock of a freighter passing through the center of the canal rocks the boat. But for the most part, the muddy water is calm.

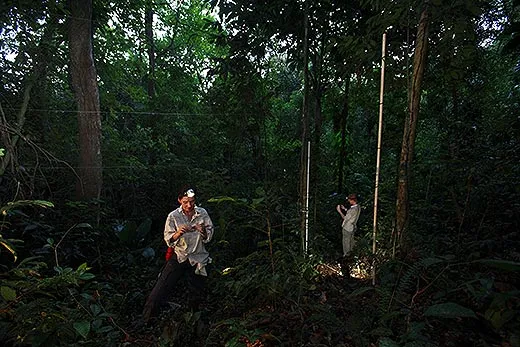

My hosts, bat expert Elisabeth Kalko and Ben Feit, a graduate student studying under her tutelage, are setting up their sound equipment in the last remaining light. “The transition between day and night happens so fast,” says Kalko. She waxes poetic—on the cutout-like quality of the silhouetted trees and the rattling cicada orchestra. Her fine-tuned ear isolates the croaks of frogs and the croons of other creatures, and she mimics them for my untrained ear. Hear that? I imagine she can almost tell time by the rhythm of the forest’s pulsing soundtrack, she knows it so well.

Since 2000, Kalko, who is jointly appointed as the head of the experimental ecology department at the University of Ulm in Germany and a staff scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), has been making two trips a year, usually for a month each time, to Panama’s Barro Colorado Island (BCI). The six-square-mile island, where STRI has a field station, is about a 40-minute ferry ride from Gamboa, a small canal town north of Panama City. A hot bed for biodiversity, close to half of Panama’s 220 mammal species live and reproduce on the island.

The bats are what draw Kalko. Around 120 bat species—a tenth of the species found worldwide—live in Panama, and of those, 74 can be found on BCI. Kalko has worked closely with a quarter of them and estimates she has observed about 60 in an effort to better understand the various behaviors that have allowed so many species to coexist.

She has taken me to “Bat Cove,” just a five-minute boat ride from BCI’s docks, to get a glimpse of her work. Just inside the forest, I’m told, is a 65-foot-tall hollowed tree with a rotting pile of guano, scales and fish bones at its base—the roost of Noctilio leporinus. The greater bulldog bat, as it’s more commonly known, is the only bat on the island with fish as its primary diet. Using echolocation to locate swimming fish making ripples in the water’s surface, it swoops down over the water, drags its long talons and snatches its prey. In flight, it curls its head down to grab the fish, then chews it and fills its cheek pouches like a hamster.

Kalko holds a bat detector above her head. The device picks up the high frequency echolocation calls of nearby bats and runs them through a buffer to make them audible. Slowed down, the calls sound like the chirps of birds. Feit watches as sonograms of the sounds appear on his laptop. Kalko has compiled a library of these calls and, from their frequencies and patterns, can identify the species of the caller. As we are sitting, listening, she differentiates between aerial insectivores above the canopy, fruit-eating bats in the forests and fishing bats over the water. She can even determine their stage of foraging, meaning if they are searching or plunging in for a kill, from the cadence of the calls. Her deep passion for bats is contagious, and it puts me at ease, given the situation. When the chirps come in loud on the detector, her assistant casts his headlamp across the surface of the water. Greater bulldog bats often have a reddish color fur and can have a wingspan measuring over two feet, but their fluttering wings are the only things visible as they are fishing. “Wah,” Kalko exclaims each time a bat flits by the boat.

Her shrieks are in awe, not fear. Kalko attributes bats’ historically bad reputation to people’s tendency to misinterpret encounters with them as attacks. She calls to mind popular images of a panicky bat accidentally trapped indoors and the cartoonish scene of a bat landing in a woman’s hair. Imaginations really run wild with the carnivorous, blood-sucking vampire bat, as well. But it is her hope that people come to see the beneficial roles bats play, first and foremost as pollinators and mosquito eaters. “Research pays off,” says Kalko. Scientists, for example, are finding that a chemical in vampire bat saliva that acts as an anticoagulant could potentially dissolve blood clots in humans with less side effects than other medications.

Kalko’s greatest discoveries are often made when she catches bats in mist nets, or volleyball-like nets that safely trap an animal in flight, and studies them in a controlled environment. She sets up experiments in flight cages at BCI’s field station and captures their movements with an infrared camera. One of her latest endeavors has been to team up with engineers from around the world on the ChiRoPing project, which aims to use what is known about sonar in bats to engineer robotic systems that can be used where vision isn’t feasible.

In her research, Kalko has found bats that live in termite nests; fishing bats off the coast of Baja, Mexico, that forage miles into the ocean; and bats that, unlike most, use echolocation to find stationary prey, like dragonflies perched on leaves. And her mind is always spinning, asking new questions and imagining how her findings can be applied in some constructive way to everyday life. If bats and ants can coexist with termites, do they produce something that is termite repellant? And if so, can humans use it to stop termites from destroying their houses and decks? Fruit-eating bats essentially soak their teeth in sugar all the time and yet they don’t have cavities. Could an enzyme in their saliva be used to fight plaque in humans?

Early in the night, several bats circle the area. Kalko recalls a feeding frenzy of small insectivores called molossus bats she once witnessed in Venezuela, when she was “surrounded by wings.” This is far from that, mainly because it is just a day or two after the full moon, when bats and insects are considerably less active. As the night wears on, we see less and less. Kalko emphasizes the need for patience in this type of fieldwork, and jokes that when she is in Panama, she gets a moon burn.

“So many billions of people in the world are doing the same thing, day in and day out,” she says, perched on the bow of the boat, as we motor back to the field station. “But we three are the only people out here, looking for fishing bats.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)