The “Girls on Ice” Share Their Experiences in the Field

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/life_dsc01710.jpg)

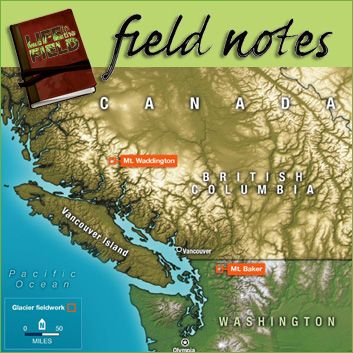

Saturday, August 12, 2006: Day Seven on Mount Baker

"Good morning ladies, it's time to get up!" Erin Pettit gleefully yelled in the cold mountain morning. Erin, an instructor from Portland State University, was our leader. She was greeted with a series of harrumphs and mumbled protests. Tiffany, head cook of the day, struggled to extract herself from her damp tent by crawling over Amy and Molly. She unzipped the door, and a blast of cold air filled our humble abode, much to our dismay. The small pond by us was frozen into an intricate crisscrossed pattern, and the stream had stopped flowing!

After a hot breakfast of oatmeal and cocoa, we broke camp around 10 a.m. and headed for Easton Glacier. This was our last day on the glacier. We hiked about 50 feet up to the Macalfe Moraine, a ridge of rocky debris the glacier left many years before. Underneath us, the rocks got looser and the amount of vegetation decreased. Erin says these were signs that the glacier covered the ground under us probably less than 100 years ago. After hiking for about 30 minutes, we reached the perfect snow patch at the base of huge crevasses on the side of the glacier. Our crampons were tightly strapped, along with our harnesses, which were buckled within seconds. We barely got on the glacier before Cece Mortenson, a mountaineering guide, spied our next destination to explore: a crevasse high above the snow patch we just left. We all slowly climbed up the steep, icy, rocky, muddy slope. We looked down the open crevasse and could actually see the ground beneath the glacier. After getting a quick peek, we slowly made our way back down using our perfected cramponing skills. We had been walking only ten minutes before we stumbled upon our next adventure. All of a sudden Cece told us to drop our packs and follow her. We saw her slowly disappear into what seemed to be a small cave. As we got farther into the cave, we realized its size. All 11 of us fit in with plenty of elbowroom. Despite the slowly dripping mud, we managed to take heaps of pictures and even noticed the huge boulder that had carved out the cave as the glacier flowed over it and left a gap between the glacier and the rocks below it. The top of the cave was smooth and majestic blue, because a hint of light was coming through the ice from the sun. We all crawled out of the cave dripping with mud, but with thrilled smiles on our faces!

After lunch, we split off into our teams to check on experiments we had started on Wednesday. The GPS team remeasured the flag locations to see how much the glacier had moved in the past four days, and the stream team measured the speed and amount of water flowing down the different-sized surface streams. The stream team also took pictures of their streams to compare with other pictures they had taken earlier that week. This would tell us how much it changed over the time we were here. When everyone finished, we split off into new groups to figure out how much water was flowing in the many small streams on top of the glacier compared to those under the glacier. One group counted all the streams across the glacier and categorized them into three sets of streams: large, medium or small.

On the way back to the middle of the glacier, Cece led us up to see some larger crevasses. Along the way, we found ice worms that live on algae growing in the snow stuck in the crevasses' ice. Ice worms are but one part of the glacier's ecosystem; we also saw spiders, grasshoppers and other insects, as well as birds like the Rosy Finch that eat ice worms and the other bugs that hang out on the glacier.

The other group worked with Erin to measure the width and depth of small, medium and large streams and the velocity of their water flow. This was easier said than done. To measure velocity, the team had to drop a small object into the stream at a certain point, start a timer, and stop timing when it passed another point. We could not find an object that was fit for the job. We tried using a leaf, which got stuck on ice crystals on the bottom of the stream. Other natural debris was similarly frustrating. Then we used a pencil—that worked well, but only in a medium and large stream, and we had to make sure we didn't lose it downstream. But the small stream's water flow was very weak, with lots of ice crystals, making it difficult to get any object to move uninterrupted down the stream. Tiffany finally decided to "redesign" the stream by brutally chopping away at it with her ice ax. After a long struggle, the bottom of the stream was perfectly smooth. The team decided to use Tiffany's ChapStick cap, which was just perfect for the stream.

There is nothing more exciting than cramponing down the side of a glacier at breakneck speed after a mountain goat—otherwise known as Cece! Most of us followed her and Erin to further explore the glacier. Sarah Fortner, another one of our instructors, who was from Ohio State University, led another crew back to camp to identify more alpine plants and learn their tricks for living in a cold, exposed environment. Nine pairs of crampons echoed throughout the glacial valley. We hiked through crevasses covered in mud and rocks. We crossed a particularly tricky crevasse, and Cece connected a rope to our harnesses to help us safely climb through the crevasse.

We began to head up the mountain farther after an hour of exploring the lower glacier. We took a rather circuitous route upslope because many crevasses were hiding under the snow patches. This became quite annoying, so we decided to rope up a more direct route using our harnesses. We traversed up and then across the glacier to pick up all of our old marker flags from a hike in the fog two days earlier.

Once off the glacier, we took off our crampons and headed up to the Metcalfe Moraine, constantly glancing back at the gorgeous glacier we came to know. At the top of the moraine was the very first place we had seen our glacier. We could see our camp 50 feet below on the other side of the moraine, and we waved to Sarah, Sabrina and Cate, hoping this would spur them to begin boiling water for dinner. Then we began our decent and, 20 minutes later, arrived at our delightful little habitat.

That evening, our conversation was often interrupted by gasps when we saw amazing meteorites shooting across the sky. We were lucky to be up there for the Perseid meteor shower. Most girls slept in their tents, but Brittney, Diana, Tiffany and Kelsi stayed outside with Erin and Cece. They wanted to watch the shooting stars as they fell asleep. It was amazing.