The Gory Details of Artist Katrina van Grouw’s Unfeathered Birds

A British artist, with experience in ornithology, explains how she created anatomical drawings of 200 different species of birds for a new book

![]()

Katrina van Grouw’s new book The Unfeathered Bird is a work of passion. A former curator in the ornithological division of London’s Natural History Museum, the fine artist, based in Buckinghamshire, England, has used her experience in ornithology and taxidermy to draw, over the course of her career, 385 beautiful illustrations of birds—all, as the book’s title suggests, without their feathers. Her work shows the skeletal and muscular systems of 200 different species, from ostriches to hummingbirds, parrots to penguins, in life-like poses.

Collage of Arts and Sciences interviewed van Grouw by email.

When did you draw your very first bird illustration for this book?

Twenty five years ago! But it was a couple more years before the idea for the book became a burning ambition. I was an undergraduate fine art student with a passion for natural history, and I wanted to produce a set of anatomical drawings as background research for my images of living birds. I found a freshly dead mallard washed up on the beach and began stripping off each layer of muscle, before boiling up and reassembling the skeleton. I drew everything from several angles. It took months! I decided—if you’re going to spend several months intimately involved with a dead duck, it’s got to have a name. So, I christened her Amy. Her skeleton still stands in a glass case in my living room, and the book is dedicated to her.

What have you done in your illustrations of birds that hasn’t been done before?

Several things, in fact. Of course, I’m not the first person to draw skeletons. There are some utterly gorgeous anatomical illustrations from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. At this time however, natural history was preoccupied with taxonomy, and the emphasis was on showing obscure features that were thought to reveal evolutionary relationships. If whole skeletons were pictured at all, they would probably have been drawn from specimens mounted in static and inaccurate postures.

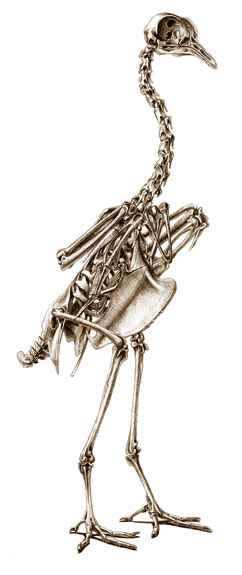

What I wanted to do was combine the aesthetic beauty typical of these historical images with information about living birds—their behavior and lifestyle. I wanted to focus on the effects of convergent evolution, or how different bird groups have adapted to similar niches. The skeletons in The Unfeathered Bird are shown flying, swimming, feeding—each in the way typical for that group.

What museum collections did you work from?

I used museums for many of the drawings of individual skulls and for skeletons of the species that I wasn’t able to obtain freshly dead. I’m indebted to the many curators and collections managers who allowed me to use their research collections, issued loans or sent photographs. (I only used photographs in conjunction with actual specimens, but they were nevertheless very useful.) Most articulated museum specimens, however, are not in a reliably lifelike position, and certainly not in active or characteristic poses. For that, we’d have to prepare our own.

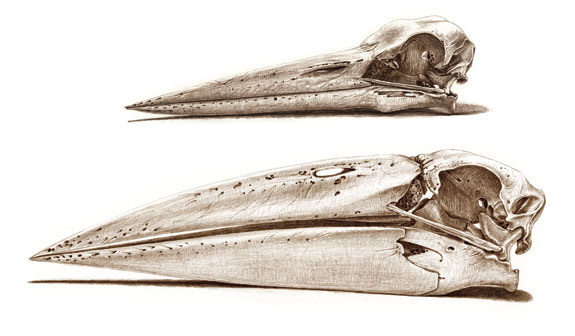

Skulls of a European White Stork, (Ciconia ciconia), at top, and a Marabou (Leptoptilos crumeniferus), at bottom. © Katrina van Grouw.

When you collected your own specimens, where did you collect them, and how did you prepare them?

No birds were harmed in the making of the book. We approached aviculturists, taxidermists and conservation charities and received, as donations or on loan, a large quantity of birds that had died of natural causes. This way, we could prepare the skeletons at home in the required position. I say “we” but my husband, Hein, did all the work. (Hein, too, is a museum curator and ornithologist, with many years’ experience in preparing bird specimens.) He prepared most by boiling, then would clean and reconstruct the skeleton in whatever position I dictated. Actually, we discussed each at length and usually arrived at a decision we’d be mutually happy with! Our tiny house was soon completely taken over with skeletons in various stages of preparation—from pans boiling on the kitchen stove to toucans in the sink, and penguins in the bath!

How did you keep the skeletons in position?

Once they were re-assembled, with a wire through the vertebrae and all the other bones either wired or glued in place, Hein’s skeletons are as robust as any museum specimen. Drawing the musculature of skinned birds as though they were alive, however, was much more difficult. Sometimes I’d rig up the carcasses on a Heath Robinson-esque maze of wires, pins, thread and blocks of wood to make a faintly grotesque artist’s mannequin. Otherwise, I’d just sit with the bloody carcass draped over my lap and use references of living birds to re-animate it directly on the drawing.

How did you determine which species to include?

It was more difficult to decide which species not to include! I could happily have gone on adding drawings forever. The more I researched, the more I discovered things I felt I simply had to put in.

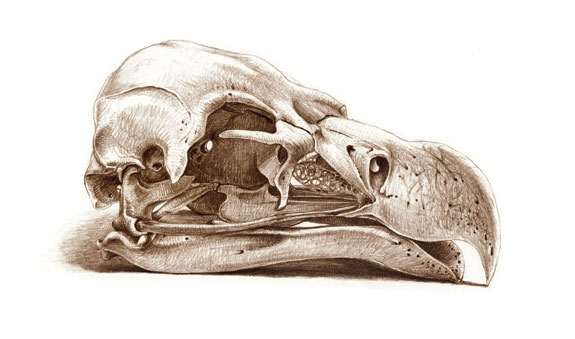

I tried to cover as many of the traditional groups as possible, with at least one bird shown as a complete skeleton and sometimes additional drawings showing the musculature or feather tracts of the whole bird. Extra drawings of skulls, feet, tongues, windpipes and other bits and pieces were included to show variation or adaptations of particular interest.

What types of information did you want your drawings to convey to viewers?

When I first had the idea for the book I’d intended it to be aimed primarily at artists and illustrators. Therefore, I wanted to focus on the way a bird’s anatomy affects its outward appearance—what’s actually going on underneath the feathers when a bird is moving. It was only afterwards that I realized that it would have wider appeal.

It might be easier to say what I didn’t want, and that can be summed up in two words: annotated diagrams. If you want to know the names of individual bones, look in a textbook! For The Unfeathered Bird I felt it would only clutter up the images and, worse still, make readers feel obliged to read and learn them. My aim was to convey general principles about the way birds are adapted to their lifestyle.

Some people might be surprised to find the arrangement of chapters based around Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae. There were several reasons for this, but it was chiefly so that I could compare similar adaptations in unrelated birds, whilst still following a recognized (albeit antiquated) scientific order.

About how long did you spend on each drawing?

The more practiced I am, the faster I get, or, more accurately, the better the eye-hand coordination with fewer rubbings out! But on average, a skull will take an hour or two and a whole skeleton may take up to a week, or even longer. Backache, neck ache, eye-fatigue and sore fingers are the things that slow me down.

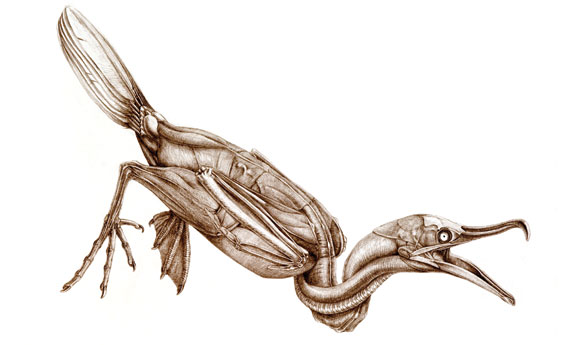

Magnificent Frigatebird (Fregata magnificens), at right, with White-tailed Tropicbird (Phaethon lepturus), at left. © Katrina van Grouw.

What specimen presented the most challenges? And why?

Without a doubt, the greatest challenge was drawing lifelike skeletons from bones that were not articulated at all—the ones in scientific reference collections in natural history museums. As a former bird curator at Britain’s Natural History Museum, I know that the people using skeleton collections—mostly zooarchaeologists—need to study the articulating surfaces of individual bones, so they’re not much use if they’re glued or wired together. However, this makes it quite difficult for artists!

I worked out a clever solution: I would draw the skeleton of another bird already prepared in the position I wanted, then rub out and re-draw each bone in turn, with reference to the respective bone of the desired species. It works remarkably well.

Probably my favorite picture in the book, the Magnificent Frigatebird, was drawn in this way, from a disarticulated skeleton loaned to me by the Field Museum, Chicago, modelled from the position of the tropicbird it’s chasing. I’m a huge fan of both frigatebirds and tropicbirds (with feathers on), so it was important for me to get it right, and do justice to the dynamism and excitement of a real-live aerial pursuit.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)