The Insane Amount of Biodiversity in One Cubic Foot

David Liittschwager travels to the world’s richest ecosystems, photographing all the critters that pass through his “biocube” in 24 hours

![]()

When one sets out to document the diversity of life on Earth, there’s a real advantage to limiting the sample size.

“I thought one cubic foot would be manageable,” says David Liittschwager, sitting behind the wide, unadorned work table that fills the dining room of his San Francisco flat. Framed images of some of the thousands of animals and plants he’s photographed during the past 25 years hang on the walls. “A cubic foot fits in your lap; you can put your arms around it. If you stand with both feet together and look down, it’s just about the size of your footprint while standing still,” he says. “I thought it was something I could actually get through, and finish.”

Common Name: River Cooter, Scientific Name: Pseudemys concinna, 4″ across carapace, Location: Lillard’s Mill, Duck River, Milltown, Tennessee. © David Liittschwager.

For the past five years, Liittschwager—a quiet perfectionist who served as an assistant to both Richard Avedon and Mary Ellen Mark, and now works with both the Smithsonian and National Geographic—traveled the world with a three-dimensional stainless steel frame, exactly one cubic foot in volume.

His notion was simple and thrilling: to place the lattice in some of the planet’s richest ecosystems and see how many organisms occupy or pass through that relatively small (if you’re a squirrel) or huge (if you’re a diatom) parcel of real estate in 24 hours.

The numbers turned out to be pretty big.

The six locations Liittschwager chose were a bucket list of dream journeys; from a coral reef in Moorea, French Polynesia, to a fig branch high in the cloud forest of Costa Rica. The cube was submerged in Tennessee’s Duck River (“the most biologically diverse river in the United States,” Liittschwager assures me) and a nature sanctuary in Manhattan’s Central Park. The fifth stop was a burnt patch of fynbos (shrub land) in Table Mountain National Park, in South Africa. Finally, the well-traveled cube returned home to dredge the currents beneath the Golden Gate Bridge.

In each case, Liittschwager and his teams encountered myriad beings—from about 530 in the cloud forest to more than 9,000 in every cubic foot of the San Francisco Bay.

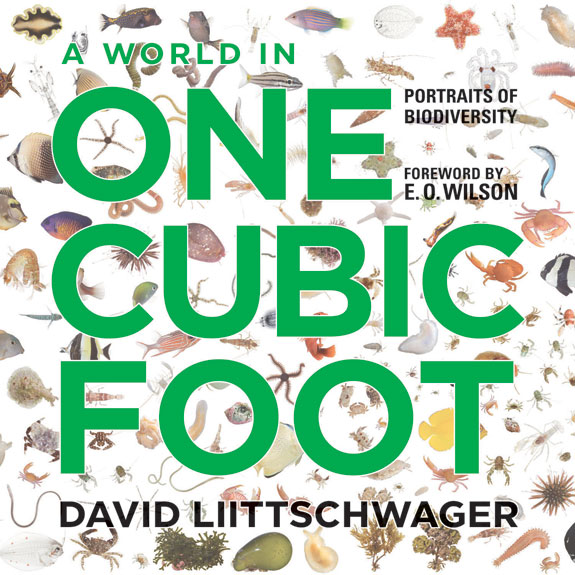

The results appear in Liittschwager’s new book, A World in One Cubic Foot: Portraits of Biodiversity (University of Chicago Press). Like his previous works—which include Witness: Endangered Species of North America (1994) and Skulls (2002)—these images are frank, revealing and unassumingly poetic. Printed on plain white backgrounds, the animal portraits recall Avedon’s “In the American West” series, which Liittschwager helped print in the mid-1980s.

Liittschwager placed a cube in the Hallett Nature Sanctuary, a four-acre preserve in Manhattan’s Central Park. © David Liittschwager.

One surprise is how odd and tiny so many of the creatures turn out to be. “Most of the world’s biodiversity is small, cryptic things,” Liittschwager confirms. “Things that hide in cracks and underneath and on the backside of the things that we see.”

Lots of people photograph plants and animals. But no one does it more painstakingly, or with greater compassion, than Liittschwager. His gift is instantly apparent. Though dozens of the creatures documented in A World in One Cubic Foot are totally foreign to our experience, Liittschwager creates an intimacy that you feel in your gut.

Common Name: Eastern Gray Squirrel, Scientific Name: Sciurus carolinensis, Size: 7.09″ body length, Location: Hallett Nature Sanctuary, Central Park, New York. © David Liittschwager.

“I don’t find myself, or a deer, any more magnificently made than a beetle or a shrimp,” says the photographer. His work supports the claim. One can’t look at these images without being in awe of these creatures, and feeling empathy for their well being. Liittschwager reveals his subjects’ innate nobility—whether it’s a bush tanager from Costa Rica, a Polynesian squat lobster or a Central Park midge.

The photographer also monitored a cubic foot in the fynbos (shrub land) in South Africa’s Table Mountain National Park. © David Liittschwager.

“Does it take more patience,” I ask, “to photograph animals than it did to photograph people with Avedon?”

“It does,” Liittschwager nods. “The work Richard did in portraiture did not take very long. He would see somebody that he wanted to photograph, and then it could be a five- to ten-minute session in front of a simple background. To chase a running insect around a petri dish for an hour, trying to get it in the frame and in focus, is not uncommon.”

Any project that blends art and science will involve some guesswork and—well—“unnatural” selection. The Central Park chapter includes a portrait of a raccoon. “It was sleeping on the tree, right above us,” says Liittschwager. “We didn’t actually see the raccoon, but one day the cube had been moved—and the raccoon was the only thing big enough to do it!”

Common Name: Jewel Scarab, Scientific Name: Chrysina resplendens, Size: 3.1 cm body length, Location: Monteverde Cloud Forest Biological Reserve, Costa Rica. © David Liittschwager.

Likewise the jewel scarab: an aptly-named Costa Rican beetle. “They’re really strong fliers but kind of clumsy,” notes Liittschwager. “This guy was just flying along in the cloud forest canopy, 90 feet up in a tree. He whacked into my head—and fell into the cube.”

Right now Liittschwager is in Belize, working with the Smithsonian on a related art/science exhibition about these “biocubes.” It’s slated to open in 2014 at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. “We’re working together to digitize diversity, one cube at a time,” says research zoologist Chris Meyer, who has been collaborating with Liittschwager for about four years. “David gets the shot, and I get a genetic fingerprint for each species. So while David puts ‘faces to names,’ my job is to put ‘names to faces.’ ”

So what’s the take-away lesson from a work like this?

“That even small spots matter,” Liittschwager says without hesitation. “And that there is no small spot that’s not connected to the place right next to it. There’s nothing that’s separate.”

The photographer’s view is reflected in the book’s six essays—one for each biosphere—and in the foreword by E.O. Wilson. In his own introduction, Liittschawager quotes Wilson: “A lifetime can be spent in a Magellanic voyage around the trunk of a single tree.”

Which makes it, Liittschwager observes, too big a sample size.

Guest blogger Jeff Greenwald is a frequent contributor to Smithsonian.com.