The Jaguar Freeway

A bold plan for wildlife corridors that connect populations from Mexico to Argentina could mean the big cat’s salvation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Jaguars-female-walking-631.jpg)

The pounding on my door jolts me awake. “Get up!” a voice booms. “They caught a jaguar!”

It’s 2 a.m. I stumble into my clothes, grab my gear and slip into the full-moon-lit night. Within minutes, I’m in a boat with three biologists blasting up the wide Cuiabá River in southwestern Brazil’s vast Pantanal wetlands, the boatman pushing the 115-horsepower engine full throttle. We disembark, climb into a pickup truck and bump through scrubby pastureland.

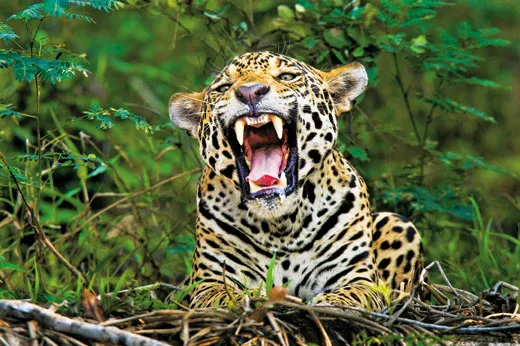

Half a mile in we see them: two Brazilian biologists and a veterinarian are kneeling in a semicircle, their headlamps spotlighting a tranquilized jaguar. It’s a young male, about 4 years old: He’s not fully grown and the dagger-like, two-inch canines that protrude from his slack jaw are pearly white and show no signs of wear.

A device clipped to his tongue monitors heart rate and respiration. Under the sedative, the cat stares open-eyed, having lost his blink reflex. Joares May, the veterinarian, dons surgical gloves, puts salve in the jaguar’s eyes and shields them with a bandanna. He draws blood and urine, collects fur for DNA studies and pulls off ticks that he will scan for diseases. Three members of the research team affix a black rubber collar around the cat’s neck. It’s fitted with a satellite transmitter that—if all goes well—will send four GPS locations daily for the next two years, allowing the team to track the cat’s movements.

It takes five men to heft the cat onto a scale: He weighs 203 pounds. They measure his length, girth, tail and skull. He bears evidence of fighting, probably battling another male over territory. May dabs salve on half-healed cuts covering the cat’s massive head and paws. He’s also missing half an ear. The team nicknames him “Holyfield,” after Evander Holyfield, the boxer who lost a portion of his ear to Mike Tyson’s teeth in 1997; certainly the jaguar’s compact, muscular body radiates the power of a prizefighter. Officially, the animal will be designated M7272.

In dozens of trips into the green heart of Central America’s rain forests over 20-plus years, I’d never even glimpsed a jaguar. I am stunned by the majesty of this animal. His rosette-spotted coat is exquisite. Alan Rabinowitz, the world’s foremost jaguar expert, stands beside me. “What a beauty,” he says.

The vet completes his tests and still Holyfield hasn’t stirred. We take turns crouching beside him, posing for snapshots. There is nothing like being this close to a sleeping jaguar, breathing in his musky scent, stroking his smooth fur. But taking these pictures feels somehow wrong, reminiscent of trophy photos.

The jaguar blinks. It’s time to go. The vet and a biologist stay behind to watch over him until he wakes completely and stumbles off. We motor back to our lodgings as feeble, predawn light pales the sky.

The jaguar, Panthera onca, also called el tigre, is the largest cat in the Western Hemisphere and the third largest in the world, after the tiger and lion. It has been a symbol of power across the Americas, woven into culture and religion at least as far back as the Olmec civilization in 1150 B.C.; the Olmecs depicted half-human, half-jaguar figures in their art. The Maya associated jaguars with warfare and the afterlife; modern Mayan shamans are thought to be able to take on a jaguar’s form. In 15th-century Bolivia, Moxos Indian priests were initiated by battling a jaguar until wounded by the cat, considered an embodied god. The Aztec emperor Montezuma was draped in jaguar skins when he went to war; conquered enemies gave jaguar pelts in tribute.

In antiquity, killing a jaguar was often part of a religious ceremony or a mark of status. But as ranches and settlements sprang up across Latin America, jaguars lost their religious significance. Demonized as dangerous predators, they were routinely shot. The fashion craze for fur after World War II added to the carnage; in 1969 alone, the United States imported nearly 10,000 jaguar pelts. Only a 1973 international ban stemmed the trade. Killing jaguars is now illegal throughout their range, but enforcement is minimal, and the cats have been wiped out in El Salvador and Uruguay. Meanwhile, over the past century people have razed or developed 39 percent of jaguars’ original habitat across Central and South America.

Rabinowitz began studying jaguars in the early 1980s. He lived among the Maya in the forests of Belize for two years, capturing, collaring and tracking the animals for the New York Zoological Society (now known as the Wildlife Conservation Society). Many of the jaguars Rabinowitz studied were shot by locals. He also encountered black-market traders, one with 50 jaguar skins. “It didn’t take a brain surgeon to see the writing on the wall,” he says. He couldn’t just gather data and watch the slaughter. He lobbied government officials to create a protected area for the cats, and in 1984, Belize’s Cockscomb Basin became the world’s first jaguar preserve. Now encompassing about 200 square miles, it is part of the largest contiguous forest in Central America. Jaguars are now thriving in Belize, where ecotourism has made them more valuable alive than dead.

But Rabinowitz despaired over the animals’ decline elsewhere. And he worried that jaguars in the Cockscomb Basin and other isolated preserves would become inbred over time, making them weak and susceptible to hereditary disease. So he conceived a grand new conservation strategy to link up all the populations in the Americas. Once linked, members of different jaguar populations could, in theory, roam safely between areas, breed with one another, maintain genetic diversity—and improve their survival odds.

“Saving a wide-ranging mammal species throughout its entire range has never been attempted before,” says Rabinowitz, who is CEO of Panthera, a wild cat conservation organization founded in 2006 by New York entrepreneur Thomas Kaplan. Panthera’s staff includes George Schaller, widely considered the world’s pre-eminent field biologist. In the 1970s, Schaller and Howard Quigley, who now directs Panthera’s jaguar program, launched the world’s first comprehensive jaguar study.

Panthera’s Jaguar Corridor Initiative aims to connect 90 distinct jaguar populations across the Americas. It stems from an unexpected discovery. For 60 years, biologists had thought there were eight distinct subspecies of jaguar, including the Peruvian jaguar, Central American jaguar and Goldman’s jaguar. But when the Laboratory of Genomic Diversity in Frederick, Maryland, part of the National Institutes of Health, analyzed jaguar DNA from blood and tissue samples collected throughout the Americas, researchers determined that no jaguar group had split off into a true subspecies. From Mexico’s deserts to the dry Pampas of northern Argentina, jaguars had been breeding with each other, wandering great distances to do so, even swimming across the Panama Canal. “The results were so shocking that we thought it was a mistake,” Rabinowitz says.

Panthera has identified 182 potential jaguar corridors covering nearly a million square miles, spanning 18 nations and two continents. So far, Mexico, Central America and Colombia have signed on to the initiative. Negotiating agreements with the rest of South America is next. Creating this jaguar genetic highway will be easier in some places than others. From the Amazon north, the continent is an emerald matrix of jaguar habitats that can be easily linked. But parts of Central America are utterly deforested. And a link in Colombia crosses one of Latin America’s most dangerous drug routes.

A solitary animal that leaves its birthplace in adolescence to establish its own territory, a jaguar requires up to 100 square miles with sufficient prey to survive. But jaguars can move through any landscape that offers enough fresh water and some cover—forests, of course, but also ranches, plantations, citrus groves and village gardens. They travel mostly at night.

The pasture where Holyfield was collared that night in Brazil’s Pantanal is part of two “conservation ranches” overseen by Panthera with Kaplan’s financial support. The ranches straddle two preserves, making them an important link in the corridor chain and together creating 1,500 square miles of protected habitat. On an adjacent property, Holyfield might have been shot on sight as a potential cattle-killer. But not here.

These ranches are expected to be more successful than others by using modern husbandry and veterinary techniques, such as vaccinating cattle herds. Because disease and malnutrition are among the leading killers of cattle in this region, preventing those problems more than makes up for the occasional animal felled by a jaguar.

“My vision was to ranch by example,” Kaplan says, “to create ranches that are more productive and profitable and yet are truly jaguar-friendly.”

As a child growing up near Fort Lauderdale, Florida, Kaplan read an article about tigers written by Schaller, then of the New York Zoological Society, which inspired his interest in cat conservation. Kaplan went on to track bobcats near his home, and he dreamed of becoming a cat biologist. Instead, he got a PhD in history from Oxford University and became an entrepreneur, earning a fortune in gold, silver, platinum and natural gas. Kaplan was intrigued by Rabinowitz’s book Jaguar and says Rabinowitz “followed the life path that I would have if I were a less acquisitive person.”

Fortified by a windfall from a silver-mine investment, Kaplan took a step down that path in 2002 by contacting Rabinowitz. The two men bonded over their desire to save big cats, although it was an unlikely mission for both of them. “Alan is allergic to cats,” Kaplan says, “and I’m a vegetarian—funding ranches with 8,000 head of cattle.”

Late one afternoon, I took a boat up the Cuiabá River with Rafael Hoogesteijn, Panthera’s expert on livestock depredation. It was the end of the dry season, the best time of year to see jaguars. Soon, months of rain would swell the Paraguay River and its tributaries, including the Cuiabá. Their waters would rise by up to 15 feet, backing up like a plugged bathtub and inundating 80 percent of the Pantanal flood plain. Only a few areas of high ground would remain above water.

The Pantanal’s immense freshwater wetlands are the world’s largest, covering almost 60,000 square miles, about 20 times the size of the Florida Everglades. Bulldog-size rodents called capybara watched us, motionless, from the shallows. A lone howler monkey lay in a tree, back legs swinging in the breeze. Caiman submerged as we passed. A six-foot anaconda coiled under a tree. Innumerable birds took flight as we floated by: kingfishers, eagles, cotton-candy-colored spoonbills, squawking parrots, stilt-legged water birds. Jabiru storks with nine-foot wingspans glided overhead.

With abundant prey, the cats here grow to be the largest in all of jaguardom. One male collared in 2008 weighed 326 pounds, about three times more than an average Central American jaguar. The Pantanal ecosystem nurtures perhaps the highest density of jaguars anywhere.

Our boatman veered off into a small creek, navigating low, coffee-colored waters choked with water hyacinth. Fish jumped, glinting, in our wake. A stray piranha landed in the boat, flopping at our feet. We rounded an oxbow and startled a tapir that swam wild-eyed for shore, holding its prehensile, elephantine trunk in the air.

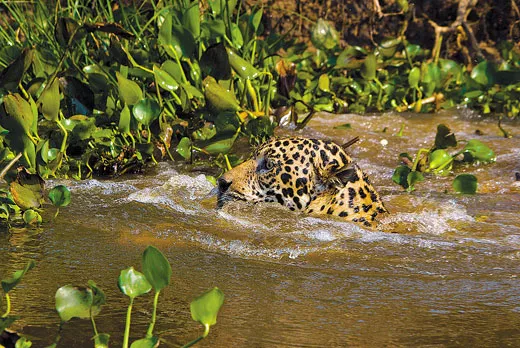

On a sandy beach we spied jaguar tracks that led to a fresh kill. The boatman pulled close. A few scraps remained of a six-foot caiman carcass. Hoogesteijn pointed out the cat’s signature, a crushing bite to the skull, so different from the strangling throat-hold used by lions and tigers. This may be the source of the jaguar’s name, derived from the Tupí-Guaraní word yaguareté, meaning “beast that kills its prey with a single bound.”

Jaguars have the most powerful jaws of any cat, strong enough to crack sea turtle shells. Though they prefer large prey, they’ll eat almost anything—deer, capybara, frogs, monkeys, birds, anacondas, livestock. Jaguars rarely kill people, although they have done so, usually when cornered in a hunt.

A few nights later, we witnessed an adult jaguar silently stalking something in the shallows. It dived, and when it surfaced, a four-foot caiman dangled from its mouth. This amazed the biologists—they didn’t know jaguars hunted with such stealth in water. Much remains to be learned about jaguar behavior.

The Pantanal has been the scene of jaguar-cattle conflict ever since cows were introduced by the early 18th century. Many ranches once employed an onçeiro, a jaguar hunter. It was a position of honor, and Joaquim Proença, now Panthera’s ranch manager, was among the best. He thinks he must have killed 100. In the traditional way, he and a posse tracked a jaguar with a pack of pedigreed hounds, following on horseback until the hounds treed or surrounded the cat. “It was more dangerous when the cat was on the ground, but more manly,” says Proença. “You needed a perfect shot.” When he went to work for Panthera, he sold his hounds and stopped hunting. But the locals still tease him. They say he has lost courage—he’s no longer a man.

Ninety-five percent of the Pantanal’s land is privately owned, with some 2,500 ranches running nearly eight million head of cattle. In a survey, 90 percent of ranchers said they considered jaguars part of their heritage, yet fully half also said they wouldn’t tolerate the cats on their property.

Under Hoogesteijn’s supervision, the conservation ranches are testing various ways to protect livestock. One measure is to graze water buffalo among cattle. Cows tend to stampede when a jaguar comes near, leaving calves vulnerable. “For jaguars, it’s like going to Burger King,” Hoogesteijn says. Water buffalo encircle their young and charge intruders. Panthera is testing water buffalo in the Pantanal and will expand the test herds to Colombia and Central America next year. Another Panthera experiment will reintroduce long-horned Pantaneiro cattle, a feisty Andalusian breed brought to South America centuries ago by the Spanish and Portuguese. Like water buffalo, these cattle defend their young.

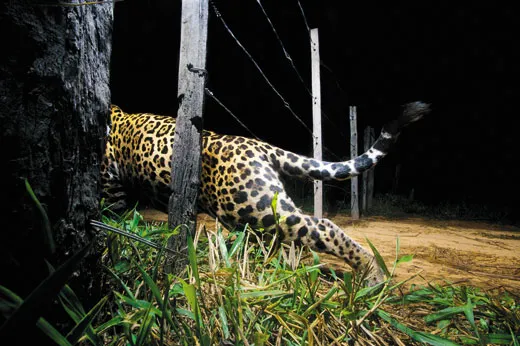

Because jaguars tend to approach cattle under cover of forest, some Pantanal ranchers corral their pregnant females and newborns at night in open, lighted fields surrounded with electric fences packing 5,000 volts—strong enough to discourage even the hungriest cat.

To figure out where the corridors should be, Rabinowitz and other biologists identified all the so-called “jaguar conservation units” where breeding populations of the cats live. Kathy Zeller, a Panthera landscape ecologist, mapped pathways linking the populations, taking into account proximity to water, distance from roads and urban settlements (jaguars shy away from people), elevation (under 3,000 feet is best) and vegetation (cats avoid large open areas). Out of 182 possible corridors, 44 are less than six miles wide and are considered at risk of being lost. Panthera is securing the most fragile tendrils first. “There are places where if you lose one corridor, that’s it,” she says. Researchers are now checking out the pathways, interviewing locals, tracking collared cats and ascertaining the presence—or absence—of jaguars.

Rabinowitz has met with government leaders about drawing up zoning guidelines to protect corridors. “We’re not asking them to throw people off their property or create new national parks,” he says. The goal is not to halt development, but to influence the scale and placement of mammoth projects like dams or highways. The strategy has worked on a smaller scale for cougars in California and grizzly bears in the western United States.

In April 2009, Costa Rica incorporated the Barbilla Jaguar Corridor into its existing wildlife corridor system. Panthera regards the initiative as a possible model for the Americas. It’s overseen by a 25-person Costa Rican corridor committee of ecotourism operators, indigenous leaders, cowboys, cilantro farmers, villagers, businessmen, university researchers and others. They helped identify an imminent threat: a hydroelectric project on Reventazón River that would bisect the Barbilla corridor and block the passage of jaguars. With advice from Panthera, Costa Rica’s electricity utility is considering creating a buffer zone by buying adjacent forest and reforesting along the reservoir’s edge to keep a pathway intact.

Perhaps the most critical link runs through Colombia, where only a few Andean passes are low enough for cats to cross. Losing this corridor would split the trans-American population in two, and the jaguars on either side would no longer interbreed.

The region is as important to the illegal cocaine trade as it is to jaguars. Last fall, Panthera’s researchers in Colombia were setting up camera traps when a killing spree in their hotel and on a nearby road left four people dead. There are ongoing battles among guerrilla and criminal groups for control of cocaine fields and trafficking routes. Targeted kidnappings and murder are commonplace, and the landscape is riddled with land mines. It’s nearly impossible for biologists to study jaguars here, or protect them.

There are challenges all along the jaguars’ range. Sinaloa, Mexico, is a haven for Mexican crime bosses. A notorious gang, known as MS-13, rules parts of El Salvador and is spreading throughout Central America. Huge soybean and sugar cane plantations are denuding the Brazilian Cerrado, a dry grassland, washing pesticides down into Pantanal rivers and potentially severing the route to the Amazon. Then there’s the proposed eight-lane highway that would run from Honduras to El Salvador, linking Pacific and Caribbean ports. “I can almost guarantee you that it’ll stop the passage of jaguars, just like the fence that we’re building along the southern U.S. border,” says Panthera’s Quigley. There hasn’t been a breeding population in the United States in 50 years, but at least four jaguars were spotted in Arizona and New Mexico in recent years. Only one jaguar has been seen in Arizona since the fence was erected.

Still, he adds, roads can be made less deadly by limiting the number of lanes and incorporating wildlife-friendly underpasses like those used in Florida to protect panthers and other wildlife.

Rabinowitz is encouraged that in some places, jaguars are gaining support. In Belize, where jaguars serve increasingly as an attraction for ecotourists, Maya who once killed the animals are now their protectors. “It’s not born-again enlightenment,” says Rabinowitz. “It’s economics.” Jaguar tourism is also bringing money into the Pantanal. Carmindo Aleixo Da Costa, a 63-year-old rancher, says that hosting a few foreign tourists doubles his annual income. “Now is the time of the jaguar!” he says, beaming.

Ultimately, studies of DNA from jaguars throughout their range will determine whether or not the corridor project will enable populations to interbreed with other populations. George Amato, of the American Museum of Natural History in New York, directs the world’s largest cat genetics program; the museum’s freezers hold more than 600 DNA samples from around 100 different jaguars, and Panthera regularly sends Amato new samples of jaguar scat. “In five years we’ll know every jaguar by name,” he jokes.

Near sunset, I join the team and we head upriver in three boats, scouring small creeks in the fading light. Our boatman scans the shoreline with a powerful spotlight. The beam swarms with insects and the frenetic flights of fish-eating bats. Along the shore, the orange glints of hundreds of pairs of caiman eyes shine brightly, like runway reflectors on a landing strip, guiding us back toward the lodge under a swollen moon.

A few miles from one of Panthera’s conservation ranches, we spot a male jaguar lying on a beach. He seems unconcerned by our presence. He yawns, rests his head on his paws, then slowly, luxuriously, grooms himself like a massive housecat. When he’s finished, he rises, stretches and saunters off into the brush.

A mile on, another good-sized animal swims by us. The boatman points. “Onça,” he whispers, Portuguese for jaguar. It bounds onto the bank, water flying as it shakes. It’s a female. She lopes off into the head-high grasses like a spotted apparition. We kill the engine and wait for another glimpse. She reappears, leaping effortlessly onto a high rock.

Two nights later, the biologists trap and collar a young female. We wonder if it’s the cat we’d seen. This one, F7271, is nicknamed “Espada” for a spade-shaped marking on her side.

The two young collared cats—Holyfield and Espada—represent precisely the demographic the jaguar corridor is designed for: the young and mobile.

The collars will later reveal that Espada traveled 85 miles in 76 days, staying mostly on one of the conservation ranches and within the adjacent state park. Her territory overlapped with Holyfield’s, who traveled 111 miles in 46 days.

The key to the success of the corridor project, says Quigley, “is that we’re not starting too late.” Unlike other species in the Panthera genus, such as tigers and snow leopards, jaguars may escape the endangered species list.

“Fortunately,” adds Kaplan, “a sufficient amount of land and political will exists that the jaguar really has a fighting chance.”

Sharon Guynup is a writer in Hoboken, New Jersey, who specializes in science, health and the environment. Conservation photographer Steve Winter works for Panthera.