The Komodo Dragon is an All-Purpose Killing Machine

A visit to one of Indonesia’s most popular tourist destinations could be your last

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/The-Dragon-King-Komodo-Dragon-631.jpg)

It didn’t seem prudent to bring two small children along. We had just docked at a remote island in southeastern Indonesia, and the five-hour hike would traverse a rocky, exposed ridge in the baking heat of the dry season. My companions—a blond Frenchman named Fred, his wife and their two kids—were dressed for a game of shuffleboard. My concern heightened when I saw he had a single water bottle for the four of them. Also, there were dragons.

“Are you sure you want to do this?” I asked Fred, glancing at his sockless feet and leather loafers. We had just met at the tourist dock on Flores the day before.

“You are the one who proposed it,” he said, marching onward.

True. I’d come to Indonesia on my own for a month, and I wasn’t about to miss this opportunity. Komodo Island and its nine-foot-long monitor lizard, the Komodo dragon, were once about as far off the beaten track as you could get. But Komodo National Park has become Indonesia’s hottest tourist spot this side of Bali. Our starting point in Labuan Bajo, on the island of Flores, was packed with hip cafés, hostels and diving shops. Cruise companies offer a two-day expedition to parkland on Komodo and Rinca islands. Komodo, about five times the size of Manhattan, got a makeover in the late 1990s, when the Indonesian government asked the Nature Conservancy and the World Bank to help it protect the island’s biodiversity, develop hiking trails and build a visitor center.

Even with these amenities, the destination’s popularity is surprising. Whale-watching may appeal to our spiritual side, while a glimpse of an orangutan or other primate cousin tugs at an evolutionary heartstring. The Komodo dragon, I believe, taps into our basic fears: a living incarnation of the fictional monsters that haunt our imaginations.

Our guide that August morning, Ishak, lifted his forked stick—a defense against snapping jaws—and we marched into the bush. Even the vegetation is reptilian: Crocodile trees with spiky bark sprout from volcanic soils, while Lontar palms tower over the upland savanna. After only a ten-minute walk we came to a gallery of tamarind trees shading a pit of mud and greenish scum. A female Komodo dragon was sprawled next to a tree, her black obsidian eyes unreadable. The beaded folds of her flesh hung from her neck and she had kicked her rear legs behind her with the insouciance that comes from being at the top of the food chain. Luckily, she was still digesting a meal from earlier that week—a small deer, according to Ishak—and in her postprandial stupor would probably not be pondering cuisine for another month.

Up ahead, however, I knew there were dragons in the brush, possibly hungry ones. At the top of a pass, a white cross commemorates Rudolf Von Reding Biberegg, an elderly Swiss tourist who vanished in 1974, presumably killed by a Komodo dragon. “He loved nature throughout his life,” the epitaph says.

***

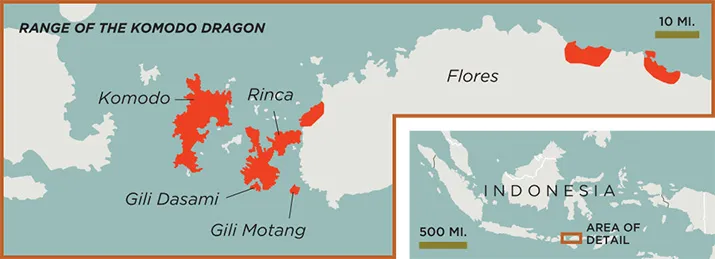

The Komodo dragon—the world’s largest lizard—first attained notoriety in the Western world following its discovery by Dutch colonial officials a century ago. Still, surprisingly few biologists have studied the creature in its natural habitat, which encompasses five islands in the Nusa Tenggara archipelago. Perhaps the most determined researcher was Walter Auffenberg of the Florida Museum of Natural History, who led an expedition to Komodo Island beginning in 1969. He needed three men to subdue some of the lizards, rodeo-style. They lassoed the Komodos, muzzled their snouts, tied their powerful legs together and blindfolded them to calm them down. Auffenberg weighed and measured the beasts and tagged them to keep track of their movements. The heaviest was 120 pounds, but a lizard with a full stomach can easily exceed 200 pounds.

Auffenberg spent more than a year on the island studying the dragon’s natural history—from its sunbathing habits to its courtship rituals—but he went out on a limb when he suggested that the dragons had evolved to their current size so they could hunt now-extinct pygmy elephants called Stegodons. In 1987, the U.S. scientist and author Jared Diamond lent his support to this theory, arguing that when the dragons’ smaller ancestors first arrived on Flores they had no carnivorous competitors and gradually grew larger to take advantage of such hulking prey.

In fact, scientists now say that the dragons evolved to full size on mainland Australia, where they had a lot of competition. In 2006, Scott Hocknull, a paleontologist at the Queensland Museum, discovered some puzzling fossils in a cave in northeastern Australia, and later confirmed that they were the remains of Komodo dragons that lived 3.8 million years ago. Rather than being the specialized product of island evolution, Hocknull argues, the dragon is really a “generalist carnivore” that feeds on multiple types of prey in a variety of environments. Relatives of the Komodo—monitor lizards that can grow five to six feet long—still live in Australia.

Auffenberg also popularized one of the biggest misconceptions about the Komodo—that its mouth is full of nasty bacteria that cause deadly lesions in bite wounds, enabling it to take down large prey, including water buffalo. He based the idea on bacteria he’d found in Komodo saliva and the infected wounds he’d observed in horses and water buffalo in western Flores.

“An enchanting fairy tale,” says Bryan Fry, a herpetologist at the University of Queensland. “It makes no evolutionary sense.” One problem is that water buffalo were introduced to the region by humans and have never been the dragon’s natural prey. Moreover, the dragons seldom succeed in killing such large animals. Fry says water buffaloes attacked by dragons develop infected wounds from wallowing in filthy water; if they die and become a dragon’s meal, that’s more of a lucky break (for the dragon, not the buffalo) than an evolutionary adaptation.

But there’s no denying the dragons are effective when they strike smaller prey, such as deer and pigs. Tim Jessop, a University of Melbourne ecologist, who has spent more time studying dragons in the field than anyone since Auffenberg, observed that 70 percent of the prey die within minutes, 20 percent die of blood loss within four hours and only 10 percent survive.

Why so lethal? Fry has discovered the secret is the mouth after all—dragons are venomous. When he scanned a dragon’s head with an MRI device, he found in its gums a series of glands that produce venom. It is secreted into the saliva and enters the wound created by the dragon’s sawlike teeth. This venom, Fry has shown, prevents blood clotting and causes muscles around blood vessels to relax, hastening blood loss and leading to a dangerous drop in blood pressure. “This is a sustained march toward unconsciousness,” says Fry.

At first glance, the discovery presents an evolutionary enigma. We usually think of venom, whether deployed by a rattlesnake or a scorpion, as a weapon that a small animal uses to kill larger prey, or to protect itself from becoming someone else’s meal. But the dragons aren’t exactly small. The answer, Fry realized after designing a computer model of the dragon’s jaw, was that the animal doesn’t have a strong bite. A saltwater crocodile, whose skull is about the same size, produces 6.5 times more bite force than a dragon. Komodos can barely hold onto prey, preferring to wound, release—and wait. “They grab whatever they can and slice it,” Fry says.

Previously, there were only two known venomous lizards: the Gila monster of the American Southwest and the Mexican beaded lizard. Their venoms lower blood pressure and impair coagulation, but also attack muscle tissue and disrupt the nervous system. Fry, having documented vestiges of venom glands in dozens of species, from Chinese crocodile lizards to seasnakes, concludes that the ability to produce venom emerged just once in the evolution of lizards and snakes 170 million years ago. If a species evolved another, perhaps more efficient means of subduing prey—like a rat snake’s constricting embrace—its venom glands atrophied over time, a phenomenon that biologists call a trait loss. The dragon evolved a slimmer skull—a precision cutting instrument—while retaining the venom. The result is a lethal dual-weapons system.

***

August is the height of the breeding season and, during our visit, most Komodo dragons were defending their nests or looking for mates far from established trails and water holes. Fred and his family were chipper as usual as we passed mounds of dirt and rock that were 10 to 20 feet in diameter and at least as tall as his 9-year-old son. The mounds are the nests of chicken-like birds called orange-footed megapodes, which don’t incubate their eggs with body heat but bury them atop plant matter that produces heat as it decays. The dragons remodel these nests for their own eggs, and guard them for six months, a rather long incubation.

Reptiles aren’t known for brains, but Komodo dragons create dummy chambers with dead ends, thwarting wild pigs and perhaps other, now-extinct scavengers—“the ghost of predation past,” says Jessop. When the dragons finally hatch, they take to the trees to avoid being eaten by larger dragons. At one point we spotted a tiny dragon that had risked a visit to the ground and was hunting for insects in the leaf litter.

By noon, we were out of the forest and had crested the ridge, gazing out across golden meadows and aquamarine waters that could have easily been mistaken for a southern California scene. We then trotted down the mountain. I slipped three times—unlike Fred’s 6-year-old daughter, who held out her arms like she was flying and didn’t trip once on the crumbling slope. When we got to the bottom and arrived at the last stop on the hike, Loh Sebita camp, we saw our last dragon, a somewhat pathetic creature lounging next to a wooden building on stilts, the kitchen. “If the dragon can’t hunt, he might come here,” Ishak says. “Sometimes the cook may throw out a chicken bone.”

The Komodo dragon is an endangered species, with an estimated 3,000 remaining in the wild. Conservationists say the animals have the most restricted geographic range of any large predator, and that poses a risk because a volcanic eruption or an islandwide fire could prove devastating. Jessop says the populations remain stable and healthy on Komodo and Rinca islands, but the numbers are falling on the smaller islands. On Flores, which is heavily developed and lies outside the national park, fewer than 100 dragons eke out a tenuous existence, and people (illegally) poison them to protect their goats. A small local organization, the Komodo Survival Program, was founded by one of Jessop’s Indonesian collaborators. But most of the support comes from park entry fees and businesses catering to dragon tourism.

Komodo dragons may not rank up with panda bears on the cuteness scale, but they have undoubtedly become a flagship species that has helped convince locals and visitors to embrace conservation in Indonesia.

The dragon is “a creature of imagination and fantasy,” says Fry. Except it’s real. And, he adds, “You are able to get up to it very, very close.”