The New World’s Oldest Calendar

Research at a 4,200-year-old temple in Peru yields clues to an ancient people who may have clocked the heavens

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/digs_ruins_388.jpg)

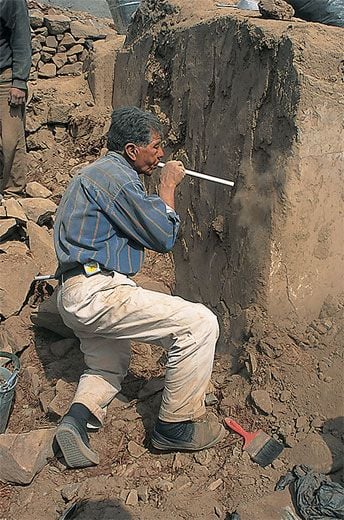

They were excavating at Buena Vista, an ancient settlement in the foothills of the Andes an hour's drive north of Lima, Peru. A dozen archaeology students hauled rocks out of a sunken temple and lobbed them to each other in a human chain. Suddenly, Bernardino Ojeda, a Peruvian archaeologist, called for the students to stop. He had spotted bits of tan rope poking out of the rubble in the temple's central room. Ojeda handed his protégés small paintbrushes and showed them how to whisk away centuries of dirt. From the sickeningly sweet odor, he suspected that the rope wasn't the only thing buried beneath the rocks: most likely, it was wrapped around a corpse.

"Burials here have a distinctive smell," says Neil Duncan, an anthropologist at the University of Missouri, "even after 4,000 years."

The crew spent the rest of the day uncovering the remains, those of a woman in her late 40s, her body mummified by the dry desert climate. Two intertwined ropes, one of braided llama wool and the other of twisted cotton, bound her straw shroud, bundling the skeleton in the fetal position typical of ancient Peruvian burials. Nearby, the researchers found a metal pendant that they believe she wore.

The mummy—the only complete set of human remains yet recovered from Buena Vista—may play a role in a crucial debate about the origin of civilization in Peru. The excavation's leader, Robert Benfer, also of the University of Missouri, is analyzing bones from the site for signs of what people ate or the sort of work they did. He hopes the analyses will shed light on a controversial theory: that these ancient Peruvians established a complex, sedentary society relying not just on agriculture—long viewed as the catalyst for the first permanent settlements worldwide—but also on fishing. If so, Benfer says, "Peru is the only exception to how civilizations developed 4,000 to 5,000 years ago."

As it happens, one of his liveliest foils in this debate is Neil Duncan, his collaborator and Missouri colleague. Both agree that some farming and some fishing took place here. But the two disagree about how important each was to the ancient Peruvians' diet and way of life. Duncan says these people must have grown many plants for food, given evidence that they also grew cotton (for fishing nets) and gourds (for floats). Benfer counters that a few useful plants do not an agriculturalist make: "Only when plants become a prominent part of your diet do you become a farmer."

Benfer and his team began excavating at Buena Vista in 2002. Two years later they uncovered the site's most notable feature, a ceremonial temple complex about 55 feet long. At the heart of the temple was an offering chamber about six feet deep and six feet wide. It was brimming with layers of partially burned grass; pieces of squash, guava and another native fruit called lucuma; guinea pig; a few mussel shells; and scraps of cotton fabric—all capped by river rocks. Carbon-dated burned twigs from the pit suggest the temple was completed more than 4,200 years ago. It was used until about 3,500 years ago, when these occupants apparently abandoned the settlement.

A few weeks before the end of the excavation season, the archaeologists cleared away rocks from an entrance to the temple and found themselves staring at a mural. It was staring back. A catlike eye was the first thing they saw, and when they exposed the rest of the mural they found that the eye belonged to a fox nestled inside the womb of a llama.

Within days, Duncan spied a prominent rock on a ridge to the east. It lined up with the center of the offering chamber, midway between its front and back openings. The rock appeared to have been shaped into the profile of a face and placed on the ridge. It occurred to Benfer that the temple may have been built to track the movements of the sun and stars.

He and his colleagues consulted astronomer Larry Adkins of Cerritos College in Norwalk, California. Adkins calculated that 4,200 years ago, on the summer solstice, the sun would have risen over the rock when viewed from the temple. And in the hours before dawn on the summer solstice, a starry fox constellation would have risen between two other large rocks that were placed on the same ridge.

Because the fox has been a potent symbol among many indigenous South Americans, representing water and cultivation, Benfer speculates that the temple's fox mural and apparent orientation to the fox constellation are clues to the structure's significance. He proposes that the "Temple of the Fox" functioned as a calendar, and that the people of Buena Vista used the temple to honor the deities and ask for good harvests—or good fishing—on the summer solstice, the beginning of the flooding season of the nearby Chillón River.

The idea of a stone calendar is further supported, the researchers say, by their 2005 discovery near the main temple of a mud plaster sculpture, three feet in diameter, of a frowning face. It resembles the sun, or maybe the moon, and is flanked by two animals, perhaps foxes. The face looks westward, oriented to the location of sunset on the winter solstice.

Other archaeologists are still evaluating the research, which has not yet been published in a scientific journal. But if Benfer is right, the Temple of the Fox is the oldest known structure in the New World used as a calendar.

For his part, Duncan says he maintains "a bit of scientific skepticism" about the temple's function as a calendar, even though, he says, that view supports his side in the debate about early Peruvian civilization. Calendars, after all, "coincide with agricultural societies." And referring to the vegetable-stuffed offering pit, he asks, "Why else would you build such a ceremonial temple and make offerings that were mostly plants?"

But Benfer hasn't given up on the theory that ancient Peruvians sustained themselves in large part from the sea. How else to explain all the fish bones and shells found at the site? And, he says, crops would fail if the fickle Chillón River did not overflow its banks and saturate the desert nearby, or if it flooded too much. "It's difficult to make it just on plants," he says.

So even after several seasons' worth of discoveries, Benfer and Duncan are still debating—collegially. As Benfer puts it, "I like it that his biases are different than mine."

Anne Bolen, a former staff member, is now managing editor of Geotimes.