The Orchid Olympics

Breeders from 19 countries put their creations to the test at the 20th World Orchid Conference in Singapore

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Orchid-Olympics-631.jpg)

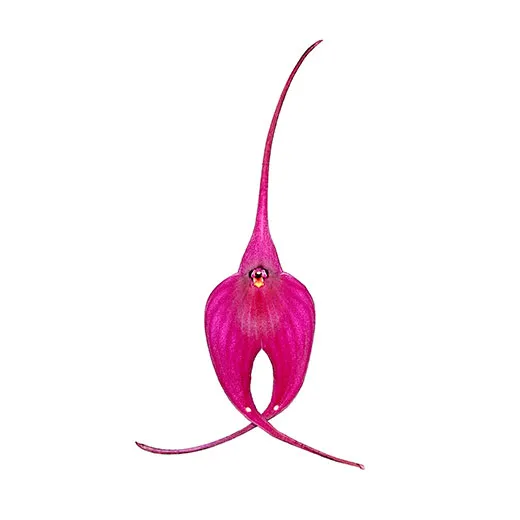

Orchids are seducers. They trick animals into pollinating them and usually give nothing in exchange. Some orchid species mimic nectar-producing flowers to lure bees; others emit the fetid smell of rotting meat to attract carrion flies. In China, Dendrobium sinense orchids release a chemical normally broadcast by bees in distress; the scent attracts bee-eating hornets expecting an easy meal. The scent of Cymbidium serratum entices a wild mountain mouse, which spreads pollen from flower to flower with its snout. And around the world, orchid species have evolved to look or smell like female insects; males try to mate with the flowers but gather and deposit pollen, which they carry on their flight from deception to deception.

But perhaps the most spectacular evidence of the plant’s powers of attraction could be seen several weeks ago in Singapore, at the 20th World Orchid Conference, a triennial affair that drew about 1,000 participants from 55 countries and more than 300,000 spectators. It was one of the largest orchid competitions in history, a colorful, heavily scented affair that showcased the growing popularity and cutting-edge science of orchid breeding.

“Orchids are such manipulators. After the birds and the bees, they have enticed us humans into doing the dirty deed for them,” joked Kiat Tan, chairman of the conference’s organizing committee.

The day before the conference, the four-acre exhibition hall in Singapore’s convention center was strewn with half-opened crates: “Fragile! Handle with care. Store at 8 degrees C.” Hundreds of jet-lagged exhibitors delicately extracted cut flowers and orchid plants from their packaging. Some had carried their orchids by hand on flights and through customs, with the requisite certifications that the plants were disease-free and approved for travel by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species.

The flowers “tend to suffer if it’s too cold or sweat if it’s too warm in the boxes,” said Chris Purver, an orchid breeder and curator with the Eric Young Orchid Foundation on the Isle of Jersey, a British crown dependency. “We had a few sleepless nights in getting them here.”

Members of a South African orchid society, disappointed that international trade regulations had denied them permission to bring real animal parts or live birds, huffily constructed a jungle display with fake leopards, rhino horns and elephant tusks.

Justin Tkatchenko, from the Orchid Society of Papua New Guinea, was adding finishing touches to a display that included gigantic carved masks and a bird made of orchids. “We are aiming to be the best in the world. This will be the most photographed display in the whole show,” he said.

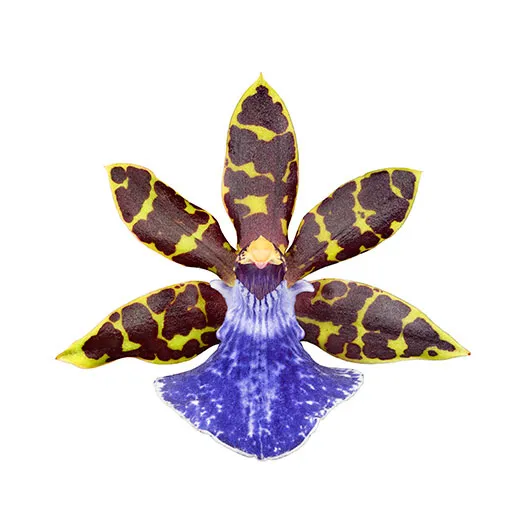

Orchids may be the most diverse flower family in the world, with more than 25,000 species. (Their only competition comes from daisies.) The orchid family maintains such diversity in the wild in part because individual orchid species summon only specific pollinators; the flowers thus avoid mingling their genes with those of other nearby orchids that are visited by their own pollinators. But most of the 50,000 orchids from 5,000 varieties on display at the conference do not occur in the wild; they are hybrids, created by people who have cross-fertilized orchid species, often from far-flung lands.

“The joy of breeding orchids is to see if you can combine two species in order to create something even more beautiful than either of the parents,” Martin Motes, a commercial grower from Florida and conference judge, said as visitors poured into the hall and crowded around the displays. He has been breeding orchids for 40 years, and many varieties of his 500 hybrids are named after his wife, Mary. “My wife thinks I am playing God! Well, man is given dominion over the beasts of the fields and orchids of the greenhouse, I guess,” he said.

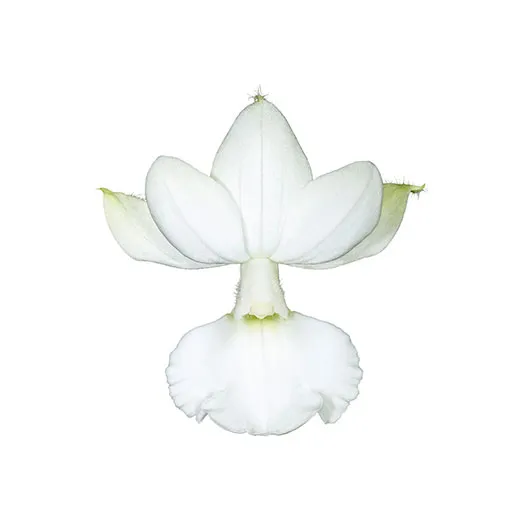

An orchid breeder begins with a vision—the color, shape, size, fragrance and longevity of the desired flower—and then searches for the ideal parents. “When we craft orchids for celebrities and delegates, we also consider their tastes, personalities and occupation, said Tim Yam, a senior researcher and orchid breeder at the Singapore Botanic Gardens. “For example, the orchid named for Princess Diana was white—the color of royalty—and very fragrant. But if it’s for a prime minister or president, we might choose a deeper color and majestic spray.”

At the Orchid Breeding and Micropropagation Laboratory of the Singapore Botanic Gardens, Yam showed me how orchids are grown in the lab. The tiny seeds are strewn on nutrients in a sterile glass flask; after a few months, the seedlings are transferred to new flasks. Generally, they spend their first year under glass, their second year in community pots, their third in individual thumb pots. Only after four years do they begin to flower. The plants with the most favored characteristics, such as vigor, length of spray, and size, shape and color of flowers, are then cloned. A meristem, or growth tip, is clipped from the orchid and shaken in a flask. Normally a meristem produces one shoot, but “shaking the plant tissue confuses it and it will start producing many shoots,” Yam said. Growers separate the shoots to produce clones of the same hybrid.

Gone are the days when owning an orchid was a luxury. Thanks to cloning, orchids can be grown en masse, and you can buy a stem at the grocery store for $20. Orchids are the most commonly sold type of potted flowering plant in the United States, where the wholesale business reached $171 million in 2010, up 6 percent from the year before.

At the conference, a retired English professor, a cattle farmer from South Africa, a patent attorney from Singapore and an Italian fashion designer living in Bali mingled in the crowd. People discussed voluptuous bodies with slick curves, unblemished skin, flamboyant posture and perfectly curved luscious lips.

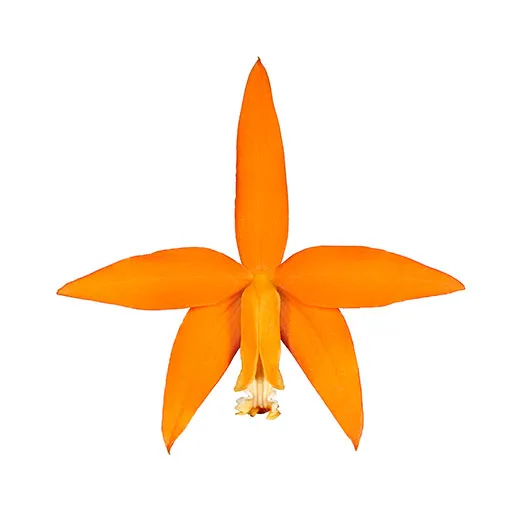

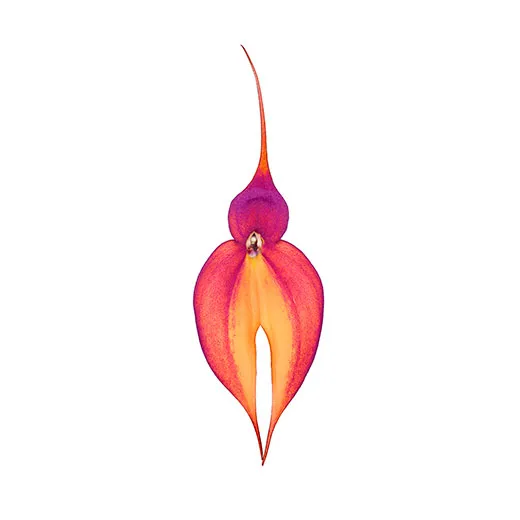

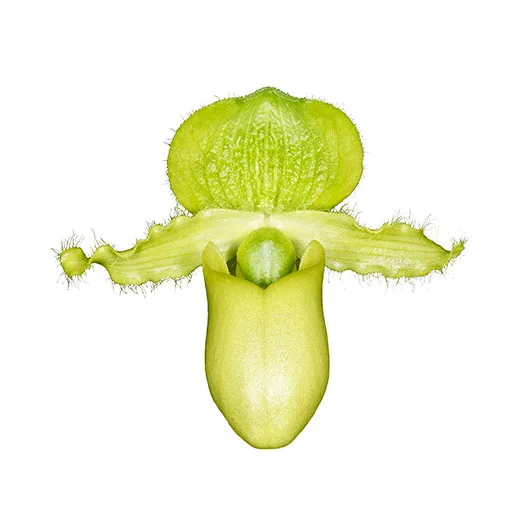

“Orchids are fascinating because they are shaped just like us—two sepals and two petals on either side,” said Motes, gesturing with his sepal-like legs and petal-like arms. “There’s a dorsal sepal at the top, a central column and a lip at the bottom that’s actually a landing pad for potential pollinators,” he went on. “This intricate structure of orchids tends to be sensual and touches something primal in us on a subliminal level.”

Another exhibitor, Haruhiko “Harry” Nagata, and his family hand-carried 275 orchid plants and 26 cut flowers from Japan to Singapore. “I have been growing orchids for 35 years and for me breeding orchids is all about fun and anticipation—pollinating two plants with different characteristics and getting to see the first bloom after several years!” he said. Nagata’s contender for the show’s big prize was a flamboyant white orchid with an exotic purple-tinged lip, named Mikkie Nagata, after his wife. Pointing to a pink flower, he said, “This is Cattleya Jimmy Nagata, named after my son. Very, very lousy,” he joked, pointing to his son in the distance. “But the flower is OK!”

When judging commenced, more than 200 connoisseurs, most with salt-and-pepper hair and clad in loose clothes and comfortable running shoes, scrambled from one exhibit to another armed with judging sheets, measuring tapes and laser pointers. Some examined from a distance, while others sat on their haunches and lifted the leaves delicately with a pen.

“My flowers have really done well, a lot of medals and ribbons,” said Purver, the Isle of Jersey grower. “I will be disappointed if I don’t win the big prize.”

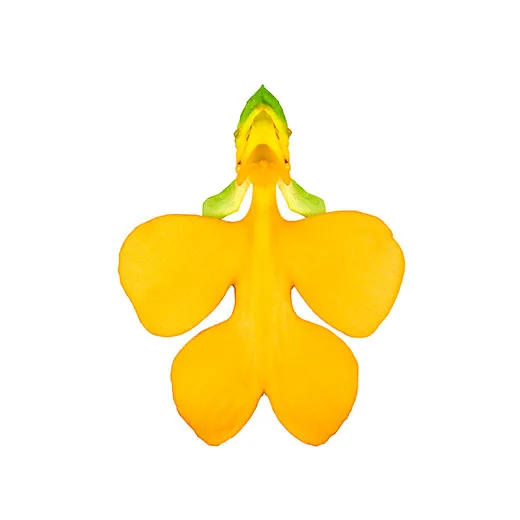

But his entry was a runner-up in the best plant category, losing to a Taiwanese competitor whose winning orchid, Cycnodes Taiwan Gold, had a rich yellow flower that resembled the shape of a swan. The Orchid Society of Papua New Guinea also won a runner-up trophy, for overall display. Wiping tears of joy, Tkatchenko said, “This is absolutely sensational. Who knew where Papua New Guinea was and now we’re up against the world’s best!”

Somali Roy is a writer based in Singapore. JG Bryce, based in Taipei, Taiwan, is working on an art project about perceptions and deceptions.