The Origins of Futurism

The celebrated science fiction writer and author of Tomorrow Now, explains why you don’t need to be clairvoyant to predict the future

Modern futurism began at the dawn of the 20th century with a series of essays by H.G. Wells, which he called “Anticipations.” Wells proposed that serious thinkers should write soberly, factually and objectively about the great “mechanical and scientific progress” transforming human affairs. But if the goal of futurism is to shed enlightenment over the dark forces of historical change, then we must recall that history is one of the humanities, not a hard science. Tomorrow obeys a futurist the way lightning obeys a weatherman.

Still, while it might be impossible to know the future, that hasn’t stopped people from forecasting it—and sometimes in ways that are of real, practical use.

The first way is statistical: to analyze the hard data collected by government and businesses, and sift out underlying trends. It’s demographic research, not clairvoyance, that predicts a new Starbucks coffee shop will appear in a heavily foot-trafficked urban locale.

The second way is reportorial. The future is often a dark mystery to people because they haven’t invested the effort to find out what’s likely to happen. Some simple shoe-leather spadework (interviews, search engines, social networks), coupled with the basic questions of who, what, when, where, how and why, can be of great use here. (This method is the basis for what has become known as “Open Source Intelligence.”)

The third method, historical analogy, is radically inaccurate yet also dangerously seductive, because people are profoundly attached to the seeming stability of the past. In practice, though, our ideas of what has already happened are scarcely more solid than our predictions of tomorrow. If futurism is visionary, history is revisionary.

The fourth method involves a set of strange rituals known as “scenario forecasting,” which assists bewildered clients who can’t frankly admit to themselves what they already know. The job is to encourage mental change through various forms of playacting and rehearsal.

The fifth and final method is the most effective of all. If individuals have never encountered modernity, then you can tell them about real, genuine things that already are happening now—for them, that is the future.

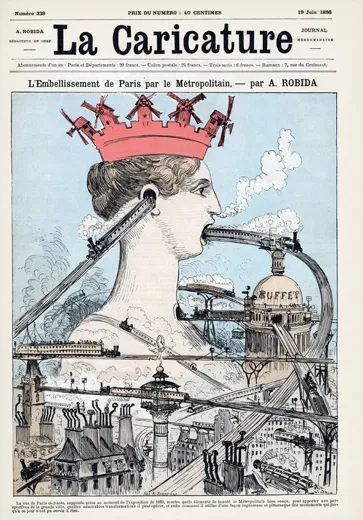

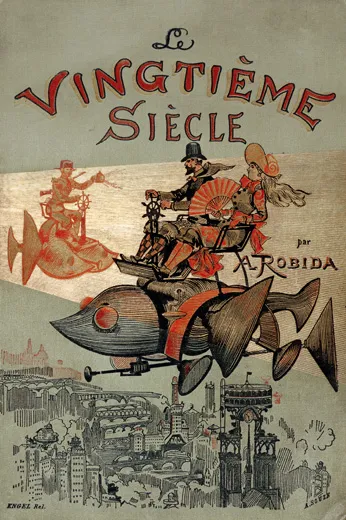

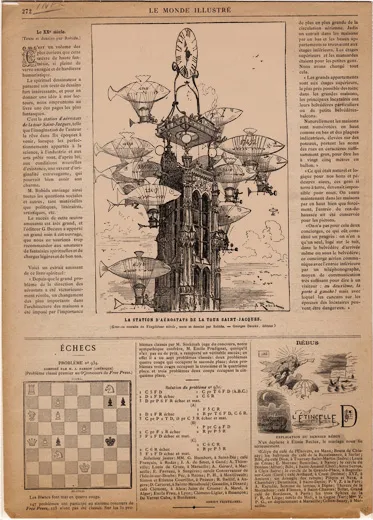

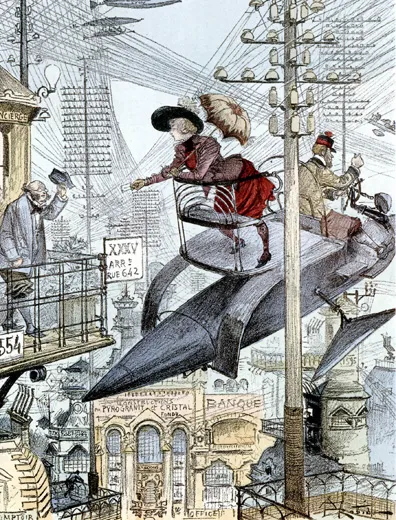

Put another way, the future is already upon us, but is happening in niches. The inhabitants of that niche may be saint-like pioneers with practical plans for applying technology to eliminate hunger or preserve the environment. Far more commonly, they’re weird people with weird ideas and practices, and are objects of ridicule. By that criterion, the greatest futurist of the 19th century was not H.G. Wells, but the French cartoonist Albert Robida.

Robida was a satirist whose intent was to provoke an uneasy, rueful chuckle. He illustrated many pamphlets and novels (some his own) about the 20th century: the future uses of electricity, flying machines, the emancipation of women and other far-out prospects. These subjects seemed hilarious to Robida, but since they predict our past rather than his future, for us, today, they possess an uncanny beauty. Through accepting the embarrassing qualities of the future, Robida’s sly lampoons became brutally accurate. They hit the 20th century like a pie in the face.

The 20th century scarcely noticed Robida’s predictive successes. A forecast is just a phantom; it is dispassionate and unlived, unsupported by the human heartbeat of lived joy and suffering. Even the cleverest, most deeply insightful forecast becomes paper thin when time passes it by. Visions of the future are destined to fade with the dawn of tomorrow.