The Orionid Meteor Shower Will Light Up the Skies This Weekend

Debris shed by the legendary Halley’s comet could make for an impressive meteor show

![]()

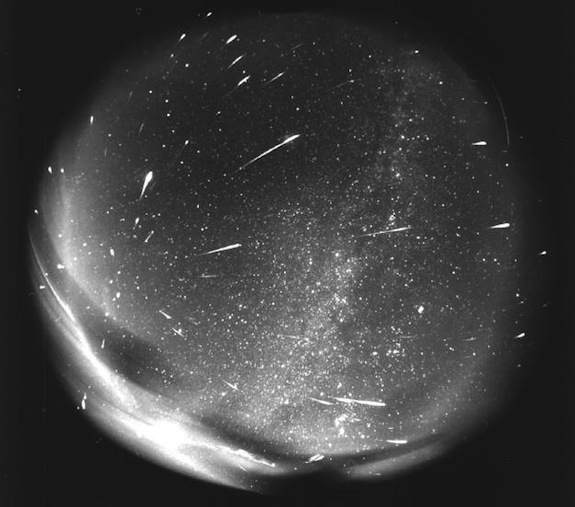

The Orionid shower could produce 20 to 60 meteors per hour early Sunday morning. Image via Wikimedia Commons/Juraj Tóth

Halley’s Comet last visited us in 1986, and it isn’t scheduled to pass by earth again until 2061. This weekend, though, you might get to see debris from the legendary comet light up the night sky. The Orionid meteor shower will peak early Sunday morning across the United States, as the earth crosses through a cloud of debris thrown off the comet during its 75-year-long orbit around the sun.

“Earth is passing through a stream of debris from Halley’s Comet, the source of the Orionids,” said Bill Cooke, head of NASA’s Meteoroid Environment Office. “Flakes of comet dust hitting the atmosphere should give us dozens of meteors per hour.”

Comets heat up as they travel towards the sun, leaving behind tails of dust, ice, rock and other particles. Some of this debris lingers, and each fall—usually around mid-October—the earth passes through a cloud of Halley’s Comet debris. When the particles enter the atmosphere at extremely high speeds, they disintegrate in a burning flash, producing a momentary streak of light across the sky known as a meteor:

Meteors are produced when remnants of debris left by comets incinerate as they descend through earth’s atmosphere. Image via NASA

The Orionid meteor shower is named because, from our vantage point, it appears that all of its meteors emanate from a single point, a bit to the left of the constellation Orion. For all meteor showers, in fact, the meteors seem to come from a fixed point (called the radiant) that slowly moves across the sky during the night. This is because of perspective, the same way that a long straight road appears to terminate at a single point on the horizon.

This year, the Orionids should be especially impressive because our passing through the densest part of the debris cloud coincides with a quarter moon, providing relatively less light to drown out meteors in the sky. Additionally, the moon will have set entirely by 3 a.m. Typically, the shower produces about 20 meteors an hour—or one every few minutes—but in recent years, meteors in the Orionid shower have been observed to grow more frequent. ”Since 2006, the Orionids have been one of the best showers of the year, with counts in some years up to 60 or more meteors per hour,” Cooke said.

Especially brilliant meteors can produce multi-colored flashes of light, like this one from the 2007 Orionid shower. Image via Wikimedia Commons/Brocken Inaglory

NASA recommends heading outside a few hours before dawn on Sunday morning for your best shot at seeing some meteors. Look to Orion, which will start in the eastern portion of the sky around midnight and gradually move southward, to find the radiant from which the meteors will emanate. Darkness is crucial, so turn off outdoor lights or travel to the darkest location possible.

Some skywatchers around the country are reporting already seeing meteors in the days leading up to the shower’s peak. In Northern California, hundreds of residents reported hearing an booming sound and seeing explosive streaks of light around 7:45 p.m. Wednesday evening. This was likely caused by a particularly large piece of debris entering the atmosphere, explained Jonathan Braidman, an astronomer at the Chabot Space & Science Center in Oakland, to ABC News: “Basically, you saw small car-sized pieces of rock and metal from the ashtray belt, crashing through layers of earth’s atmosphere, ionizing and setting the air on fire in its wake.”

If you live in a light-filled city, or if cloudy weather ruins your chance to see the show, NASA is providing a streaming video feed of the shower via camera mounted at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. From 11 p.m. on Saturday night to 3 a.m. Sunday morning, they’ll also have astronomer Mitzi Adams on hand to answer meteor-related questions in a live chat.

Over the coming months, several other notable meteor showers are due up as well. The most prolific of these, the Leonids, should peak around November 17.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)