The Rise and Fall and Rise of the Chemistry Set

Banning toys with dangerous acids was a good idea, but was the price a couple generations of scientists?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ChemistrySet-hero-631.jpg)

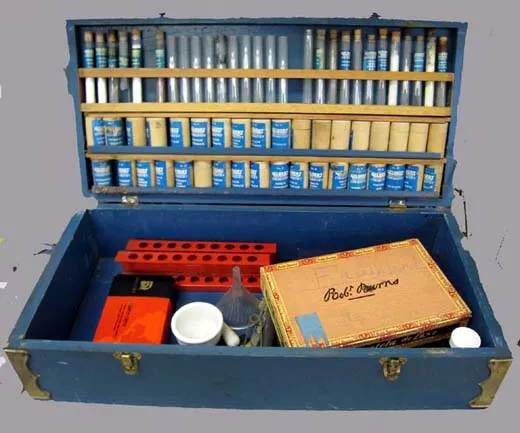

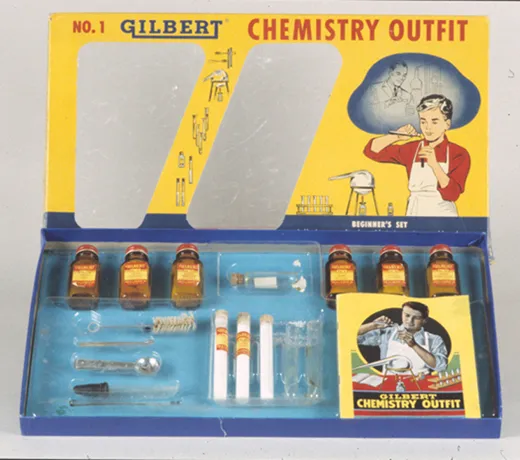

The chemistry set had clearly seen better days. Curator Ann Seeger pulls the mid-20th-century Gilbert kit out of a glass-fronted cabinet in the back of a cluttered storeroom at the National Museum of American History and opens the bright blue wooden box, revealing that several bottles of chemicals are missing and some vials have lost their labels. The previous owners hadn’t let a few missing pieces stop them, though; the kit was supplemented with a set of plastic measuring spoons that appear to have been stolen from a mother’s kitchen.

One of the museum’s librarians donated the kit; he and his brother had played with it as children. “They weren’t very good with chemistry,” Seeger says, which may explain the donor’s career choice.

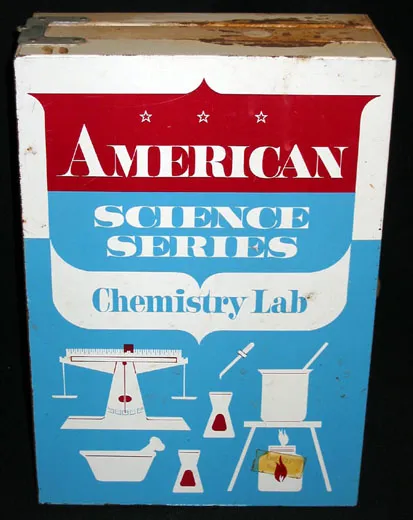

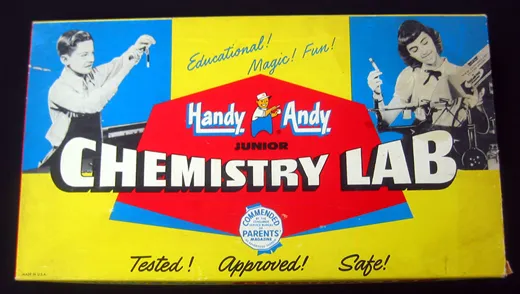

The museum’s collection contains several brightly colored kits harkening from the toy’s brief heyday in the early- to mid-20th century, when the chemistry set was the must-have toy for the budding scientist. The story of how the chemistry set rose to such prominence and then fell follows the arc of 20th-century America, from its rise as a hub of new commerce to an era of scientific discovery, and reflects the changing values and fears of the American people.

Seeger shows me a small, brown wooden box, circa 1845, about ten-inches square, inset with a small relief of silvery metal, depicting what appears to be a scene from a ship, with men in pantaloons holding swords. A green label on the inside of the lid gives the original purpose of this now-empty box: “G. Leoni’s Portable Laboratory.”

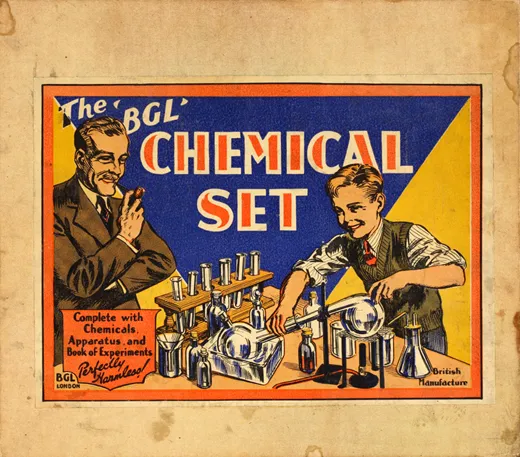

The toy chemistry set has its roots in late 18th- and 19th-century portable chemistry kits sold in boxes like this to scientists and students for practical use. The kits contained glassware, chemicals, perhaps a scale or a mortar and pestle, and other necessary equipment for carrying out chemical tests in medicine, geology or other scientific fields or for classroom instruction.

Many kits were assembled in England, but the chemicals came from Germany. The approach of World War I quickly dried up that supply, as manufacturers diverted remaining resources to the war effort; chemistry set production declined.

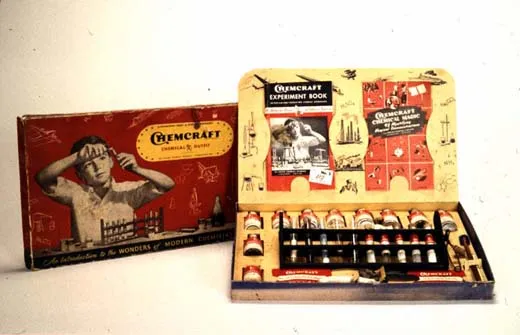

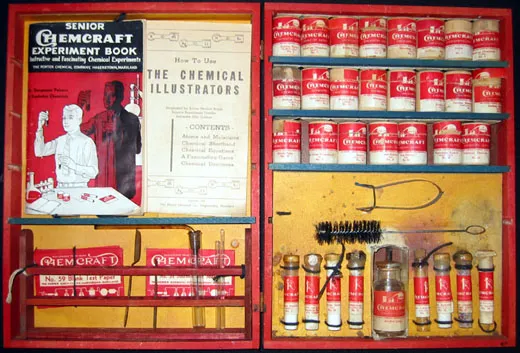

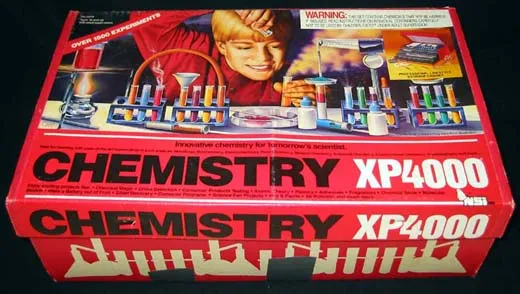

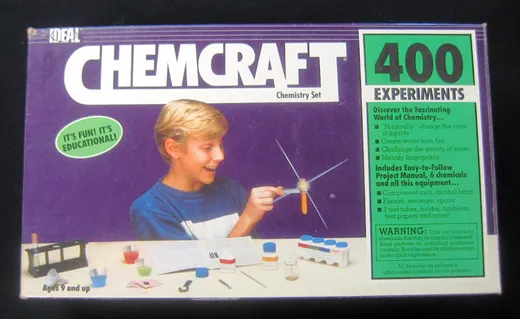

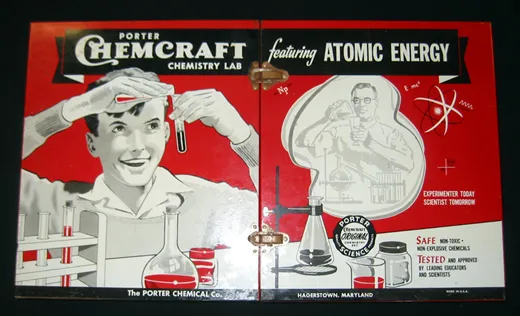

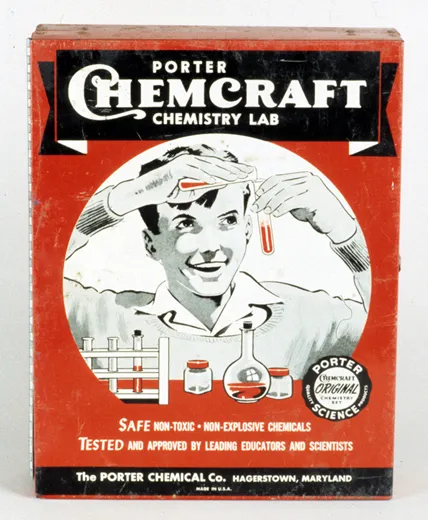

Simultaneously, across the Atlantic in the United States, two brothers, John J. and Harold Mitchell Porter, started up a chemical company in Hagerstown, Maryland, and—inspired by the English chemistry kits and a new toy, the Erector Set, that was gaining popularity—were soon producing toy versions of the chemistry set with the intention of inspiring young boys in science. These Chemcraft kits, as they were called—filled with chemicals, labware, a balance, an alcohol lamp and helpful instructions—soon spread beyond the Washington, D.C. area and were sold in Woolworth’s and other stores around the country. Prices ranged from $1.50 to $10, depending on the complexity of the kit.

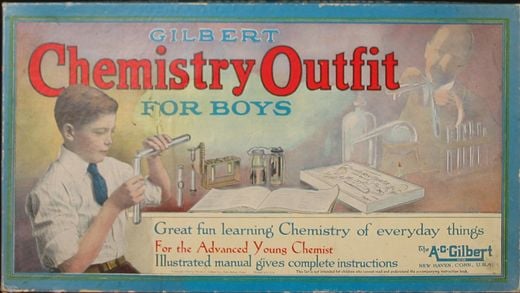

By 1920, Alfred Carlton Gilbert, the inventor who struck big with the Erector Set in 1913, caught on to the trend and expanded his toy business to include selling science. With two major makers competing for customers, the chemistry set was poised for takeoff. The Porter Chemical Company and A. C. Gilbert spent decades vying for customers with ads in kids’ and science magazines, marketing their kits as a path to a future career in chemistry.

“Coming out of the Depression, that was a message that would resonate with a lot of parents who wanted their children to not only have a job that would make them money but to have a career that was stable. And if they could make the world a better place along the way, then even better,” says Rosie Cook, registrar and assistant curator at the Chemical Heritage Foundation in Philadelphia. (CHF houses one of the nation’s best collections of chemistry sets, many of which will go on display in a 2014 exhibition.)

World War II brought a rush of scientific research and booming times for American companies such as Goodyear and DuPont. Following the success of the Manhattan Project, science became part of America’s identity as a world superpower in the years after the war, and government funding poured into research. The space race began and discoveries piled up—the invention of the transistor, the discovery of the structure of DNA, the creation of the polio vaccine—and the marketing of the chemistry set shifted, reflected in the advertising slogan for Chemcraft, “Porter Science Prepares Young America for World Leadership.”

Such slogans weren’t simply clever marketing; the chemistry set was indeed inspiring a generation of great scientists. “When I was 9 years old, my parents gave me a chemistry set. Within a week, I had decided to become a chemist and never wavered from that choice,” recalled Robert F. Curl, Jr. in his Nobel Prize autobiography. Curl Jr. was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1996 for the discovery of buckyballs and was one of many Nobel Prize winners who credit the kits for inspiring their career.

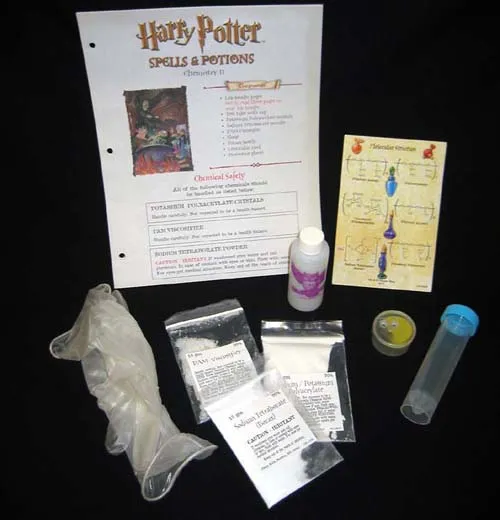

Most of the chemicals and equipment in these chemistry kits were harmless, but some would make even the most lenient modern parent worry: Sodium cyanide can dissolve gold in water, but it is also a deadly poison. “Atomic” chemistry sets of the 1950s included radioactive uranium ore. Glassblowing kits, which taught a skill still important in today’s chemistry labs, came with a blowtorch.

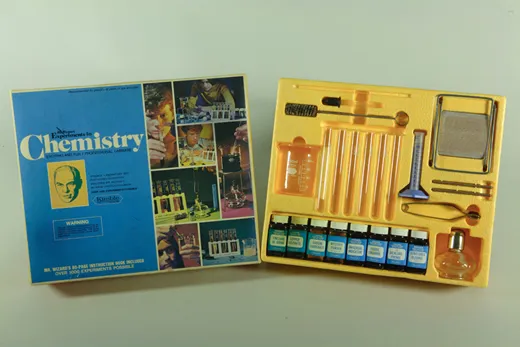

The safety-conscious 1960s brought a quick end to the chemistry set’s popularity. The Federal Hazardous Substances Labeling Act of 1960 required labels for toxic and dangerous substances, and chemistry set makers removed the alcohol lamps and acids from their kits. The Toy Safety Act of 1969 removed lead paint from toys but also took its toll on the sets. The creation of the Consumer Product Safety Commission in 1972 and the passing of the Toxic Substances Control Act in 1976 resulted in further limits on the contents of the kits. Newspapers that once broadcast the arrival of new kinds of chemistry sets soon warned of their dangers, recommending that they only be given to older children and kept locked up from their younger siblings. “The death of the chemistry set is almost an unintended consequence of the rise in consumer protection laws,” says Cook.

This era also saw a boost in environmental awareness and a distrust of chemistry and government-funded science. Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, warning of the deleterious effects of pesticides. The anti-nuclear movement was on the rise. The American people were becoming aware of the devastating effects of Agent Orange, the chemical defoliant used in Vietnam. And by the 1970s and 1980s, science had lost its magic, as had the chemistry set.

The last chemistry set that Seeger shows me dates to 1992—it’s a Smithsonian-branded kit developed under the guidance of her predecessor, John Eklund. “It’s completely different from the older sets,” Seeger notes, pointing out the safety goggles, the replacement of anything glass with plastic and warning labels that are larger than the names of the chemicals. The box boasts that it is “the safest chemistry set made.”

The 1980s brought a new set of societal problems—AIDS, Chernobyl, the ozone hole—but people now looked again to science for solutions. The chemistry set reemerged, though dramatically changed. There were fewer chemicals, or no chemicals, and safety was a priority.

Michelle Francl, a theoretical chemist at Bryn Mawr College, wonders whether that emphasis on safety may actually be making young scientists less safe. “I get students who I can’t get to wear eye protection in the lab or closed-toe shoes,” she says. “We let kids play soccer, play football, ride bikes, all of which are inherently more dangerous than most of the things they could do with a chemistry set.”

The worst that happened during Francl’s own young adventures in home chemistry was when her brother lost an eyebrow, and that wasn’t even related to a chemistry set experiment. “We had one very memorable explosion, which we managed to keep from my mother,” Francl recalls. The pair had scrounged the equipment to separate hydrogen and oxygen from water. Their instructions recommended testing for the presence of hydrogen with a glowing ember—luckily, they were working in a makeshift basement lab where there was nothing flammable. “It didn’t make a big mess. There was just a big poof,” she says.

In an era of helicopter parenting, risk aversion and litigation—not to mention the rise of meth labs across the country—it might seem that even the neutered chemistry set is doomed to another death.

But the 21st century has also seen a new host of problems for science to solve, including how to provide food, water and power to a global population that will pass ten billion by 2100. Government and business leaders are putting renewed emphasis on science education. And the chemistry set has seen a bit of a resurgence. Educational toy retailer Discover This reported strong sales of chemistry sets during last year’s Christmas season, anchored by a revamped line of traditional chemistry sets from Thames & Kosmos. Cook says that the sets are very similar to the Chemcraft and Gilbert sets of the early 20th century but may be even better for learning science. They are sold in four steps of kits of increasing difficulty that encourage learning the basics before moving on to harder tasks. Cook raved about the manuals: “Not only do they tell you what you’re learning and break it into types of experiments, [but also] they tell you the history behind the discovery,” as well as how to dispose of experiments, “which is really helpful today, because you can’t just dump things down the drain.”

But the reality is that a traditional chemistry set is probably no longer necessary for performing chemistry at home. Books and manuals are readily available and equipment and chemicals can be bought online or scrounged from around the house, like Francl did when she was young. And while safety should be a concern, parents should recognize that most home chemistry accidents happen not from kids mixing chemicals in the basement but from adults mixing cleaning supplies upstairs. “The things that kill people, if you look at the accidents in homes, are people mixing bleach with everything from ammonia to pesticides,” Francl says.

Home experimentation has inspired scientists and inventors for years, and it would be a shame if concerns about safety stopped budding chemists from getting a start. “I would encourage parents to let their kids be a little risky and let them try things where it might be complicated to work,” Francl says. And, “Be patient with the mess.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)