The Rock of Gibraltar: Neanderthals’ Last Refuge

Gibraltar hosted some of the last-surviving Neanderthals and was home to one of the first Neanderthal fossil discoveries

![]()

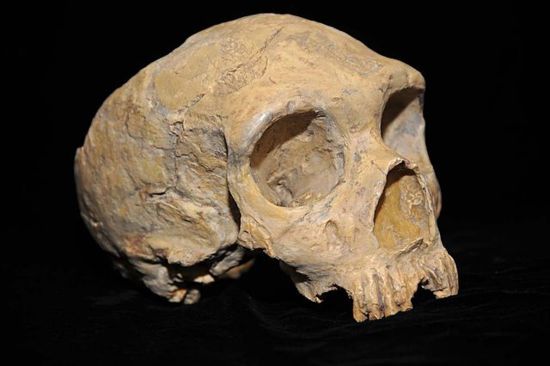

In 1848, an officer in the British Royal Navy found the first Gibraltar Neanderthal fossil, the skull of an adult female. Image: AquilaGib/Wikicommons

I was intrigued when I saw this headline over at NPR’s 13.7 blog earlier this week: “A Neanderthal-Themed Park for Gibraltar?“ As it turns out, no one’s planning a human evolution Disney World along Gibraltar’s cliffs. Instead, government officials are hoping one of the area’s caves will become a Unesco World Heritage site. Gibraltar certainly deserves that distinction. The southwestern tip of Europe’s Iberian Peninsula, Gibraltar was home to the last-surviving Neanderthals. And then tens of thousands of years later, it became the site of one of the first Neanderthal fossil discoveries.

That discovery occurred at Forbes’ Quarry in 1848. During mining operations, an officer in the British Royal Navy, Captain Edmund Flint, uncovered an adult female skull (called Gibraltar 1). At the time, Neanderthals were not yet known to science, and the skull was given to the Gibraltar Scientific Society. Although Neanderthals were recognized by the 1860s, it wasn’t until the the first decade of the 20th century that anatomists realized Gibraltar 1 was indeed a Neanderthal. Additional Neanderthal discoveries came in the 1910s and 1920s at the Devil’s Tower rock shelter, which appeared to be a Neanderthal occupation site. In 1926, archaeologist Dorothy Garrod unearthed the skull of a Neanderthal child near flaked stone tools from the Mousterian industry. In all, archaeologists have found eight Neanderthal sites at Gibraltar.

Today, excavations continue at Gorham’s Cave and Vanguard Cave, where scientists have learned about the life and times of the most recent populations of Neanderthals. In 2006, researchers radiocarbon dated charcoal to estimate that the youngest Neanderthal populations lived at Gibraltar as recently as 24,000 to 28,000 years before the present. Clive Finlayson, director of the Gibraltar Museum’s Heritage Division, has suggested that Neanderthals persisted so late at Gibraltar because the region stayed a warm Mediterranean refuge while glacial conditions set in across more northern Europe. Ancient pollen data and animal remains recovered from Gibraltar indicate Neanderthals had access to a variety of habitats—woodlands, savannah, salt marshes and scrub land—that provided a wealth of food options. In addition to hunting deer, rabbits and birds, these Neanderthals enjoyed eating monk seals, fish, mussels and even dolphins on a seasonal basis.

As with most things in paleoanthropology, the Neanderthal history at Gibraltar is not settled. Some anthropologists have questioned the validity of the very young radiocarbon dates. Why the Neanderthals eventually died out is also a matter of debate. Further climate change in Europe, competition with modern humans or some mix of both are all possible explanations.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/science-erin-wyman-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/science-erin-wyman-240.jpg)