The Science Behind Earth’s Many Colors

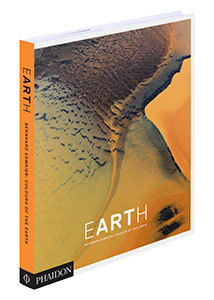

A new book of breathtaking aerial photography by Bernhard Edmaier explains how the planet’s vividly colored landscapes and seascapes came to be

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/19/2f/192f8604-654b-4a82-b325-9963f9aa2d70/2020_innovators_resize.jpg)

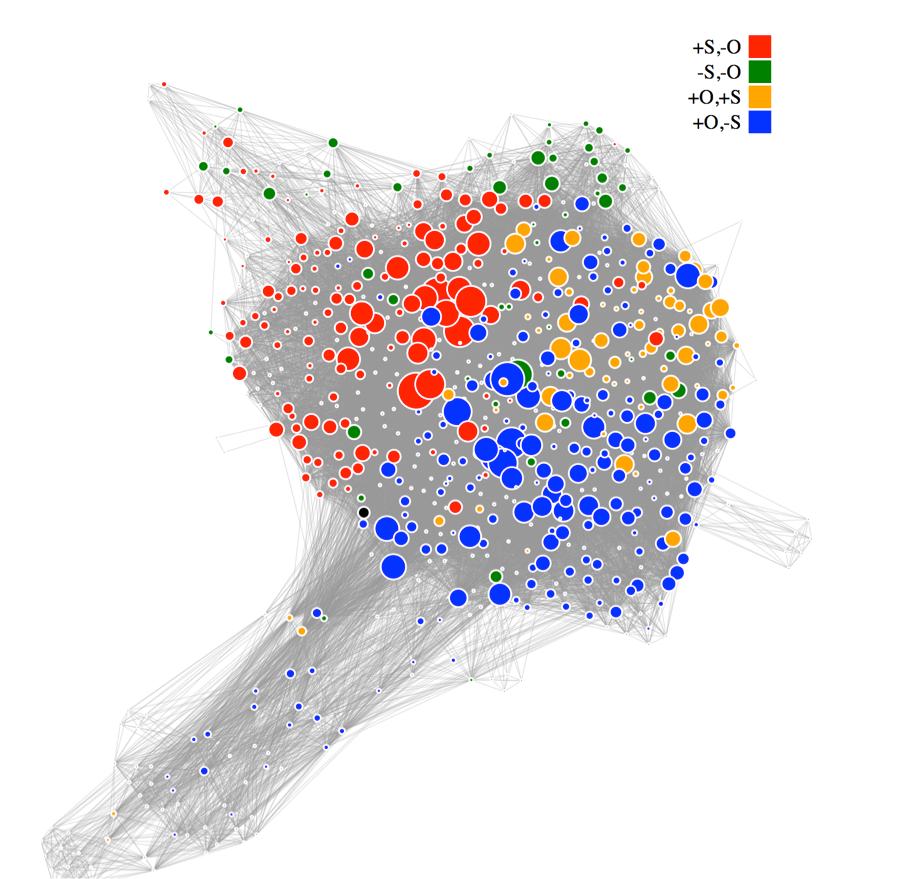

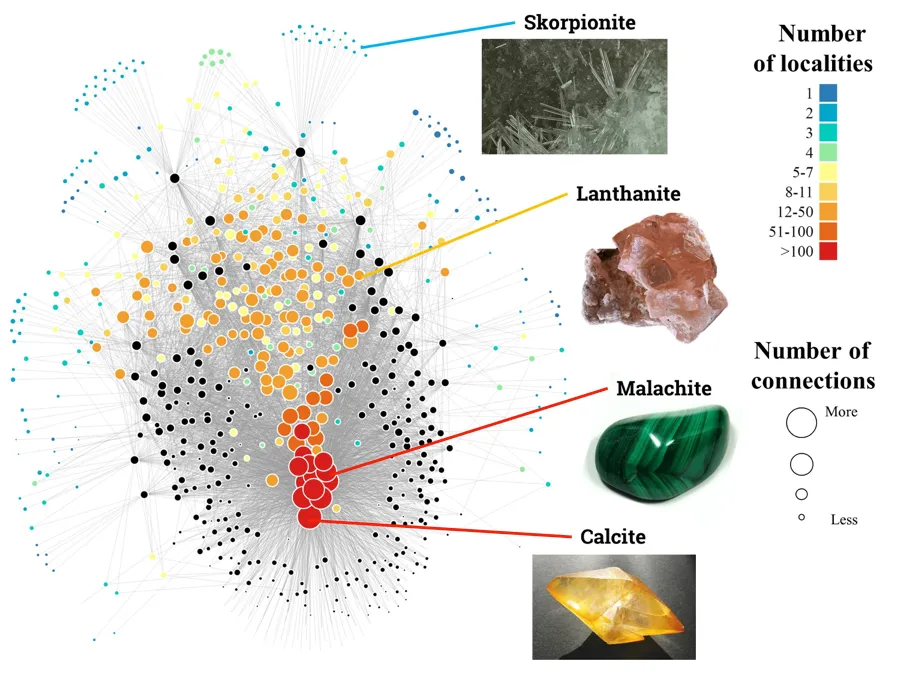

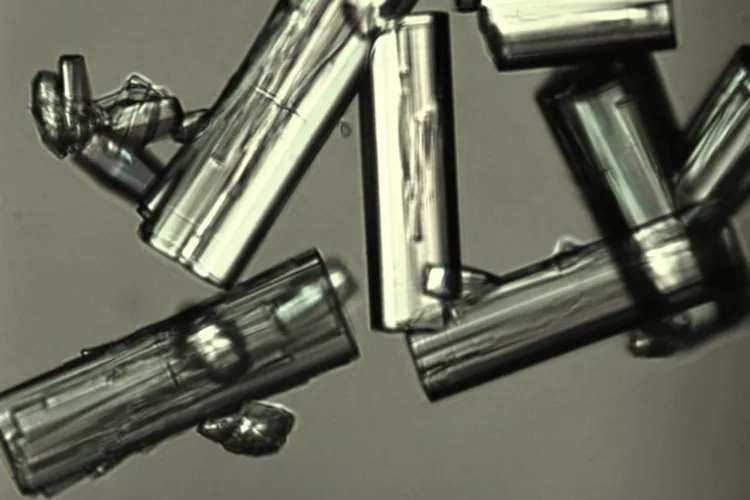

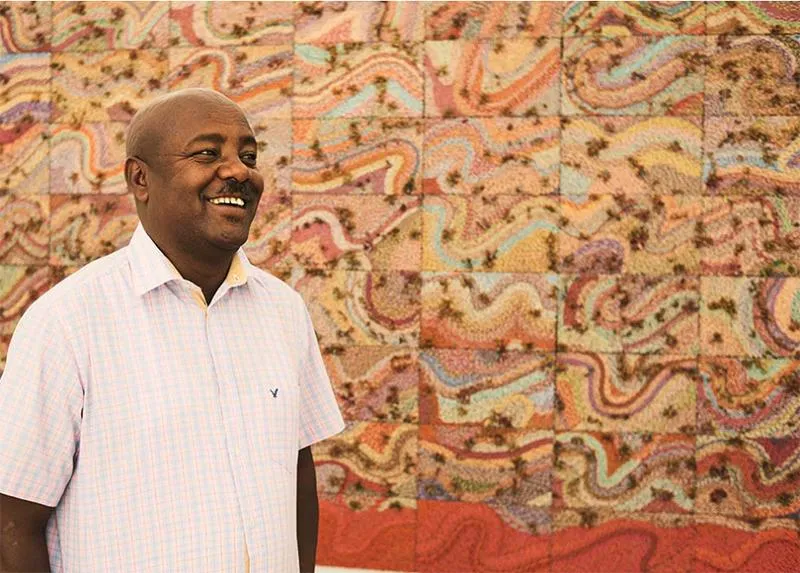

Photographer Bernhard Edmaier is a geologist by training, and it is this knowledge base of the processes that create geological features that he leans on when selecting locations to shoot. For almost 20 years, he has hunted the world over for the most breathtaking views of coral reefs, active volcanoes, hot springs, desert dunes, dense forests and behemoth glaciers.

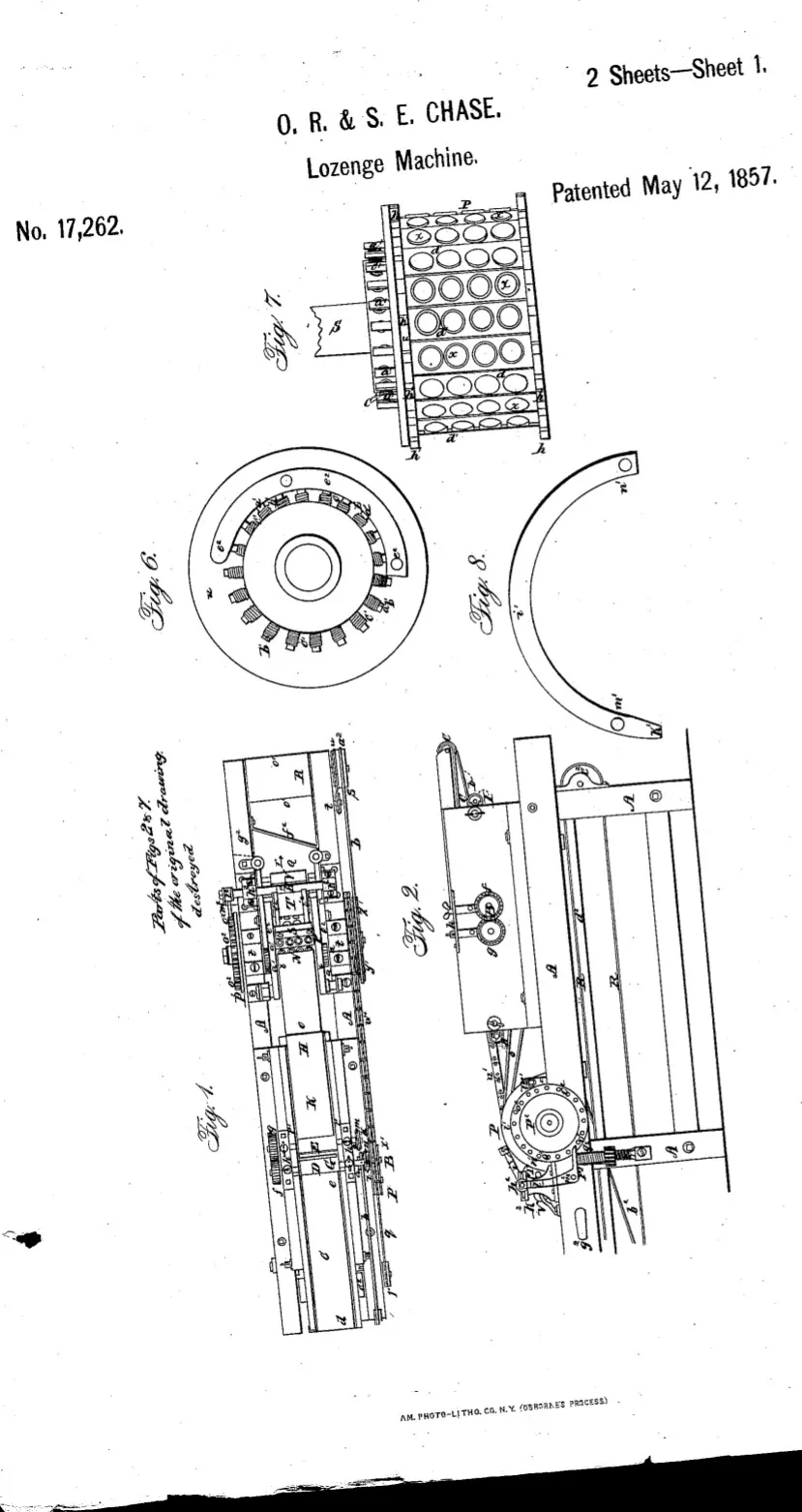

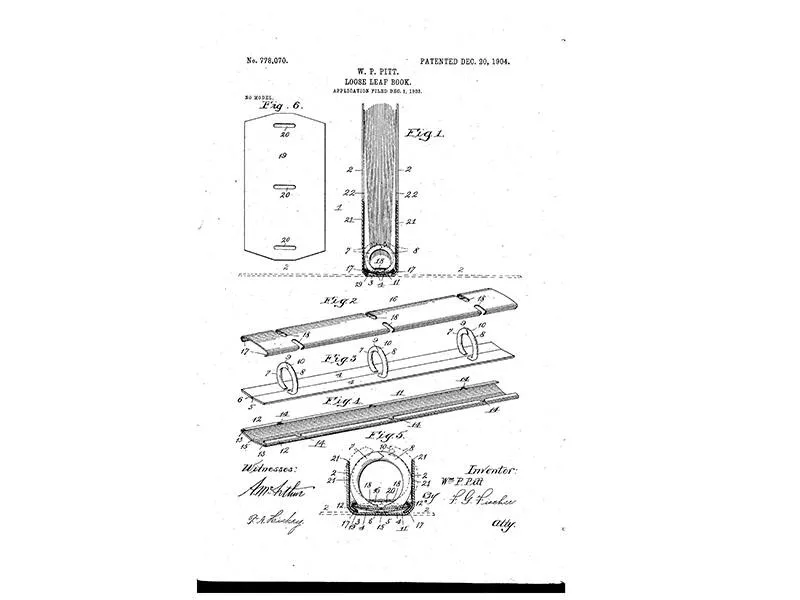

Edmaier’s new book, EarthART (Phaidon), features 150 images organized by color.

“Together with my partner Angelika Jung-Hüttl, I do a lot of internet research, including Google Earth, study satellite images of planned destinations, maintain close contact with local scientists and commercial pilots, deal with various authorities and negotiate flight permits,” says Edmaier. “It can take months of research until the moment of shooting has arrived.”

Then, on that long-awaited day, the German photographer boards a small plane or helicopter and instructs the pilot to position him in just the right spot over the landform. He often has that perfect shot in mind, thanks to his planning, and he captures it out of the side of the side of the aircraft with his 60-megapixel digital Hasselblad camera.

From a logistical standpoint, Edmaier explains, “As my favorite motifs, geological structures, are mostly very large, I need to shoot my images from a greater distance. Only from a bird’s eye view can I manage to capture these phenomena and to visualize them in a certain ‘ideal’ composition.” Then, there are, of course, aesthetics driving his methods. “This perspective perfectly allows me an exciting interplay of concrete documentation and somehow detached reduction and abstraction, with more accentuation of the latter,” he adds.

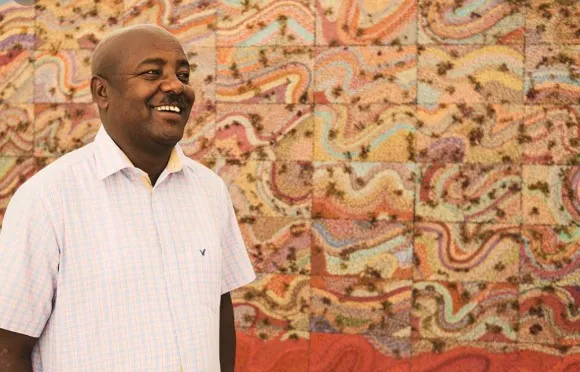

Innauen, German-Austrian border. © Bernhard Edmaier

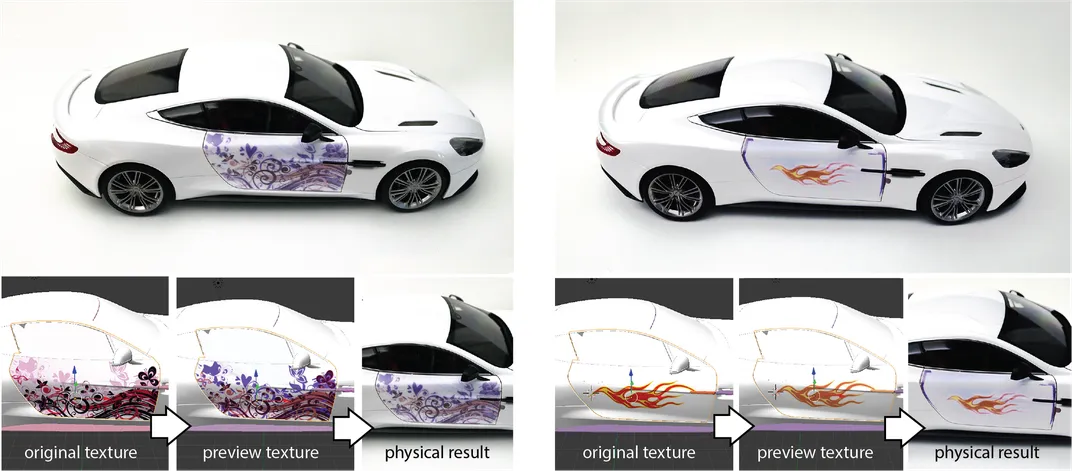

Looking at an Edmaier photograph, your eye might trace a fracture, fault, rock fold or pattern of erosion like it would the stroke of a brush until, without any geographic coordinates or other means of orientation, you find yourself thinking you could be gazing at an abstract painting.

Landeyarsander, Iceland. © Bernhard Edmaier

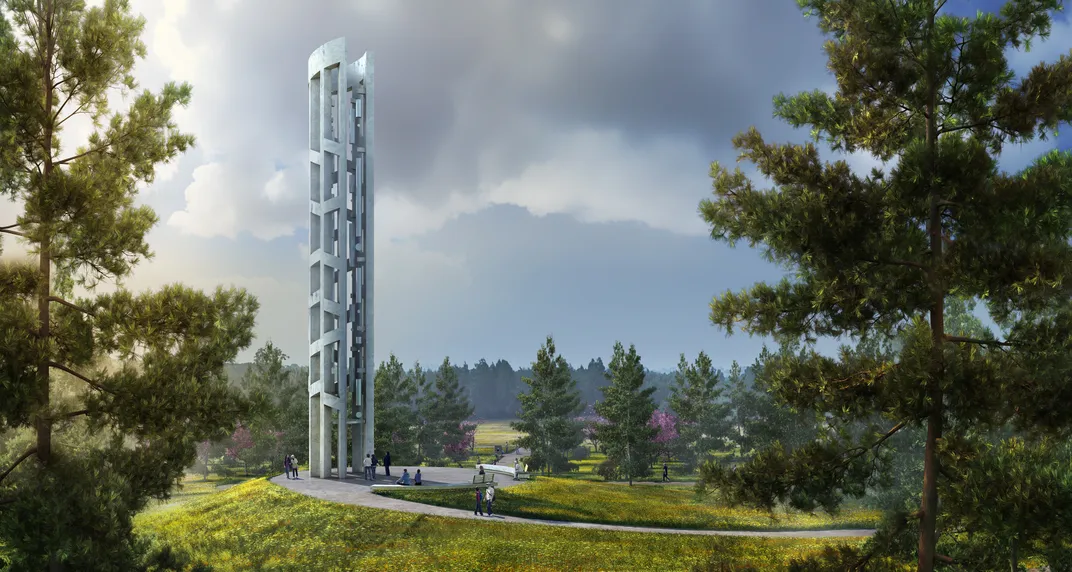

In his new book, EarthART, published by Phaidon, the aerial genius presents a broad survey, from the islands of the Bahamas to the alpine meadows of Italy’s Dolomites and Germany’s Alps, the rugged desert of California’s Death Valley to a bubbling mud pool in New Zealand ominously named “Hell’s Gate,” in 150 images organized–quite beautifully–by color: blue, green, yellow, orange, red, violet, brown, grey and white.

“Each photograph is accompanied by a caption explaining how, where and why these spectacular colors occur: from tropical turquoise seas to icy blue glaciers; from lush green forests to rivers turned green by microscopically small algae,” reads the book jacket. Edmaier was particularly enamored with the Cerros de Visviri, a mountain range on the Chile-Bolivia border that he calls “an orgy of all shades of orange.” The oranges, yellows, reds and browns are the result of a chemical alteration of the iron in volcanic rocks turning to iron oxide and iron hydroxide.

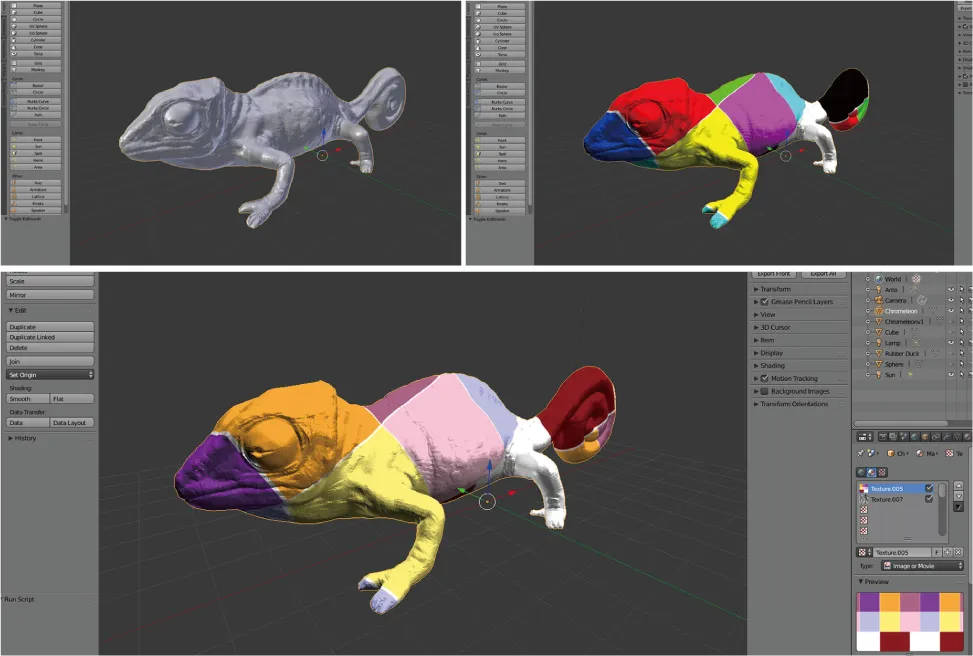

Islands near Eleuthera, Bahamas. © Bernhard Edmaier

The book reads like a plea not to take these colors and geologic wonders for granted. In the introduction, Jung-Hüttl, a science writer, describes how the Earth’s hues developed over 4.6 billion years:

“Our planet was first a grey cloud of cosmic dust, then, following collisions with meteorites and comets, a glowing red fire ball of molten rock, the surface of which cooled off gradually before solidifying to form a dark crust. Enormous quantities of water vapor in the early atmosphere, which was acid and without oxygen, led to intense precipitations on the young earth, which in turn led to the creation of oceans over the course of several millions of years. In the cold regions, the white of the ice fields was added to the blue of the water…The widespread shades of red, yellow and brown first occurred when the earth was half as old as it is today, that is to say around 2 billion years ago. These shades are the result of chemical rock weathering, which only became possible once small amounts of oxygen had become enriched in the earth’s atmosphere…Much later, around 500 million years ago, the first green land plants settled on the banks of the waters and spread gradually across the continents.”

Lena Delta, Siberia. © Bernhard Edmaier

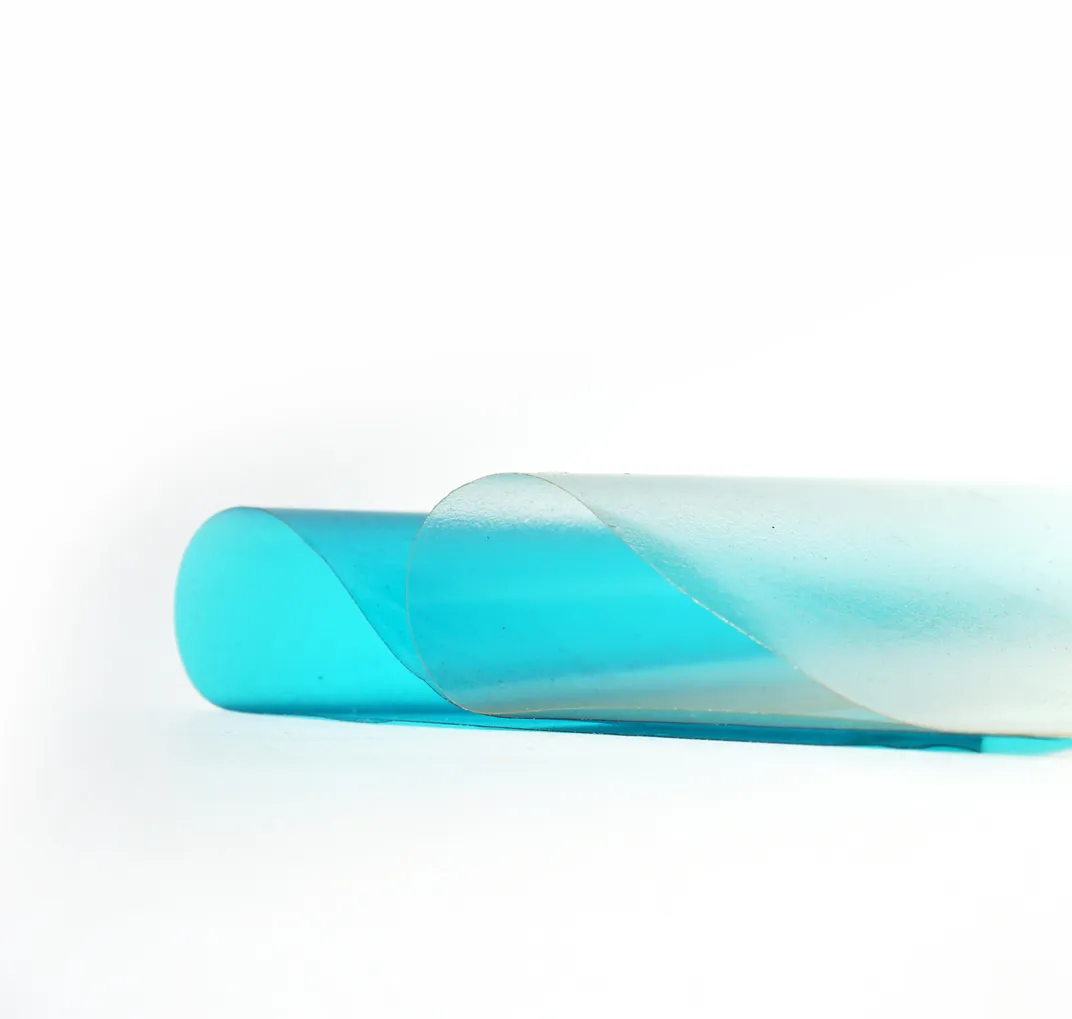

Edmaier thinks most humans have a very anthropocentric view of the world. “In our imagination, the Earth or Earth’s surface is something eternal or with very little changes. But the opposite is true. Infinite processes are continuously remodeling the surface and interior of the Earth. But only a few processes are directly observable,” he says. The photographer specifically chooses landscapes that have not yet been touched or altered by humans.

Mount Etna, Sicily, Italy. © Bernhard Edmaier

“Most of these spots are fragile, nature-created formations which, in the long run, will be unable to resist man’s unstoppable urge to exploit. They will alter and ultimately disappear,” says Edmaier. “So, I would be happy if at least some viewers of my images decide for themselves that the remaining intact natural landscapes are worth preserving.”

Karlinger Kees Glacier, Austria. © Bernhard Edmaier

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/28/48/2848155c-e307-42db-a1c1-60c1167d47f0/131_usa.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d8/93/d8934b5e-eb01-4b2f-87b5-c528ae4c0abb/bernard-ehrmaier-test-resized.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/57/db/57db7e93-3554-46ea-b474-f19528954000/prototype.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a6/53/a653ab80-f57a-4f72-9e3b-600a80b9d7c9/201706027-microneedle-patch.jpg)