The Secret Lives of Animals Caught on Camera

Photographs shot by camera traps set around the world are capturing wildlife behavior never before seen by humans

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/camera-traps-China-Snowleopard-631.jpg)

Great photography is about being in the right place at the right time. But to capture the most candid shots of wild animals, perhaps the right place to be is far away—out of sight, hearing and scent of them.

That’s the concept behind camera trapping, a niche of wildlife photography that has been around for nearly 120 years. It was invented by George Shiras, a one-term congressman working in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, who rigged a clunky camera with a baited trip wire. All types of animals—raccoons, porcupines and grizzly bears—tugged on the wire, which released the camera’s shutter, ignited a loud magnesium powder flash and snapped a portrait of the startled animal. Modern camera traps are digital and take photographs when an animal’s body heat registers on an infrared sensor or the animal crosses a motion-sensitive beam of light. To wildlife, says Roland Kays, a biologist at the New York State Museum, a camera trap is “just a piece of plastic on a tree. They don’t hear anything. There is nothing that they realize is going on.”

Traps from the Appalachian Trail to the Amazon rain forest to giant panda reserves in China have collected so much data that the challenge now is to efficiently organize and analyze it. To encourage sharing among researchers and with the public, the Smithsonian Institution recently unveiled Smithsonian WILD, a portal to more than 200,000 camera-trap photographs from around the world.

In their simplest application, camera traps let biologists know what species inhabit a given area. “For many smaller species it is difficult to tell from track or feces,” says William McShea, a research ecologist with the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Kays’ partner in launching Smithsonian WILD. “This provides ‘proof’ that a specific species was at a specific place on a specific date.” The evidence becomes even more valuable when the species photographed is elusive, threatened or even previously unknown. The only evidence for a tree-dwelling relative of the mongoose called a Lowe’s servaline genet was a pelt that was collected in 1932—until 2000, when one traipsed in front of a camera trap in Tanzania. The furry rump of a wolverine, perhaps the only one living in California, appeared in a photograph taken in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in 2008. And a strange, long-snouted insectivore, also in Tanzania, wandered in front of a lens in 2005; scientists eventually captured live specimens and named the newfound species the gray-faced sengi, a kind of elephant shrew.

To estimate the size of an endangered population in the wild, researchers have traditionally used a capture-recapture method, which entails sedating animals, tagging them, releasing them and then recording how many tagged animals are recaptured. For animals that have distinctive markings, such as tigers, “capturing” and “recapturing” can be done less invasively, with camera traps. Photographs of the rare giant sable antelope in Angola inspired a team of scientists to start a breeding program. The cameras can also confirm the success of a conservation effort: In Florida in the mid-1990s, panthers and other wildlife were photographed using highway underpasses that had been built to protect the cats from being hit by cars.

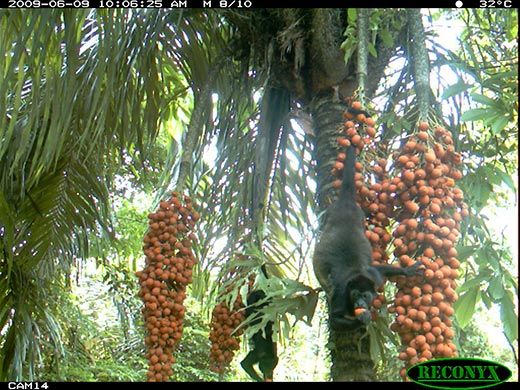

Traps often snap sequences of photographs that can be stitched together to provide insight into complex behaviors. The view is not always glamorous. Traps have caught two white-lipped peccary pigs mating in Peru and golden snub-nosed monkeys urinating on cameras in China. Kays has seen an ocelot curl up for a nap and a vampire bat feed on a tapir’s leg. “If you run enough cameras,” Kays says, “you capture some cool things about what animals do when there is not a person there watching them.”

Researchers often design studies with this in mind. Scientists in Florida and Georgia mounted video cameras near nests of northern bobwhite quail to find out which species were preying on eggs and chicks. They were surprised to find armadillos among the bandits. Remote cameras stationed outside black bear dens in the Allegheny Mountains of western Virginia revealed that hibernating bears leave their dens and their cubs frequently during the winter months. “People have been observing bear dens for years and never documented this phenomenon,” says ecologist Andrew Bridges of the Institute for Wildlife Studies, who led the study.

In one photograph on Smithsonian WILD, a jaguar, head hanging and eyes locked on a camera, closes in. In another, an African buffalo’s mug is so close to the lens that you can see its wet nose glisten. The encounters are dramatic, even entertaining. “We run out and check the camera trap, bring the pictures back, look at them on a computer and get really excited,” says Kays. “We want to share some of that with the public and let them see.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)